Ian Trowell is a PhD candidate in the School of Architecture in the University of Sheffield, working as part of a wider project within the White Rose College of Arts and Humanities. His recent publications include research on Northern post-punk identities in the journal Popular Music History and a critical analysis of photography in the early punk scenes in the journal Punk & Post-Punk.

Abstract

The fairground offers a complex soundscape that incorporates both music and non-music in a variety of patterns, frequently pushing towards multiple manifestations of noise through modes of distortion, cacophonous overlay and sheer excess. After proposing a reading of the totality of the soundscape of the fairground, this chapter argues that music is an integral part of the fair, and is listened to in a variety of collective rituals in a heightened state of anticipation. The chapter focuses on the Waltzer ride, and follows the work of a particular ride called Atmosphere Creator, which prioritises modern dance music within its armoury of attractions and effects. An extended film clip of the ride in action is included in the chapter, and a key part of my analysis involves a detailed study of this clip, identifying various actors and their relationships, choreographed through the diegetic soundtrack. I then take the music of the fairground and the Atmosphere Creator as a specific genre and look at its social uses outside of the fairground. The sound of the fairground and the crossover between music types and subcultures is a subject that has avoided academic research or serious documentation, and this chapter is a start to redress that absence.

Introduction

King’s Lynn Mart Fair traditionally marked the start of the season for travelling fairs in the UK,1 setting out amusements on the Tuesday Market Place from 14 February for a period of two weekends. In recent years, the notion of an end and start to the season has been somewhat eradicated with the preponderance of Christmas and New Year fairs, while the claims of King’s Lynn to be the season opener have diminished under the onslaught of newly implemented Valentines fairs up and down the UK. However, the Mart Fair maintains a sense of importance, including an official opening ceremony and a thickened sense of belonging and history in this economically struggling and isolated market town and seaport.2 In the run up to the fair, talk around the town in the coffee shops and meeting places becomes predicated on the encroaching event. On numerous occasions I have heard reference to the prevailing climatic conditions being ‘fair weather’, such that the vicissitudes and disobedience of the British weather temporarily bend to the will of the Mart Fair. Part of the tradition of this fair is ‘half-price Monday’, or ‘children’s day’, when all attractions run for the day at a heavily discounted price. While this is emblazoned on the posters around the town, it is also engrained into the memories and habits of the populace; the Monday is a busy day, insanely busy.

The content and organisation of the Mart is typical for a twenty-first century UK fair. The rides and stalls are enclosed in the bounded square, overlooked by historical Georgian buildings, encompassing hotels, businesses and the Victorian Corn Exchange Theatre (see Figure 1). The principal element of the fair is the large ride, split roughly between white-knuckle thrill rides and family rides, while a number of smaller children’s rides, round stalls, side stalls and food joints complete the topography. The days of the fair being tightly bounded by an assortment of bawdy and eye-catching shows slowly fizzled out during the latter half of the last century. The magical nature of the fair does, however, remain. The attractions arrive (and depart) under the cloak of darkness and fit together ‘just-so’. Mechanical arms studded with lights extend out and rotate in all directions, creating what appears to be a functional whole. As the fairground rides begin to resemble complex machines-in-themselves, as opposed to simulative devices, the fairground becomes one huge and complex device or contraption.

At the heart of the fair stands a ride that carries its own tradition within the wider tradition of the Mart. Albert Evans’ Waltzer has been attending this event for decades, and since the 1980s has provided the endearing musical experience for the Mart. February 2016 was typically cold, and the ice wind was whipping in from the Wash and River Great Ouse, finding its way between the sealed buildings around the square and the seemingly sealed fair within the square. Evans’ Waltzer – named ‘Atmosphere Creator’ – was thronged with a crowd of teenagers, working to full sensory effect.

The front canopy is studded with colour-changing LED lights and has the strapline ‘Prepared for Peace Ready for War’ picked out in bright letters.3 Underneath the canopy are fitted a bank of ten DMX sharpy lights, prowling and projecting beams across the square and into the night sky, illuminating the high-tech checker-plate steps (see Figure 2). Inside the ride a further ten beams pick out the chaotic motions of the cars and riders. The interior is finished in matt black, allowing the lights, strobes and smoke machines to have maximum impact. Sound is amplified through Martin Audio speakers mounted on uprights, while bass speakers lie underneath the ride itself, creating an earth-shaking sonic experience. The whole ensemble has been carefully assembled to a high standard over many years, and the operator is always looking for something new, something better, something different from the other Waltzer operators.

The music played is a relentless happy hardcore merged into new styles such as bounce, donk and power-stomp. The operator, Albert John, oversees proceedings from the centre paybox, interjecting on the microphone to direct customers to empty cars in the brief moments when the ride is stationary, or spieling the patter of the Waltzer operator with demands of ‘I want to hear you scream’ or ‘D’ya wanna go faster?’ Using the modern method of digitally sourced and delivered music, the mix segues into a frantic track peppered with bass and breakbeats around the clearly enunciated sample ‘Who is Elvis?’ For a brief moment over 50 years of pop culture has progressed to eat its own tail, and it is clearly loving every minute of it.

Fairs and their soundscape

In any week there are up to 150 travelling fairs set up across the UK. Each fair may last anything from a single day to a couple of weeks. The fair may occupy a dedicated grassed site such as a common or park, a discrete plot of concrete within the urban enclave such as a car park, or in the best cases it will stretch out in a rhizomatic fashion within the urban space, refashioning dead zones and interstices of the urban epidermis with a new thrill of lights, sounds, smells and anticipation. The perceivable acoustic environment, or soundscape,4 of the fair is complex and seriously understudied. It carries an understanding across time in a diachronic fashion (the cacophony of the event was equally so when contributed to by steam- powered organs as it is today with amplified pop music),5 while also evolving with regard to aspects and essences in a synchronic fashion.

The soundscape of the fair breaks down into three aspects: a collection of elements (sound sources or essences), a collection of effects and distortions accompanying the elements, and a collection of associated synesthetic measures. The elements of the fair include the music itself played on the major rides,6 the noise of the mechanical operation of the ride itself, the screams and shouts of the riders and onlookers, the voice of the showman, and (in the modern era) a panoply of amplified samples. The effects accompanying the sounds include a competitive layering to create a cacophony, the experience of listening to music while in motion (Doppler Effect) and a frenzied collective listening of music. Synesthetic measures include the artwork associated with a fairground ride through the development of iconographic and figurative designs corresponding with music genres, and also a synchronising of the movement of the fairground ride with the music to stimulate an extreme bodily feeling of music.7

A fairground such as King’s Lynn Mart, set out as an uninterrupted and tightly bounded whole, presents a topological paradox. A ride such as the Waltzer will form its own micro-environment in a monadological fashion, with the space between the fairground whole and the iterative whole of the individual fairground ride navigated by illusionistic patterns of circular structures with repeating motifs and designs. The sound of the fairground is concentrated within the outermost whole (the fairground itself) but escapes its boundaries by sheer volume and cacophony. The fairground can be heard (and seen, and smelt) before you enter into its realm. At the level of individual fairground rides we see a mix of acoustic strategies with speakers from some rides positioned outward facing, such that sound is centrifugally amplified into the general fairground space, and inward facing, such that sound is centripetally amplified into the enclosed space of the specific ride. It is clear that the soundscape of the fair is both complex and heteroclite. However, in turning again to Albert Evans’ Waltzer, I wish to diachronically map out a key sound experience of the fairground using examples of element, effect and synaesthesia.

The Waltzer

The Waltzer emerged on the UK fairground in 1930 as part of a new generation of lighter and faster roundabouts, sharing space with a very similar ride known as the Ark Speedway.8 Both of these rides followed from an architectural design tradition involving a standing, circular structure housing a rotating and undulating set of platforms which, in turn, supported either a set of wooden mounts in the case of the Ark Speedway (initially in the form of caricatured animals and then in the form of motorcycles) or revolving metal tubs seating up to six riders in the case of the Waltzer.9 The desired lightness of these rides, to facilitate quick transportation, build-up and pull-down, meant that decorative aspects shifted from an emphasis on carved ornamentation in excess of the essential structure, to painted flat surfaces inherent to the essential structure.10 As Ian Starsmore explains regarding fairground rides in general: ‘a mechanical ride is something which does not readily fall into any one category: art, construction, transport, all three enter into the equation’.11

Initially, both ride types were part of the simulative tradition, with the Ark Speedway clearly mimicking the thrill of riding a fast motorcycle, while the Waltzer referred to the swirling movements of a dance. The Ark Speedway took DeNora’s idea of entrainment even further with the simulation of motorcyles, finding resonance with Willis’ research into biker culture and the linking between music, rhythm and riding a motorcycle.12 The artwork developed for either ride cleverly reflected these simulative purposes, with speed, thrills and bravery alluded to regarding the decoration of the Ark Speedway, and twisting, interlocking patterns associated with the Waltzer. This artwork served a dual purpose, both enforcing the illusionistic and disorienting whole of the fairground through its familiarity and repetition, and signalling the punter towards an individually marked-out ride through nuanced differences of evolving modernity and novelty. As Stephen Walker shows, this artwork was fast and furious, applied, abused and then recommenced when fashion or fatigue necessitated.13

Both the Ark Speedway and Waltzer were social rides with an enclosed space, and benefited from the post-war boom in teenage subcultures and new music scenes. The Ark Speedway and Waltzer became the space to experience new music in both a defamiliarised space and also without the restrictions placed upon the young (age barriers, money, parental governance). As prominent 1960s artist Dudley Edwards comments: ‘When Rock and Roll first came on the scene in the fifties the ONLY place you could hear Little Richard, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran at loud decibel levels was at the fairground and we would all dance around the edge of the Waltzers’.14 One sound effect associated with old Ark Speedways and Waltzers would be a slowing down of records by about 6 or 7 rpm when the showmen applied the ‘knife’ to start the motion, the generator effectively being diverted from powering the audio equipment to starting the ride.

The synaesthetic nature of each ride had a strong differential, and this seemed to correlate with the experiencing of the music through the aforementioned mode of entrainment. The Ark Speedway evolved a symbiotic relationship with the music through both its rhythm and strong narrative element, while the Waltzer tended to take second place. Rock and Roll and subsequent genres through to Northern Soul told of the thrills and spills of adventures in teenage love, and of the joys of discovering music and all-night dancing. The musical structure was a steady beat, with eventual crescendos acted out through clapping (or stamping) actions. Showman David Wallis recalls an incident on a fair when the crowds were feverishly and collectively stamping their feet to the 1964 hit record Bits and Pieces by the Dave Clark Five with such a force that the wooden gratings around the ride were broken through.15 The Ark Speedway offered a journey with a beginning and an end, corresponding to the forward narrative of many of the lyrics of the time. Importantly, the Ark Speedway combined the social with the individual. Each rider had to compose themself on the ride and was responsible for maintaining a pose within the strictures of the rotating and undulating forces of the ride. This packaged mode of ‘listening-through-acting-out-through-riding’ continued with classic records such as the Shangri-Las’ Leader of the Pack (charting on release in 1964 but also charting on re-release in 1972 and 1976), which referenced motorbikes, through to funk anthems such as Brass Construction’s Movin’.

1977 proves a key musical year on the fairground, whereby the dominance of the Ark Speedway is toppled by the Waltzer under the regime of the disco genre expanding its limits. It is instructive to take three instrumental disco tracks that were all huge hits on the fairground to highlight the emergence of the ‘Waltzer sound’: the Rah Band’s The Crunch, Space’s Magic Fly and the Donna Summer classic I Feel Love. The first of these tracks conforms to the clear rhythmic structure of preceding musical styles associated with the fairground, The Crunch borrowing heavily from glam and glitter beat. Magic Fly almost achieves something else but seems to rein itself in towards maintaining a regular rhythmic structure – you can still clap your hands and stomp your feet to this record. However, Donna Summer’s I Feel Love – her second hit collaboration with futuristic producer Giorgio Moroder – pushed the envelope towards a breathless and frantic polyrhythmic experience. Chambers describes the polyrhythmic method to ‘bend, tease and subvert the regularity of the beat’ such that ‘attention is directed to the interior of the musical experience … drawn to an insistent now’.16 He later generalises disco to have a musical quality such that each track has ‘no beginning or end, just an ever-present ‘now’’.17 My suggestion here is that it would be Summer’s I Feel Love that introduced a significant polyrhythmic dimension. This would signal and soundtrack a move away from the Ark Speedway to the Waltzer ride, and set the trend for high-energy frenetic electronic music. In addition, while the Ark Speedway demands an individual effort to stay composed, the Waltzer is truly social with microcosmic social scenes within each car and the sociality of the whole ride. The individual here gives themselves over to the ride; you are enclosed within the structure effectively immobilised backwards onto the cushioned curvature of the car (see Figures 3 and 4).

Fairground music as genre post Second Summer of Love

The Second Summer of Love is usually associated with the year 1988 and the explosion of rave culture as both a genre of music and a new mode of collective engagement with the music. An amalgam of dance music styles from various cities (Chicago, Detroit, New York, London) or scenes of eclectic and experimental partying (the Balearic scene) birthed a full-on new sound that was both distinct and evolving (acid house, breakbeat, techno, and so on). Collective consumption of the music switched to large raves and the resistant free party scene, with subcultural accoutrements including designer drugs, clothing and argot. The fairground embraced this pulsating and energising sound after a decade in the 1980s when music had fractured into various pop scenes. As raves became licensed and larger in scale, fairgrounds began to appear on these sites, augmenting the link between the music and the fairground.

The sub-genres of music that flourished after the initial impetus of rave were swift and complex, reacting against each other as scenes and genres bifurcated in pursuit of either distinction or the continual quest to keep the frantic vibe and energy of the music. The Waltzer sound became predominantly associated with the rave genre, and followed the styles of music that attempted to keep the spirit of rave alive and kicking with genres such as happy hardcore. This music eschewed technical wizardry and atmospheric nuances and structure, instead opting for a fast assault on the ears through intense breakbeats, ‘helium’ vocals pitched high and fast, and anthemic breakdowns and peaks designed to whip listeners in to a frenzy. It was, and remains, a genre that is looked down upon by music aficionados.

The niche genre around hardcore techno, evolving forwards while forever revisiting its own past to create a rhizomatic array of all possible nuances, thrives outside of the mainstream dance music cultures. Small scenes cluster around specific venues in the North of England and Scotland, with specialist genres such as ‘bounce’ and ‘donk’ attaching themselves to dedicated clubs and production crews in cities.18 With an absence of regular club nights, the collective listening to scenes such as donk would be fulfilled through sitting in cars19 or visiting the fairground. In return, the tradition of fairground enthusiasm, which started as a loose network of societies to discuss and share memories and develop amateur research into fairground history migrated into a hybrid mix of traditional fairground fans and hardcore music fans. Discussion hosted on fairground internet forums, considered by Henry Jenkins as ‘epistemophilia’,20 moved from shared expertise on the nuts and bolts of fairground machinery towards dissecting the music heard on hosted video clips of Waltzer rides in action. This dialogue from the All the Fun of the Fair website discussing a clip of Percival’s Waltzer provides a good example:

Poster 1: Scouse house/bounce is the name of the genre. It started in the North West and was most popular around 2000 – 2009, it’s taken a nose dive now because the people that used to like it prefer the electro house these days. It’s had a bit of bad reputation for being not very musically original, personally I love it, but from a production point of view it was very much ‘bedroom production’ hence the term ‘put a donk on it’ – any track sounds good with a banging donk!

Poster 2: At around 2 mins 54 in that video he swaps over to Powerstomp – now this is a relatively new genre of hardcore music pioneered by DJ Kurt and Joey Riot under the Lethal Theory label. It’s very high energy 175bpm hardcore music with a much punchier kick and its becoming more popular these days both in the UK and abroad. The track he plays is Joey Riot & Chaos – Get Down. Hardstyle is completely different, it’s the Dutch version of hard dance at 150bpm (bounce house is 170bpm ish), different kick drum and style. More popular than either of the above genres too.

Evolution of Atmosphere Creator

The Atmosphere Creator began life in 1953, as a brand-new Waltzer from the Scottish company Maxwell for the Yorkshire showman John Ling.21 Its initial decoration was of the classic style of the 1950s Waltzer, featuring an Odeon patterning and architecture of mock structure templates in ascending repetition. Typically, the ride did not use decoration to appeal to a particular music-oriented market, and had a design that celebrated the presence and grace of the ride, the strapline on the canopy reading ‘The Latest New World Thriller’. It maintained this decoration for around two decades, moving on to the stewardship of Albert Evans, who married John Ling’s daughter Joan in 1968. By the early 1980s Albert John Evans, the son of Joan and Albert, was a teenager taking a strong interest in the family’s Waltzer. It was at this point that the ride underwent a radical transformation, adopting an all-over artwork featuring an intense pop melange from the skilled brush of artist Paul Wright. In many ways Paul’s work on the ride echoed back towards the early 1950s figurative artwork featuring Rock and Roll stars such as Bill Hailey and Elvis Presley, a style and approach that had been all but forgotten. Paul sourced Smash Hits and NME to gather portraits of artists such as Yazoo, The Clash, Elvis Costello, Billy Idol, Ian Dury, Fun Boy Three, Blondie, Madness and numerous New Romantic bands (see Figure 5).

The strapline on the canopy was re-lettered to ‘The World’s Latest Disco Waltzer on Tour’ and the key image on the front of the ride was Donna Summer extending her arms wide to draw you into the interior (see Figure 6).

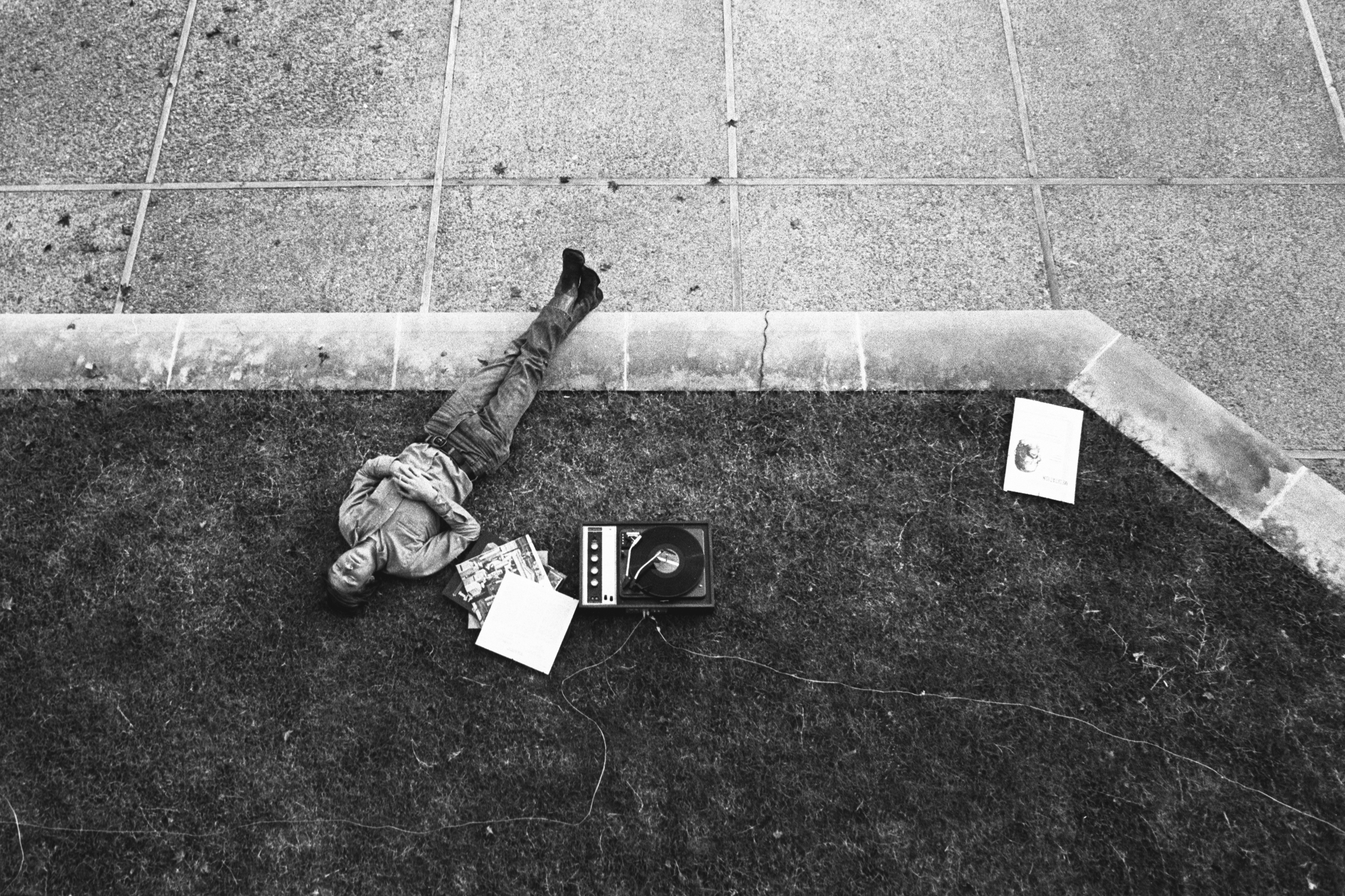

Albert John confirms the importance of Donna Summer’s I Feel Love as a composition that broke free from the existing structures of disco music and, in turn, created the perfect soundtrack for the Waltzer experience.22 From this point on Albert John, as a teenager, began seeking out innovative music from the wilderness years of the mid-1980s, looking for the polyrhythmic structures that would make his ride stand out from the rest as a fusion of sound, movement and machinery. He took his copy of I Feel Love to the record shops on his travels, asking to be provided with tracks that could match it, gathering the sporadic music from that decade that pushed the limits: Grandmaster Flash’s White Lines (1983), Harold Faltermeyer’s Axel F (1985) and New Order’s Blue Monday (1983).

Eventually he developed a following for the Waltzer such that it was remembered and eagerly anticipated on the family’s run of fairs. By the time of the Second Summer of Love (1988) and the sudden growth of the rave scene, Albert John was keyed in to the music he wanted for the ride and the record dealers that could supply it (principally places like Eastern Bloc in Manchester). The Atmosphere Creator quickly doubled as a mobile venue for the latest music and scene, allowing people to experience it with lights, smoke and intense movement. The ride underwent a final transformation in 1989 with the early 80s popstars giving way to science fiction and club imagery. Structural changes were made and innovative aspects such as lights embedded within the steps were added.

The film clip shows the Atmosphere Creator at work during Boston May Fair 2011, a time when hardcore and rave music would be hard to find in the regular offers of entertainment in any city. But here on the fairground the music is still going strong and it is possible to observe various practices on the film clip. It is busy and Albert John is keen to maximise business. His microphone patter at the start of the clip is blatantly towards economic interests within the frenzy of the occasion: ‘All these front cars, let’s go’, ‘Don’t forget it’s only £2.00, if you need some more keep your seats’, ‘Hurry up girls, get in’, ‘Three or more in a car please, come on’. In the space of less than a minute, in what looks like an accelerated game of musical chairs set to industrial strength music, the ride is ready to go again with a full complement of customers. As the speed picks up Albert John sets the tempo and anticipation with a shout of ‘Hold tight’, only to have to quickly admonish an over eager customer with a command of ‘No, don’t come over the hand-rail’.23 The ride cycle is short (around two minutes), as clearly the crowd are desperate to take centre stage and experience the ride (or experience the music through the ride). As the camera pulls away from this first complete cycle of business and the next cycle commences, we see flame effects shooting vertically from the canopy and the interior of the ride shrouded in dry ice. Immediately Albert John is forced into remonstrative mode as he spots a rider trying to stand up: ‘Sit down, idiot, sit down. You will come out if you stand up, this is fast’.

Stephen Walker, looking at the complexity and fluidity of the territorial inside and outside of the fair, considers the Waltzer at Loughborough Fair as an eventual zone or region of its own autonomy within the fair itself. He writes:

As the evening wears on the ride closes in on itself, closes itself off from its surroundings while attracting a predominantly under-18 audience with the promise (and delivery) of pseudo-transgressive hardcore techno music and a rave environment that they would not otherwise (well, legally, or with parental consent) be able to access.24

As we see from the film clip, the atmosphere that the ride creates pushes behaviour towards frenzy and transgression, daredevil performativity from young males, and the operator must be eagle-eyed. Albert John switches between pushing the atmosphere up by orchestrating acts such as putting hands in the air and screaming, and having to watch the action unfold.

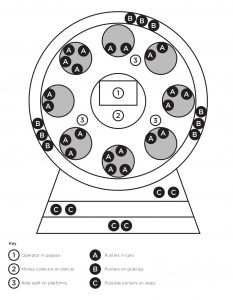

The sequence between 7-20 and 8-00 minutes is shot from a fixed viewpoint and this allows us to see the operation in full effect with the gaff lads set out as a circular phalanx spinning the cars. There is a small amount of rushed dialogue spoken by Albert John in this sequence, where he appears to be addressing the gaff lads with a command to spin cars 2 and 8, making sure that each customer gets the maximum pleasure and experience from the short ride, in the hope that they will ride again (and again). Using the method developed by Wendy Fonarow25 for mapping ‘zones of participation’ at indie gigs, and applied further by Geoff Pearson26 to study British football crowds within the stadium, Figure 7 shows the layout of the Waltzer from the twin perspectives of the operator and his staff and the punters. Each mode of punter determined by their spatial positioning necessitates a certain relationship with the operator: those in the cars are customers who require the best experience, those standing on the gratings are quasi-customers who require close control, while those loitering on the steps are potential customers who require encouragement. Albert John can be heard around the 10-05 mark appealing to the group of people on the steps, urging them to come ‘Up the steps’.

Music, and the listening of music in a collective fashion, forms the heart of this operation, working at a new intensity of expressive entrainment beyond simply clapping hands or stamping feet. The raucous and energising nature of the music selected by Albert John functions at various levels: it provides an added reason for going on the ride itself for the group labelled A (and so complements the economic imperative of the operator), it encourages transgressions of behaviour through hyperbolic performance both on the ride and around the ride (group A admonished for standing in the cars, group B admonished for standing on the barriers), for which the operator has to keep a sharp eye out, and it attracts people to the ride – initially to the front steps (group C) and eventually up onto the ride itself (group B). Some of those on the steps and standing on the gratings need to be converted to riders (group A), but the operator knows that a crowd on the fair attracts more people. There is a complex balance to be kept, and the economic weighting of that balance is short-circuited if the ride forms simply a gathering place to listen to music in what might be a ‘traditional’ fashion of downgraded interactivity.

Club spaces and fairgrounds

The collective or social enjoyment of dance music evolved through venues and nightclubs catering for the specific scenes that flourished in post-war British popular culture. Research in this area tends to focus on the structure of the scenes and the testimony of participants, rather than structural, technical and aesthetic nature of the building and space itself.27 Certainly during the mid-1970s under the regime of Northern Soul venues were spartan and functional, with an emphasis on providing a surface for expressive, acrobatic dancing. Again, the nature of this subcultural scene with regard to its sheer dedication and transgressive vectors prioritises a literature drawn from, and deconstructing, social participation.28 The Northern Soul scene crossed over with the disco scene during the 1970s, and here an emphasis on a structured atmospheric was evident with considered effects through multiple forms of lighting (flashing sequences, lasers, light panels in structures including the dancefloor itself), smoke machines, mirrors and advanced sound-systems. While fairgrounds are said to provide a version of a nightclub space, it is important to separate out between the provision of an opportunity for those not able to go to a nightclub and the simple copying of a nightclub, which would suggest a vector running from the nightclub to the fairground ride.29

The modern (post-1988) movement of accelerated dance culture manifested initially in raves and then in new clubs (and designated super-clubs) is analysed at a spatial level by Ben Malbon, though again there is an emphasis on the social practices afforded by the space of the nightclub with regard to a tribal identification and the claiming of a space.30 Malbon extends this analysis of the dance music club away from the spatial-in-itself and towards the affordance of the spatial, to draw on ideas developed by both Maffesoli, proposing identification (against identity) and unicity (against unity), and Canetti, regarding exstasis and the loss of self, in the search for ‘spaces and experiences of identification or affective gatherings’.31 An earlier key work by Thornton provides a similar mapping between the rave/club and the fair at both a spatial level and social practice level: ‘Clubs offer other-worldly environments in which to escape; they act as interior havens with such presence that the dancers forget local time and place … Clubs achieve these effects with loud music, distracting interior design and lighting effects’.32 These interior accoutrements and their associated affects can be mapped over to a Waltzer such as the Atmosphere Creator. Thornton continues: ‘Classically, they have long winding corridors punctuated by a series of thresholds which separate inside from outside, private from public, the dictates of dance abandon from the routines of school, work and parental home’. While this last statement possibly conflates the singular room (and its affordances) and the enclosed network of rooms, it is possible to map this onto the fairground whole and its interior spaces (such as the Waltzer). The work of Malbon and Thornton concerning the spatial arrangements of the club is suggestive rather than prescriptive and exhaustive, though I include it here as a preliminary dialogue between the fairground and the club.

Conclusion

Listening to music on the fairground is a fully embodied and polysensory experience, taking DeNora’s theory of entrainment into new realms of energetic performance. I have introduced the total soundscape of the fairground and this forms one of the sensory excesses that define the experience. The purpose of this chapter is to focus on the particularities of the fairground sound, with specific regard to the ride called the Waltzer. As I pull apart the sound of the Waltzer a synergetic shift is revealed; the sound of the fairground as listened to through the distinct performative arena of the Waltzer becomes a fairground sound in itself. Precise genres such as donk and bounce flourish and are appreciated through evolving collective practices on the ride.

Elsewhere, the spaces between the fairground rides, the ‘ground’ of the fairground, are cacophonous in the extreme as rides compete with each other to offer the best sound and experience. I would further argue that this cacophony is not just heard, it is engaged as meaningful. It is listened to in the way that discernible music is listened to on individual rides. Such a cacophony forms a natural fit with the fairground, and it stands out in an age when a joyous heteroglossia is being pushed onto the margins of social life (old-fashioned markets being replaced by modern shopping malls is a key case in point).

Fairground art’s natural parallel in the art canon is the school of Pop Art, with ideas and influences flowing both ways, though seldom acknowledged in the vast swathes of literature on this genre. Hal Foster has recently authored another collection of considered thoughts on Pop Art and turns to Andy Warhol’s 1963 work Elvis Six Times. In this picture we see Presley as a gunslinger fading from view as we scan from left to right, a process Foster describes as ‘deterioration through seriality’.33 Other writers link Warhol’s depictive method of slow fade of expired celebrities to his obsession with fame and death, and his own insecurities that plagued his life. Seriality of figurative (and non-figurative) art was part and parcel of the fairground painter who illustrated rounding boards and shutters for circular rides and stalls. Furthermore, fading of the art generally followed production, as fairground art is unacknowledged as part of the valuing system attributed to Pop Art and fairground art is set out exposed to the elements for the public to enjoy. Elvis, and all the depicted stars, fade, many times. They then get painted over. Over 50 years later Albert John Evans entertains a crowd of immersed and exhilarated teenagers on his Atmosphere Creator Waltzer. In the midst of an array of lights and smokes, donk noises and breakbeats, he plays the sample Who is Elvis?

Select bibliography

Braithwaite, David. Fairground Architecture. London: Hugh Evelyn, 1968.

Chambers, Iain. Urban Rhythms: Pop Music and Popular Culture. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1985.

DeNora, Tia. Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 2000.

Fonarow, Wendy. Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music. Middletown: Weslayan University Press, 2006.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Soundscape: The Tuning of the World. Rochester VT: Destiny Books, 1994.

Starsmore, Ian. English Fairs. London: Thames & Hudson, 1975.

Thornton, Sarah. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. London: Polity, 1995.

Weedon, Geoff and Ward, Richard. Fairground Art. London: White Mouse Editions, 1981.

You must be logged in to post a comment.