Simon Frith is Tovey Professor of Music at Edinburgh University and a Fellow of the British Academy. He has been a leading figure in the academic study of popular music since the publication of his first book, The Sociology of Rock, in 1978. As a music journalist he wrote for many magazines in Britain and the USA before becoming rock critic of the Sunday Times. He chaired the Mercury Music Prize from 1992 to 2016, and is presently writing a history of live music in Britain. The first volume, covering 1950–1967, was published by Ashgate in 2013.

Abstract

Listening is something we do for ourselves. Sounds reach us through our ears but the musical experience happens inside our heads; it is something to be studied by psychologists and neuroscientists. In this chapter, though, I approach listening as a sociologist, treating it as a social fact. In doing so I address a number of issues.

First, there are many different ways of listening to music: silently, noisily, individually, collectively, by participation and dancing. Second, the differences between ways of listening are often the effect of different listening ideologies. This is well illustrated in social histories of the classical world’s notion of ‘proper’ or ‘serious’ listening, but in popular music studies too we are familiar with the ideological assumptions shaping the different listening conventions of jazz, folk and rock clubs, stadium rock shows and Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals. In both public and private spaces listening disputes are routine. Third, listening is not just what happens in people’s heads. It is a form of social behaviour: to listen is to perform ‘listening’.

Introduction

I have spent much of my life saying to people – parents, friends, colleagues, readers, students, partners, children – ‘listen to this!’ (this being a piece of music). And the question that interests me here is: when we ask people to listen to music what are we asking them to do?

In the context of this chapter, I need to draw a distinction between listening as a musicological skill – to be taught, acquired and assessed, a technical form of musical appreciation, as developed by Donald Francis Tovey, in whose honour my Edinburgh chair is named – and listening as a kind of social skill.1 Implicit in saying to someone ‘listen to this!’ is the command ‘listen to this as I listen to it!’

‘Listen’ here means ‘listen properly’, but this does not necessarily refer to musicological listening. To say to someone, in exasperation (something else I’ve done repeatedly throughout my life), ‘you’re not listening properly’, is not to refer to what is happening in their heads but, rather, to their inappropriate listening behaviour. In social situations ‘listening’ is not an activity that you hear but that you see.

In thinking about listening in this general way, there are three obvious analytic problems. First, listening to music is both a very strange and an absolutely taken-for-granted aspect of human behaviour. Second, there are very many things going on when we are listening: biological, physiological, neurological and psychological, as well as musicological, sociological, and so on. Listening is thus a topic that can be addressed by a variety of disciplines, methodologies and hypotheses. Third, what listening involves cannot be disentangled from the question of who is listening (their knowledge, experience, purpose, personality, and so on), in which places and circumstances. Music listening, in short, involves so many different kinds of activity that any generalisation about it is dubious.

That said, I am a sociologist and generalising is what I do! Let me begin, then, by referring to T. W. Adorno. In his Introduction to Music he wrote:

Asked to say offhand what a sociology of music is, one would probably start by defining it as knowledge of the relation between music and the socially organised individuals who listen to it.2

In practice this meant, as Peter Szendy suggests, that Adorno treated the sociology of music as, in effect, a typology of listening attitudes. This typology depended in turn on a history, ‘the history of the progressive emergence of the notion of a [musical] work.’3

Adorno thus distinguished between the expert listener, the good listener, and the fallen listener. The expert listener is characterised by ‘entirely adequate hearing’:

He would be the fully conscious listener who tends to miss nothing and at the same time, at each moment, accounts to himself for what he has heard … Spontaneously following the course of music, even complicated music, he hears the sequence, hears past, present, and future moments together so that they crystallize into a meaningful context. Simultaneous complexities – in other words, a complicated harmony and polyphony – are separately and distinctly grasped by the expert.

This fully adequate mode of conduct might be called ‘structural hearing.’4

Next we have what Szendy calls a degraded version of the expert listener, the good listener:

Under the prevailing social conditions, making experts of all listeners would of course be an inhumanely utopian enterprise … This is what bestows legitimacy on the type of the ‘good listener’ as opposed to the expert. The good listener too hears beyond musical details, makes connections spontaneously, and judges for good reasons, not just by categories of prestige and by an arbitrary taste; but he is not, or not fully, aware of the technical and structural implications. Having unconsciously mastered its immanent logic, he understands music about the way we understand our own language even though virtually or wholly ignorant of its grammar and syntax.5

And, finally, we have the fallen listener (actually Szendy’s term), for whom music is simply entertainment. These listeners pay no attention to ‘the work’ whatsoever, and it is with reference to fallen listeners that Adorno bemoans the decline of the good listener: ‘The tendency today is to understand everything [the expert listener] or nothing.’6

As many critics of Adorno have pointed out, Adorno’s argument here depends on his particular ‘objective’ concept of the music work, rather than on any kind of study of the subjectivity of listeners themselves. He was uninterested in ‘scientific’ studies of what happened to listeners as they listened (increasing pulse rates, and so on) as leaving out the aesthetic, and would have had even less interest in the Listening Experience Database (LED), dismissing sociological methods based on people ‘verbalising their own musical experiences’ since ‘verbal expression itself is already pre-filtered and its value for a knowledge of primary reactions is thus doubly questionable.’7

I have some sympathy with this view, to which I will return, but, nonetheless, Adorno’s overall argument does point to the conclusion that what listeners do does not much matter, a view he shared with the composer he most admired, Arnold Schoenberg, who famously said he had few if any concerns for the listener or potential listener to his music:

I have as few for him as he has for me. I know only that he exists and that, to the extent that he is not ‘indispensable’ for acoustic reasons (since an empty hall does not resound well), he disturbs me.8

In Adorno’s typology I am certainly a fallen listener both because of my interest in popular music, or entertainment, and because I’m musically illiterate, incapable of listening structurally. But as a sociologist I do find Adorno’s approach useful for raising the three issues that I want to discuss further.

- First, he suggests that there are different ‘ways of listening’ to music, and that these can be organised into typologies, even if not those determined by Adorno’s concept of a musical work.

- Second, he shows that the differences between different ways of listening are the effect of different listening ideologies, different ideas of what music is for.

- Third, he describes listening as a form of social behaviour. Listening, that is to say, is something performed according to particular cultural conventions and as an effect of particular social and technological conditions of listening possibility.

For the rest of this chapter I will explore these issues, though not in such a schematic order. But I’ll end this introductory section with a quote from the wonderful autobiography of Prince Rupert Loewenstein. In 1968 Loewenstein, a merchant banker, was approached by Mick Jagger to see if he would be willing to act as the Rolling Stones’ financial advisor. Loewenstein had no interest in rock and pop music at all. This is his account of listening to the Stones. He had come across the Beatles when, in his words:

we stayed with some cousins in Kitzbühel and as a gift Josephine brought along the latest Beatles LP for our hostess, Sunny Auersperg – later to become, after remarrying, Sunny von Bülow – who was delighted to have it. Sunny played the record while we were there and so I had heard some of the Beatles’ music. Their music was sufficiently harmonic to be acceptable to people like me who only liked classical music. I only really took against rock’n’roll when I heard the Stones.

One of the first times I heard the group play live was very shortly after meeting Mick, at one of the theatres in London’s West End which had started putting on rock concerts … I remember being amused by one aspect of the show that night. At a point when Mick was completely energised and excited, he told the audience, ‘What are you all sitting down for? Get up and let us know what you think.’ How odd, I thought. Surely he must be impressed by us sitting here in silence to admire and take in everything that was going on, rather than getting on our feet and not being able to see properly.9

Ways of listening

Adorno’s typology of listening was determined by his theory of the musical work. Mine is determined by the research I’ve been doing for the last decade on the history of live music in Britain since 1950, involving, among other things, interviews with music promoters. One of our questions was what they thought they were selling as ‘a live music experience’ and how this had shifted over time. One of the things that emerged from their answers is the significance of ideologies of music listening. What promoters have to organise is a musical event that enables audiences to listen to music in an appropriate way. What’s appropriate depends, in turn, on the type of event and the type of music, but what interested us were the circumstances in which this becomes a matter of dispute. Such disputes can take various forms and their resolutions have had significant effects on how events are presented, staged, performed and received.

Our research suggested that there are two different (if overlapping) areas around which most listening arguments have taken place over the last 70 years. The first can be understood as silence versus noise; the second as watching music versus dancing to it. It is from these disputes that I derive my own typology of listening: serious listening, participatory listening and secondary listening. I will discuss each of these in turn.

Serious listening

Serious listening is akin to Adorno’s good listening, but, whereas for him the ‘good’ listener is taking the musical work seriously, for me the ‘serious’ listener is taking the work of listening seriously, which, from a promoter’s perspective, means removing distractions to the listening process. Serious listening is listening in silence; distractions from this, of whatever sort, can thus be described as ‘noise’. This is obviously the ideology of listening in the classical music world and has been much written about, with reference to concert hall behaviour, how serious listening was learned, and so forth.10 I don’t need to go into these arguments here, but will draw from them a couple of points.

First, this is a very self-conscious way of listening; it involves listening to oneself listening. (This is sometimes characterised as ‘musical’ as against everyday listening, but I think this is misleading.) Second, serious listening actually describes listening behaviour – or listening etiquette – rather than what actually may be going on in people’s heads. What matters here is that, whatever is involved in such listening, it must seem to happen in the head. This is the meaning of ‘autonomous reflexive listening’, an understanding that the proper music experience is entirely individual even when it is happening in a public place.11 Such listening has to be displayed for us to know that it is happening, although, from looking at other people listening, we don’t really have any direct knowledge of what is actually going on internally. Eric Clarke describes this well in relation to ‘serious’ listening to the early gramophone in the home:

… the predominant physical attitude in this kind of listening is of people’s eyes fixed to the floor or the elevated middle distance, or closed. Not only does this solve the problem of where to look, but it also reproduces the quasi-religious demeanour that is seen in representations of the audience at concerts and salons in the early nineteenth century, and thus persuades others in the room (who may glance surreptitious around for reassurance) of the significance of each listener’s inner experience.12

But while distractions – noise – can be removed from the listening event, distractions in the head, so to say, can and almost certainly do happen. Listening involves a flux of different degrees of concentration and awareness – consider, for example, Max Richter’s eight-hour work Sleep and people’s accounts of listening to it. From this perspective, ‘serious’ listening is not so much opposed to ‘distracted’ listening as another way of dealing with or thinking about it.

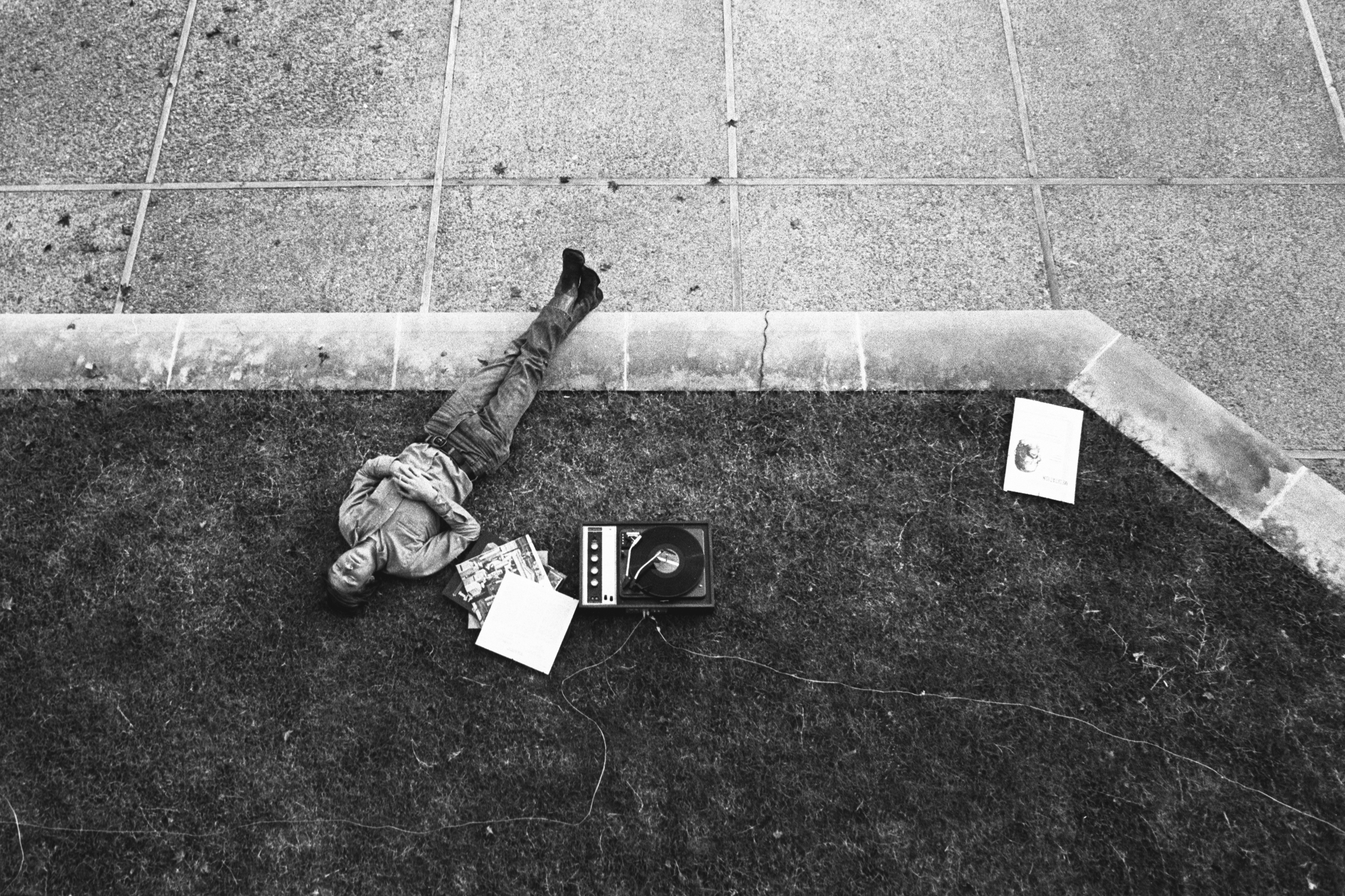

For Adorno, the ‘goodness’ of good listening was determined by the quality of the musical work being listened to, and there is a tendency among classical world people to assume that ‘serious’ listening goes with what they call ‘serious’ music. This is clearly not true. Twentieth-century music technology made possible serious listening to all kinds of music, getting rid of distractions through electrical rather than acoustic means. Radio was thus the key medium in training listeners who were not concertgoers how to listen seriously, and records of popular music could be and were listened to seriously, silently and individually – even in public places. The original jazz clubs in the UK, for example, were places where people gathered to listen to records in silence, before earnestly discussing them.13 More recently, headphones can be understood as a new technological way of making the listening experience private, in the head, even in public. Nowadays, indeed, we don’t even know what someone else is listening to, let alone how they are listening to it. I don’t know of any research on this, but it is surprisingly difficult watching someone on a bus, say, with headphones, to tell from their behaviour what kind of music they are listening to (or, indeed, whether there is any sound coming out of their headphones at all).

Two final points on this.

First, Keith Negus has written an entertaining article on the suspicions of the classical music world (Benjamin Britten, for example) of classical music on television, on the grounds that television was inherently distracting, both as a visual spectacle and as an uncontrollable domestic environment. Britten suggested to the BBC that it would be impossible for listeners to listen seriously to music on television, a point made equally vehemently by a later generation of rock performers and critics.14

Second, colleagues on the Live Music Project, carrying out research on concert audiences at the Queen’s Hall in Edinburgh, found surprisingly little difference between audiences for different kinds of music in their accounts of what makes for a good event or a special musical experience (in terms of being emotionally moved, ‘taken out of oneself’, and so on), despite very different accounts of what counted as being ‘distracted’ from the music (in terms of noise, movement, audience set up, performance space, use of lighting, and so on).15 ‘Serious’ music listening and its counterpart, distracted listening, is not just a feature of classical music ideology, but also an aspect of listening ideology in all music worlds.

Participatory listening

Participatory listening is listening by participating in music-making. This covers a range of activities, from the most direct to the most indirect kinds of participation. Most directly, participatory listening is the listening done by musicians when they are making music – listening to themselves, listening to the other performers, in orchestras, choirs, folk groups, rock bands, and so forth. Note that such listening is an aspect of all music performance, but is indicated differently in different genres and circumstances.

But audiences can also have a sonic participation in musical events, which means that they too listen as musicians, as in the case of call and response, rhythmic clapping and movement, joining in the chorus, or even taking over a verse completely (as at some rock gigs). And there’s also what we might call emotional participation through noise – whooping, screaming, cheering, oohing, shouting, and so on. Again, this is both conventionalised and learned behaviour: such ‘noise’ is not noise in the sense of an interference with the music. This depends what kind of noise is made when: the musical appropriateness or not of the noise made by listeners participating in a musical event depends on the musical genre involved.

Let me cite two examples from other people’s research, published in a special issue of Social Semiotics on live music. Karen Burland and Stephanie Pitts’ concern in their paper on ‘the rules and expectations of jazz gigs’ is what it means to listen to music ‘as a jazz fan’, that is with a particular kind of identity which is brought by an audience to a jazz club but also learned in – and shaped by – their jazz club experience.16 Burland and Pitts suggest that appropriate listening at a jazz club involves: a combination of commitment (fans need to indicate their commitment to jazz as a musical form by their continuous response to what they hear); the right level of comfort (provided by the promoter) with good sound and sightlines, sociable seating and easy access to and from the bar; and connection, a sense of a tangible relationship with both performers and other audience members. What seems to matter most to the jazz audience is that a gig has the right ‘atmosphere’, something that is determined by how the venue is organised and managed, by the behaviour of other audience members, and by the ‘quality’ of performance in terms of its direct engagement with the audience as well as its skill.17

Burland and Pitts’ research also suggests that jazz audiences, at least, must expect a degree of improvisation in how they listen, must decide when to be silent, when to be noisy, when to be still, when to be exuberant – ‘serious’ listening occurs in a context of a deliberate display of emotion. There is thus more audience dissatisfaction at jazz than classical gigs, more irritation with people in the next seats, more grumbling about organisers’ carelessness, more criticism of musicians for misjudging the occasion (whether being too introverted or too extroverted). Participation at a jazz gig is, like improvised music itself, a more unreliable pursuit of musical expectations than attendance at a classical show.

By contrast, Lucy Bennett’s paper on audiences and social media examines the construction of listening behaviour from a quite different angle. Bennett is concerned with a new kind of ‘live’ audience that has emerged in the last decade for pop and rock events, an audience which is present at the events not bodily but via mobile phone access to the internet and on social networking sites.18 For such listeners physical absence from the show itself is compensated by a more intense engagement with what is going on, expressed through a running commentary on the music as it is played. This is an exceptionally noisy audience, but it can’t be heard at all in the auditorium itself. Online, though, such audience exchanges are conventionalised: this kind of fandom involves a strong sense of what is appropriate to say and what kind of fan knowledge gives one the right to say it. The meaning of a musical event has always been shaped by anticipation and recollection; social media both socialise and formalise this temporal arc, condensing the process and making even the most individual emotional flow a matter for public policing. Because this virtual audience can’t be seen listening, their musical response has to be continuously articulated in words. For an absent audience, silence is not an option.

The final kind of participatory listening I want to consider is dancing. Dancing is probably the most important way of listening to popular music; it is certainly the way of listening that is least understood or studied. Anthropologists have always understood that music and dance in many societies cannot be understood as separate activities – see John Blacking’s work, for example19 – but popular music studies have tended to ignore dance altogether or to associate it with particular genres or to treat it as just an interesting but not very significant adjunct to their business of making sense of the music itself. In fact, though, the history of popular music in Britain cannot be disentangled from the history of dance – who dances, where, when and how – this is certainly true of pop music since the 1950s and, indeed, for the whole of the twentieth century.20 I don’t have space to go into this in detail here, but will focus on the consequent listening issue that I have already mentioned, the dispute between people dancing to music and people watching it.

The most familiar of such disputes occurred in the 1950s and 1960s when rock’n’roll acts were put on in all-seater cinemas or town halls; these were the routine battles between ushers and youthful members of the audience, the former trying to stop the latter from standing up and/or dancing in the aisles (although I suspect there were other sections of the audience who would also have liked people to sit down).

But there were other kinds of dispute too. 1950s jazz promoters began to distinguish between two kinds of audience for jazz: those who wanted to watch the band and those who wanted to dance to the music. Having both audiences in the same place – dance halls, for example – caused problems. The watching audience cluttered up the space for dancers and promoters had to decide what sort of venue would best suit a particular act, while some performers (Humphrey Lyttelton, for example) might put on shows for the different audiences in different venues on the same or successive nights.

Note that, while the tensions here (between ‘trad’ and ‘modern’ jazz, for example) might have involved the emergence of serious listening to serious music (the issue therefore still being silence versus noise), initially this was not the primary issue which, rather, concerned the spectacle of performance, sightlines and audience engagement with the musicians on stage rather than with their other audience members on the dance floor. ‘Noise’ was still shorthand for inappropriate listening, but what was being described involved, equally, inappropriate movement.

This was an issue for the new kind of pop idol/record star too. As Melody Maker reported, acts were not always happy about being moved from theatres to dance halls. Bobby Darin, for example, complained that ‘British audiences were the noisiest I have played to anywhere in the world’, making it difficult for him to perform; Heinz gave up playing ballroom dates altogether because he felt their audiences ‘just want a sound’ rather than the ‘visual’ performance he was trying to put across; The Hollies complained that ballroom audiences were too noisy and thus incompatible with the kind of musical experience the band wanted to create. Group members Graham Nash and Eric Haydock preferred the cabaret scene:

I know that the fans like to see us in ballrooms where they feel they can get closer to us, but I would like the future of the Hollies to be in the field of cabaret. We recently played a week in cabaret at Mr. Smith’s Club in Manchester, and we feel we did very well. It gave us a chance to play things like ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’, ‘Stewball’, ‘Taste of Honey’ – numbers we could never do in ballrooms.

‘When we work cabaret it’s different altogether,’ said Eric. ‘Proper dressing rooms, and lighting – and attentive audiences who have come along to listen, and to applaud what they like.’21 The implication here being that in ballrooms fans are not there to listen or, rather, not there to listen in the right way.

For dancers the long-term solution was technological, discos and dance clubs, in which the only performer, the DJ, is usually not there to be seen. Indeed, as Peter Szendy suggests, the DJ’s art may imply ‘less a knowledge of how to play than a knowledge of how to listen’ (just as orchestral conductors are, in effect displaying their listening expertise).22 One could certainly describe the club dance floor as a public performance of a particular kind of music listening.

In the broad shift of dance venues in the 1950s and 1960s, from dance hall to dance club, there were disputes that involved not just generational conflicts, as the needs of young dancers began to inform commercial decisions, nor simply new kinds of etiquette for new kinds of dance – jiving, for instance. The big change was, rather, the rise of dancing as individual expression and the decline of the authority of the dance band leader and dance teacher, the end of dancing as a matter of following formal, collective rules of how to move. The established dance halls felt this as a threat of disorder though, in practice, as autobiographical accounts of Northern Soul make clear, such individualised dancing took place in spaces with new social conventions of listening and dancing that had to be learned.23

Secondary listening

I’ve been discussing listening as watching and I need to clarify this concept, given that all live music involves performance, involves something to see as well as something to hear. To put it too simply, one could say that, for serious listeners, sound is more important than sight (it doesn’t seem odd for a member of the audience at a classical concert to listen to the whole thing with their eyes shut). For participatory listeners, sight and sound are equally important, although musicians may not be the sight or performance that matters as against, say, other members of the audience or, indeed, the use of lights in a club.

For secondary listeners, by contrast, what’s heard is subordinate to what is seen. This is most obvious in the way we listen to music while watching a film in the cinema or programme on TV, but there is a long tradition in popular culture of music listening being related to spectacle, whether as an aspect of popular entertainment such as circuses and fairgrounds or in popular theatrical forms such as melodramas and vaudeville (and, of course, both opera and musicals remain problematic for ideologues of serious listening, whether from classical or popular music studies). These are the kinds of musical performance in which direct communication from star to audience is most apparent. For serious listeners of all sorts, the trappings that make a musical performance spectacular – the ‘show’, the ‘got-up-glitter’, the ‘vulgarity’ to use Hubert Parry’s words – are what makes certain kinds of music trivial or corrupted, what leads them to be dismissed as ‘entertainment’.24

Parry was contrasting music hall to ‘true folk-songs’ (though his argument is not dissimilar to the punk-inflected critique of the stage excesses of post-prog rock bands in the 1970s), but the point here is that spectacle doesn’t take anything away from ‘real’ musical experience; rather, it offers a different sort of musical experience, in which the pleasure lies in the sensual overload (as, for example, in the contemporary stadium show, with its complex lighting board, sound design and use of video). It is impossible to describe what it means to ‘listen’ to a performance by Pink Floyd or Beyoncé, by Muse or Madonna, without simultaneously describing what is seen.

Conclusion

I want to end on a different note, by returning to the issue of serious or musical listening and the suggestion that the musical experience is something that happens inside the head. For all the analytic problems of this argument, it remains the common sense of much academic and non-academic discussion of what we are doing when we are listening to music.

Now, in one sense, a sociologist is not well equipped to explain what happens in people’s heads, although there is such a thing as phenomenological sociology, but I can say something about the social and ideological conditions that enable music listening to be understood like this, in terms of self-analysis, and the cultural conditions in which the musical experience becomes so closely related to our sense of identity. To put it simply, it was the development of societies in which the sense of the individual self was important that has created our ability – and the necessity – to listen to music this way, as a means of self-analysis.

Still, in reading various accounts of music ‘in the head’ I have been struck by the vagueness of the descriptions. The philosopher Peter Szendy writes of the importance of a certain inattention, a wavering of concentration, to the way in which we make sense of music. The music psychologist Eric Clarke describes the listener’s ‘contemplative perceptual attitude’ in terms of the ‘inner reality of virtual structures, journeys, narratives and action.’ The popular music scholar Franco Fabbri describes music listening as akin to the Italian concept of dormiviglia, a mental vigil in between consciousness and sleep. In each of these accounts there is, then, a suggestion that listening to music is something like dreaming, something apparent in LED too.25

One aspect of this is something that Adam Smith described, the analogy we draw between the movements of sounds as we listen to music and the movement of the mind as we experience or express different feelings.26 Hence the way that the musical experience is often made sense of in terms of emotions, in language of feeling into which the musical experience is translated, as it were.

The pleasure of music for Smith was that it gave us a way of reflecting on our own emotions and the brain work that they required, without the usual distractions of cause and consequence, and Smith was, after all, a key figure in putting individual self-consciousness and desires at the heart of moral philosophy and political economy. Following his lead, one could certainly argue plausibly (if against the usual critical approach) that all those people sitting in silent intensity through, say, a Mahler symphony are actually thinking about themselves rather than about Mahler.

But this doesn’t feel quite right. If serious listening to music is like dreaming, then it is with a clear sense that something – the music – is in control of that dream, even if we are peopling it with our own vague feelings and imagery. I take from Szendy’s work the implicit suggestion that, while listening is not reading, a comparison between the two can shed light on both. We can point, for example, to the historically parallel emergence of ‘serious ‘or ‘literary’ reading as also being something silent, concentrated, in the head. We find too in reader-response theory the suggestion that reading, like listening, involves the use of the reader’s own imagination, what is being imagined triggered by the words out there but filled out by our own imaginative work in the act of reading.

Novels, poems and pieces of music thus all involve a myriad of individual forms of ‘completion’, which explains how we can feel that a performed version articulating someone else’s imagination of the work – a TV adaptation, a particular arrangement or performance, has got it wrong (which is why the listening accounts in LED tell us things about the listener rather than about the music to which they were listening).27 But there is an indication here too of the differences between listening and reading. What we hear is music as performed by someone else; as readers we perform the work for ourselves (and this is, of course, also the difference between novels and plays).

There is much more to be said about this, and about the possibilities and the difficulties of applying reader-response theory to musical experience. But my final point concerns another difference between music and literature or, rather, between music-without-words, instrumental music of all sorts, and literature and other word-bound art forms. Instrumental music is not obviously or even essentially about anything; listening does not necessarily involve a relentless pursuit of meaning.

Adorno’s ‘expert’ listener apparently rebuffed this suggestion by saying that the meaning of the music, what needs to be understood, is its structure. The ‘work’ has to be heard in order to understand what we are hearing. Such analytic listening is possibly a way of listening necessary for composers, conductors and certain kinds of musicologists, but I don’t think it describes what serious listening means as an aesthetic experience, as something pleasurable.

Serious listening, unlike other forms of musical listening, for me involves putting myself in a position to be able to listen to music without thought, not trying to control what’s happening in my head but, rather, letting the music do that. Perhaps, to return to the typology of listening, ‘serious’ listening should be retitled as ‘thoughtless’ listening, listening without the distraction of thought.

Select bibliography

Clarke, Eric. ‘The impact of recording on listening’, Twentieth-Century Music, 4(1), 2007.

Szendy, Peter. Listen. A History of Our Ears. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

Social Semiotics (Special Issue on Live Music), 22(5), 2012.