Simon Brown is a Research Associate at the Royal College of Music working on the Listening Experience Database (LED) project, and an Associate Lecturer with The Open University.

Abstract

Historical evidence of listening to music by practitioners can often provide us with an unusual level of detail about their experience. But in what form does this data usually exist? How could we set about studying the evidence and what insights might it provide? This chapter focuses on the type of methodology that might be used for the systematic study of the listening experiences of a single practitioner, with a view to how this could be applied to a larger dataset. It relies upon the facilities of the Listening Experience Database (LED) and attempts to illustrate what a tool like this has to offer.

The chapter will draw extensively on the listening experiences of Benjamin Britten between the years 1928 and 1938. This is the only period of his life during which Britten kept a daily journal. As such, his listening experiences are mentioned in almost every entry. John Evans noted in the preface to his 2009 published edition that:

the entries grow in length, complexity and private reflection; intimate thoughts were committed to a succession of pocket and desk diaries, [during] a period of self-reflection.1

After 1938 Britten’s only first-hand accounts of his listening experiences are available through his letters. His diaries therefore provide a unique and valuable insight into the unsolicited testimony of a practitioner.

Introduction

The types of sources that contain historical evidence of listening practices include: personal correspondence such as letters, diaries and memoirs; published books and articles such as biographies and autobiographies (particularly examples of travel and life writing); journalism; oral evidence; official papers and works of reference, to name but a few. But what form does data about listening usually take? It is often the case that the type of evidence does not always reveal what we might have initially imagined or hoped (for example, precisely how the listener felt about, or reacted to, a particular piece of music). Instead, the individual pieces of evidence are often casual comments, which contain contextual information pertaining to the experience, such as the repertoire, performers, location, date and times, and so on. Given the often dispersed and varied nature of this evidence, its analysis can be difficult and cumbersome. This chapter sets out to demonstrate how disparate pieces of evidence relating to the listening experiences of Benjamin Britten (1913–76) can be analysed by means of their extraction from a database, providing a more coherent picture than might otherwise be the case. The claim here is not that this study would be impossible in the absence of such means. Rather, the study may act as a pilot, showing how this technique might be applicable to a much larger and more unwieldy body of evidence.

The peripheral data

In the listening experiences of practitioners it is perhaps not surprising that information about the music and performers is often described in detail. This is certainly true for Britten, who often names the performers and repertoire as a matter of course throughout his diaries. In addition, Britten recorded much contextual data, and for this study all of these details have been entered into LED.

The data entry form on LED has been designed not only to capture the written testimony of the listener and the bibliographical details of how the evidence can be traced, but also the ‘peripheral data’ of each experience. By peripheral I mean the contextual evidence that is often apparent either explicitly in the text (such as a specific piece of music or composer being mentioned), or implicitly (such as whether it was at a concert at a named venue, meaning that it is safe to assume that the experience occurred indoors, in a public space and in the company of others).2 The fields on the data entry form facilitate the capture of details about the names of specific pieces of music, the composer(s), the performer(s), the instrumentation, the listening and performance environments, the locations, and how the music was transmitted. Labeling these details as ‘peripheral’ is not to suggest that they are inferior to the descriptive testimony of the experience, but merely that their significance is not always immediately apparent. On the contrary, in addition to drawing conclusions from the written testimony, it is the extraction of this peripheral data that can provide further insights into the listening habits and behaviours of an individual, or broader patterns across a range of listeners, locations, time periods and different types of music.

In addition to the standard browse and search facilities that are available via the LED homepage, the data can also be queried using the SPARQL language. This allows for more complex searches of LED, but also the facility to extract the data via the SPARQL endpoint of The Open University into a CSV (Comma Separated Values) file. Once in this format, the data can be interrogated further using standard software, such as Microsoft Excel, in order to examine it more closely and extract more meaningful results. An example of the SPARQL query that was used to extract all of the entries in LED that have Britten as a listener can be seen in Figure 1.3

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

PREFIX dbr: <http://dbpedia.org/resource/> PREFIX event: <http://purl.org/NET/c4dm/event.owl#> PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> PREFIX owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#> PREFIX rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> PREFIX rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> SELECT ?x ?text ?where ?when WHERE { ?x event:agent/(owl:sameAs|^owl:sameAs)? dbr:Benjamin_Britten ; foaf:page/rdf:value ?text OPTIONAL { ?x event:place ?where } OPTIONAL { ?x event:time/rdfs:label ?when } } |

The listening experiences of Benjamin Britten

Britten affords a fascinating insight into the listening experiences of a single practitioner. He lived during a period that witnessed the emergence of changes in technology that would profoundly affect listening habits and behaviours. There is also an abundance of evidence, a vast amount of which is readily available through his published diaries and letters.4 Britten frequently comments on listening to his own music as a composer, but also the effects of listening to others. His responses include different listening environments, such as during rehearsals, live at concerts, via radio broadcasts and on the gramophone player. Britten often records valuable details of the performers and the repertoire, in addition to his reaction to the performance, along with that of the audience.

Much of the current literature on Britten has naturally focused on his work as a composer. While we have learned much from the published material, in terms of his musical and cultural perspectives, there has been limited discussion about the specific effects of what Britten listened to, the ways in which he listened, and how this might have had an impact on his work as a practitioner. This chapter draws on Britten’s listening experiences between the years 1928 and 1938, the only period of his life during which he kept a daily journal, which has now been edited by John Evans.

Beginning in the composer’s fourteenth year, Britten’s diaries trace his development from Gresham’s School in Holt, North Norfolk, to his time studying at the Royal College of Music, through to his early career working for the General Post Office Film Unit, the Group Theatre and the BBC. By the end of 1938 Britten was on the brink of establishing an international career. His personal accounts enable us to explore a period of his life that would have a profound influence on him.

It is important to provide a word of caution here. Evans admits in the editorial notes to the published collection that not every word or, indeed, every entry of Britten’s diaries was replicated in the published edition. Evans explains that in Britten’s early accounts of his activities, mainly governed by his family circumstances or life at school, the diary entries are ‘very matter-of-fact in content, but the roll call of his many church-going, musical, sporting or bathing companions is always extraordinarily detailed’.5 Therefore, the evidence this chapter draws upon is only indicative of Britten’s practices and habits and does not, by any means, present the complete picture.

In reproducing Britten’s diary entries I have retained his spelling mistakes, choice of punctuation and grammar as they were in the published edition.6 In any piece of text, these types of idiosyncrasies can affect the meaning entirely and, as Evans noted, ‘they demonstrate the efforts he made to express himself more clearly, and the struggle he had to overcome his dyslexia-like battle with spelling’.7

Revealing the peripheral data

An example of his diary entry from 22 October 1932, written after Britten had attended a live performance of Mozart’s Piano Quartet in G minor K.478, reveals his sharp criticism of the performers and is indicative of his strengthening opinions, not just about how he considered Mozart ought to be performed – he was, of course, later to become a celebrated interpreter of Mozart himself – but of the standard of musicianship that he was growing to expect:

Meet Barb at 8.15 at Broadcasting House for concert (tickets from R.C.M.) in concert Hall at 8.30. English Ensemble – Kathleen Long (poor in spots). Marjorie Haywood (good) Rebecca Clark (musicianly but not inspired). May Mukle (poor tone).8

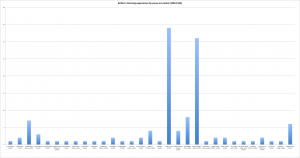

Aside from the criticisms directed at the performers, this type of experience reveals other aspects of the London concert scene during this time, such as the venues and performers. A review of several pieces of evidence like this provides us with a more accurate picture of where Britten most frequently listened to music during a specific period. Figure 2 shows Britten’s listening experiences by venue in London between late 1928 and early 1935. It reveals that most of his listening experiences occurred either at the Royal College of Music (RCM), where he was a student, or at the Queen’s Hall in Langham Place. The latter was London’s principal concert venue. It played host to The Proms between 1895 and 1941 before it was destroyed in the Blitz during the Second World War, but in the 1930s it had become the home for both the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra – both of which raised the standards of orchestral playing in London and attracted eminent musicians from across Europe and America (see Figure 3: Sir Edward Elgar and the London Symphony Orchestra on the platform of the Queen’s Hall in 1911, a photograph first published in The Musical Times the same year). The other most prominent venues that Britten frequented included Broadcasting House, the Royal Albert Hall and the Wigmore Hall, but most of these listening experiences occurred after 1930.

Britten moved to London in September 1930 to study at the RCM. As we might expect, this radically changed his listening habits in terms of the repertoire to which he was exposed and the standard of performance that he would witness. Britten had an uneasy relationship with the RCM and the reasons behind his feelings are complex, but they were likely to have been influenced in part, at least, by his attitude towards his fellow-students and the teaching staff such as John Ireland and Ralph Vaughan Williams, the latter of whom Britten considered to be the ‘old guard’ of English music. But as a young composer, Britten’s dissatisfaction with his time at College was understandable, and had much to do with the lack of performances that his own works received. As Paul Kildea noted in his recent biography of Britten:

by the time he left the RCM in July 1933, Britten had heard only two of his works in college concerts his Phantasy in F minor (1932) and Sinfonietta (1932), which had already received its premiere elsewhere.9

Britten himself later remarked about this period that without being able to listen to his own works ‘it was difficult to link notes and sounds’.10

A comparison of Kildea’s account with Britten’s diary entries confirms that there were only two performances of his own works at the RCM. The first was on 22 July 1932 and is perhaps surprisingly thin in detail, particularly since this was still such a rare occasion. Britten wrote:

Go to R.C.M. at 10.30, after finishing packing etc. to hear result of [sic] competition Cobbett prize – performance of my 5tet—bad—but I expected worse.11

The second was on 16 March 1933 and is equally sparse:

After dinner R.C.M. Chamber Concert at 8.15. Mum & Beth go. Bridges & Brosas also there. Beethoven C# min quart competently but dully played; an atrocious perf. of Delius Vl. Sonata no. 1. F. May plays. bit of Phantasy of Schuman [sic], & I conduct a show of my Sinfonietta which goes quite well.12

If we consider the number of experiences of listening to his own compositions that Britten documented during this short period, we can see that there were significantly more than this (see Table 1). Of course, not all of these would have been public engagements; some were private performances or listening experiences with friends and colleagues, such as on Cromwell Road in Kensington, where he lived between 1931 and 1933. The third listening experience at the RCM was a rehearsal and he would almost certainly have heard his own works by other means or on other occasions. But the fact that these are not reported in his diaries is quite striking, and it confirms that most experiences of his own music were outside of college.

Table 1: Britten’s listening experiences of his own works between 1928 and 1935

| Tite Street, London | 1 |

| Broadcasting House, London | 2 |

| Cromwell Road, London | 1 |

| London | 17 (30 inclusively) |

| Lowestoft | 2 |

| Mercury Theatre, London | 1 |

| Royal Academy of Music, London | 2 |

| Royal College of Music, London | 3 |

| St. George’s Hall, London | 1 |

| St. Martin’s Rectory, London | 1 |

| Teatro Comunale, Florence | 1 |

| Wigmore Hall, London | 1 |

| Total | 33 |

Limitations of the data

As with Figure 2, Table 1 reveals that there are a number of issues with certain aspects of the data. For instance, of the entries that have been submitted to LED at the time of writing this chapter, there are a significant number of listening experiences where the venue was either not listed or simply marked at city, borough or street level, such as ‘London’. This is not a fault at data entry level but merely reflects the level of detail in his diaries, highlighting the fact that we should be cautious when drawing conclusions from the data.

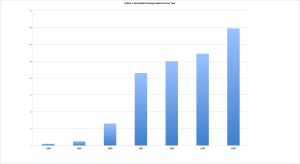

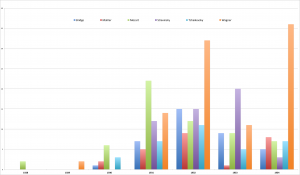

Indeed, a closer look at the data from his diary entries reveals the incompleteness of the picture. For instance, if we consider all the listening experiences that Britten documented in his diaries between 1928 and 1934, we see a dramatic increase in 1931 (see Figure 4). Looking more closely, however, the lack of data between 1928 and 1930 tells us more about how infrequently Britten wrote in his diary than about his listening habits. His diary begins at the start of the school term in late September 1928 and entries remain fairly sporadic until he attends the RCM in September 1930.

Figure 4 highlights how, having moved from boarding school at Gresham’s in Holt, Norfolk, to London in late 1930, Britten’s diary-writing habits became more assiduous as he attended college, and also the fact that he began to explore the London concert scene.

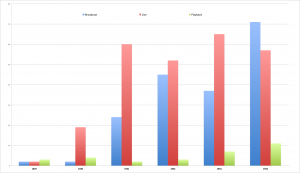

Figure 5 provides evidence of the different ways in which he listened to music, suggesting that, while his listening experiences of the gramophone fluctuated (with a slight increase overall during this period), they still remained relatively few at this time. By 1931 Britten would document, on average, his attendance at a minimum of one concert a week, while the number of reported instances of listening to music broadcast over the radio was growing steadily.

The limited number of experiences even by 1934 suggests a stark contrast to today’s listening habits; it appears that nearly all were either live or broadcast, compared to the very few that were heard over the gramophone. Or does it merely suggest that Britten rarely documented his experiences of listening to the gramophone as he deemed it less significant, compared to attending a live performance or listening to a radio broadcast? It is difficult to say with any certainty, but I would argue that the evidence suggests that Britten listened more frequently to the radio or to live performances than to the gramophone. His only access to a gramophone player during these early years was either the headmaster’s at Gresham’s School, or at family and friends’ houses that he would frequent, either in Lowestoft, Suffolk or London. Indeed, his father refused to have either a gramophone or, later, a radio in the house.13

Testing assumptions

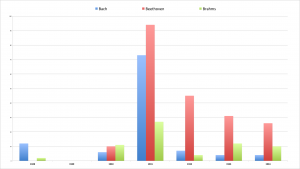

If we compare some of the assumptions from the current literature, we can see how these fare against the evidence that has been entered into LED. It has been widely observed14 that Britten’s early influences included ‘the three B’s’: Bach, Beethoven and Brahms – according to Carpenter’s biography, Britten’s mother hoped her son would become the fourth. In his diary of 13 November 1928, Britten wrote: ‘in my list of Composers …Beethoven is still first, and I think always will be, Bach or Brahms comes next, I don’t know which!’15

This is interesting as Britten’s diaries reveal very few – if any – listening experiences of Beethoven during this time, and only a handful of Bach and Brahms (see Figure 6). Therefore, might we assume that in the quotation from 13 November, Britten was referring to his enjoyment of playing their music rather than listening to it? This is unclear and, as I have already stated, he recorded very few listening experiences in his diaries during these early years, but after his move to London, the number of recorded experiences of listening to Bach and Beethoven were among the highest of all composers, which lends further credence to the claim that Britten preferred these composers at this time.

For his fourteenth birthday on 22 November 1927, he received the full score of Beethoven’s Fidelio and Britten later recalled that ‘it was a red letter day … between the ages of thirteen and sixteen I knew every note of Beethoven and Brahms’.16 Evans also noted in his published edition of Britten’s diaries that:

As time went by Britten’s admiration for Beethoven and Brahms waned; in the case of Brahms this happened remarkably quickly, largely because of the particular quality of his orchestration, which Britten grew to detest. …His admiration for the music of Bach, however, was constant, and he became a noted interpreter of the Brandenburg Concertos, the St John Passion and the Christmas Oratorio.17

And by 1928:

Britten had already developed a deep affection for Schubert’s chamber music …but as the years went by he was hailed as one of the finest Lieder accompanists of his generation, particularly noted for his performances of Schubert’s songs through […his] recital partnership with the tenor Peter Pears.18

Britten’s appreciation of Brahms gave way to a passion for Wagner, Schoenberg, Berg and Mahler. This would have been in part through the influence of the progressive musical tastes of his composition teacher and mentor, Frank Bridge, but also his exposure to the London concert scene during the 1930s. We can certainly begin to see elements of this trend in the 1930s by his accounts of what he was listening to. Figure 7 reveals that – aside from the three Bs – the composers that Britten most frequently wrote about in his diaries were Bridge, Mahler, Mozart, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky and Wagner. Despite the anomaly in 1933, Britten’s growing interest in Wagner during these early years in London is quite striking. Figure 7, taken in conjunction with Figure 6, suggests that Britten’s exposure to new repertoire significantly altered his tastes.

Of Schoenberg’s works, Britten only reported nine listening experiences between 1928 and 1934, and only one of Berg’s in 1933, but it is fair to assume that he would have been familiarising himself with the works of these composers via published copies of their scores. By comparing this data with other supporting evidence, we could begin to build a more accurate picture of who might have influenced him or where his musical interests were at specific stages throughout this period of his life.

By 1937, Britten’s diary entries were becoming more detailed and reflective than merely listing the performers or venues, as demonstrated in the following example from 30 October of that year:

Dinner at Isherwoods, & then I go to the Queen’s Hall with Basil Douglas to the Toscanini Brahms concert. Tragic Overture, & Requiem. Some how the efficientcy & skill [sic] inspiration of T. seems to make Brahms even thinner than ever. T. obviously sees what was at the back of B’s mind, & what he hadn’t the skill to put on paper.19

In addition to capturing the date and evidence of the listening experience, these slightly longer diary entries still contain details of the venue (the Queen’s Hall), with whom Britten attended the concert (Basil Douglas, who later became manager of the English Opera Group), who performed (Toscanini), and the repertoire that was performed (Brahms’ Tragic Overture Op. 81 and A German Requiem Op. 45). This particular entry is also a good example of Britten’s increasing criticism of Brahms, as well as his exposure to performers of international stature and his strengthening opinions as a composer.

Further details captured in LED are implicit within the evidence. For instance, in what type of listening environment the experience occurred; it is clear from the evidence that it was in the company of others, in a public space and indoors. The same can be captured about the performance environment, which might differ from where the music was being heard, particularly if the music was heard via a radio broadcast or over the gramophone. It appears from the Britten entries that have been captured in LED that the above example from October 1937 is typical of the type of listening environment that Britten usually experienced. The majority of his listening experiences were in the company of others (approximately 310) compared to being on his own (approximately 165); but the divide between whether they occurred in public (approximately 225) or private (approximately 260) is more evenly split; and virtually all of his experiences were indoors (approximately 475).20 Capturing this level of detail provides us with the opportunity to assess how listening habits might have evolved, either for a single listener or collectively across a group of listeners.

The opening sentence of the following example relates to Toscanini, and Britten’s continued admiration is clear. He had been working for the General Post Office Film Unit since 1935. It is thought that the BBC originally recommended him for the position, and by 1937 Britten was receiving commissions from the BBC to write incidental music for various features and radio dramas:

I go to Toscanini rehearsal in morning—Mozart Jupiter & Schubert C maj—suffice it to say that Toscanini is worthy of such music—the highest praise. The rest of day is spent in hysterical crises at BBC. the production people won’t see that the music sounds bad only because of no rehearsal—finally I threaten to withdraw it—which causes a little sobriety. Very, very disturbing.21

This particular entry from 3 June 1938 highlights another of the complexities of studying a practitioner’s listening experiences. Due to the very nature of Britten’s different roles (as composer, performer and listener), it is not always evident whether a listening experience even occurred, or whether he is merely describing a personal reflection or his account of a particular incident. In the example above it is not entirely clear from the evidence whether Britten actually heard his composition at the BBC or whether it was simply a meeting between himself and the production staff.

Later that same year, Britten received his first Prom commission. This was for a Piano Concerto that he was to premiere with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Henry Wood at the Queen’s Hall on 18 August 1938.22 Unfortunately, there is no report of it in Britten’s diary, which ends abruptly on 15 June of that year.

The period ending in June 1938 is the only one during which Britten kept a daily journal.23 As a source of listening experiences, his diaries provide fascinating insights and an abundance of testimony. They also have the benefit of having been written only for his own eyes; it is highly unlikely that at this age he would have written in his diary with any thought that it might one day be shared (never mind published). Furthermore, the fact that he discontinued the practice of keeping a diary altogether suggests that he had no intention for it to be published. We can therefore read his accounts without applying any sort of filter that might otherwise be needed in the case of the testimony of more established practitioners, who may have had one eye on a later musical public as they wrote. What we read in Britten’s diaries are the unvarnished accounts of his listening experiences.

Conclusion

Britten’s accounts of his own listening experiences provide us with private, unsolicited testimony, illustrating not just what, where and who he was listening to but also the effects that it had on him and how he struggled to express himself. Entering them into LED and extracting the data in an organised way facilitates the analysis of the data both thoroughly and systematically, helping us to understand, for example, which composers and performers he listened to most frequently, and how his tastes and listening habits evolved. With further examination, it might also be possible to see how these changes correlate to his development as a composer.

The reports of the musical events that Britten attended and subsequently recorded in his diaries are, in many ways, typical of a practitioner’s account of listening. In addition to providing an evaluation of their experience, they often include contextual data about the dates and times, the venues, the names of performers and the repertoire being performed. By examining this testimony systematically we learn not only of his tastes and of the performers to whom he listened, but also about the environment in which he listened, the frequency with which he listened to recorded or live music, and a number of other ‘peripheral’ details.

As I have suggested, there are certain limitations with the data. We cannot be certain that Britten reported every listening experience in his diaries. In fact, to assume that these entries were his only experiences would be rather naïve. In 1928, for instance, he only recorded three listening experiences in his diary, but he would undoubtedly have experienced more. This anomaly is principally down to the fact that he only began writing his diary in late September 1928 and the school term ended in mid-November. To begin with, at least, he rarely maintained his diary during the holidays. Furthermore, the date range itself is very limited and we cannot expect these short years to be fully representative of his changing musical allegiances, particularly as he began to engage on a professional career as both a composer and performer. What the data does allow us to observe are patterns, trends and relationships, to either confirm or challenge existing assumptions, which have never been tested in this way. For example, his admiration of Bach and Beethoven is clear, and the dramatic increase in the number of times he listened to Wagner is striking between 1931 and 1934. All of this confirms existing assumptions, but there are other observations that could be made: the different venues that he frequented throughout London (and the fact that so many of his listening experiences were at the Queen’s Hall and the RCM); the sudden change in his listening habits when he moved to London towards the end of 1930; how the increase in his listening experiences via radio broadcasts apparently grew in accordance with his attendance of live performances; and that most were in the company of others, but there was an even split between whether they occurred in public or privately in a domestic setting.

Since the data used in this chapter is on a fairly small scale, much of this analysis could be done manually, but having the data in LED makes the extraction of trends and patterns much easier. Capturing a mass of similar evidence would allow us, for example, to evaluate Britten’s listening habits and practices in the context of others in the same period, social group and/or geographical location. It would also allow us to examine Britten in the context of his contemporaries in other countries and, by extension, listening habits and practices more generally across different cultures and eras.

Select bibliography

Carpenter, H. Benjamin Britten: A Biography. Faber and Faber: London, 1993.

Evans, J. Journeying Boy: The Diaries of the Young Benjamin Britten 1928–1938, Faber and Faber: London, 2009.

Kildea, P. Benjamin Britten: A Life in the Twentieth Century. Penguin Books Ltd: London, 2013.

Mitchell, D. and Reed, P. (eds). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten 1913–1976, Volume 1: 1923–1939. Faber and Faber: London, 1991 .

Mitchell, D. and Reed, P. (eds). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten 1913–1976, Volume 2: 1939–1945. Faber and Faber: London, 1998.

Mitchell, D. and Reed, P. (eds). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten 1913–1976, Volume 3: 1946–1951. Faber and Faber: London, 2002.

Mitchell, D., Reed, P. and Cooke, M. (eds). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten 1913-1976, Volume 4: 1952–1957. Boydell & Brewer: Woodbridge, 2008

Powell, N. Benjamin Britten: A Life For Music. London, Windmill Books: London, 2014.

Reed, P. and Cooke, M. (eds). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten 1913–1976, Volume 5: 1958–1965. Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge, 2010.

Reed, P. and Cooke, M. (eds). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten 1913 –1976, Volume 6: 1966–1976. Boydell & Brewer: Woodbridge, 2012.

You must be logged in to post a comment.