Chloë Alaghband-Zadeh is a Research Fellow at Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge. Her research is on North Indian classical music, which she studies through a combination of ethnography and music analysis. She received her PhD from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London (2013), for a dissertation on the semi-classical genre ṭhumrī. She is currently working on a project on expert listening and connoisseurship in North Indian classical music.

Abstract

With this chapter, I explore the social meanings of embodied ways of listening to North Indian classical music. I focus especially on still, silent listening, a mode of listening that has been neglected in scholarship in this context. This scholarly neglect reflects the fact that most North Indian classical musicians and listeners tend either not to discuss this form of listening or else to cast it in a negative light, preferring instead to celebrate more active, noisy ways of listening to music. However, by not considering the full range of listening practices at North Indian classical performances, scholars have not theorised how competing value systems shape different ways of listening within a single performance environment. Here, I consider how certain North Indian classical musicians and listeners invest still, silent listening with positive significance. I argue that embodied modes of attending to music are implicated in social negotiations over prestige and status. Moreover, embodied listening demeanours have the power to reproduce musical ideologies.

Introduction

What shapes the embodied ways listeners engage with music? What are the social meanings of embodied listening practices? And what can scholars learn by asking listeners about their listening behaviours and experiences?

A diverse field of embodied listening behaviours can be observed at live performances of North Indian classical music. At a typical performance, some listeners sit still, perhaps with their eyes closed, silently attending to the music. Others are more conspicuous. They interact with the musicians and with each other throughout the performance and frequently comment out loud or gesture in response to the music.

I am interested in the sociality of these embodied listening practices. With this chapter, I explore the significance listeners attach to embodied ways of engaging with music. I focus on still, silent listening, an area neglected in scholarship on North Indian classical music; I consider what this particular listening practice means in the context of contemporary performances of North Indian classical music. This research is based on ethnography and interviews with musicians and listeners. By asking listeners about their listening experiences, I highlight powerful intersections between embodied listening practices and (verbal) discourse on music. I show how individual listeners each mobilise the discursive resources available to them in order to make sense of their listening behaviours, preferences and experiences. Moreover, I argue that embodied ways of listening to North Indian classical music sustain particular musical ideologies.

This work builds on diverse existing scholarship on the embodiment of ways of listening to music.1 This has included work on still, silent listening in various global contexts. In Listening in Paris, a study of the ‘historical construction of listening’ in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Paris, James Johnson links the emergence of still, silent listening practices with broad shifts in musical ideology (towards romanticism).2 The ethnomusicologist Lorraine Plourde, meanwhile, has discussed the still, silent practices of listeners to the Japanese new music genre onkyo. She links their particular ways of listening to the aesthetic of the music and shows how listeners’ experiences and behaviour were shaped by pamphlets and other written materials, as part of a niche culture of musical connoisseurship.3

This chapter is especially inspired by the work of Jonathan Gross. He has conducted a rich ethnographic study of audiences for the BBC Proms (a concert series of mainly western classical music held in the prestigious Albert Hall every summer in London).4 He uses interviews with individual listeners in order to examine the social norm of still and silent listening, exploring ‘the ends to which diverse audiences put this very particular way of using music’.5 He argues that listeners practise this behaviour in part ‘in order to cultivate versions of themselves (that is, as ‘technologies of the self)’.6

Like Johnson and Plourde, my aim here is to highlight relationships between conventional (embodied) listening behaviours and ways of thinking about music. Like Gross, I am interested in the individual ways in which listeners make sense of their own embodied listening practices; I will show how shared discourses and ideologies intersect with the personal ways listeners engage with North Indian classical music. In doing so, I draw on Gross’ idea that listening can function as a ‘mode of using music’, a way for individuals to fulfil social and emotional needs.7

This chapter also contributes to a growing body of research on the embodied listening practices of North Indian classical music. So far, however, this work has focused on the behaviour of the most active, noisy listeners at North Indian classical concerts.8 Often great musical experts, these listeners demonstrate their musical engagement with their bodies and voices: they gesture or comment out loud during performances, as a way of signalling their appreciation for what the performers are doing. Through their embodied and audible reactions to music, they show what they make of what they are hearing, both to the performers on stage and also to each other.

It is not surprising that these extrovert listeners have been the focus of most scholarship on North Indian classical listening so far: they are conspicuous at concerts and their ways of listening are valued by musicians and listeners alike. However, not all listeners engage with North Indian classical music in this way. Some audience members move and talk more than others. Many do not move or talk at all. Despite this, scholars have largely ignored the still, silent mode of listening in this tradition. I will suggest, however, that there is much to gain by examining this way of listening to North Indian classical music: as I will demonstrate, this can shed light on powerful intersections between embodied ways of listening, on the one hand, and ideologies of music, on the other.

With this chapter, I consider how listeners make sense of (and, following Gross, make use of) still, silent listening practices at performances of North Indian classical music.9 This work is based on ethnography and interviews with musicians and music-lovers in Delhi, Mumbai and Pune, conducted during research trips in 2014 and in 2015. As part of this fieldwork, I conducted formal interviews with 20 music-lovers. I also arranged a series of listening and discussion sessions, attended concerts and other musical events, and had many informal conversations with musicians and listeners. During my interviews, I asked listeners about their listening experiences at live performances. This is the main source of data I employ here: in what follows, I quote from a number of these interviews, in all cases anonymising the names of my participants.

Based on this research, I highlight the social meanings of embodied ways of listening to North Indian classical music. I discuss some of the individual and highly personal ways listeners make use of the listening behaviours available to them. In doing so, I consider the implications of the fact that there are social boundaries around the most valued and high-status ways of listening: these listening practices are more accessible to some listeners than others. By focusing on still, silent listening in this context, I show how some individuals rationalise and legitimise a typically devalued mode of listening to North Indian classical music. Finally, I explore ways in which discourses on embodied ways of listening intersect with other discourses and musical ideologies. In particular, I draw attention to powerful meeting points between ideas about still, silent listening and a discourse of spirituality in North Indian classical music. I argue that the coexistence of different modes of listening to North Indian classical music is a result of (and reproduces) a complex discursive field, shaped by competing musical ideologies, themselves the traces of particular, intertwined histories in the tradition. Thus I suggest that musical ideologies in this context are performed and sustained, in part, through listeners’ embodied engagement with North Indian classical music.

Noisy, active listening versus still, silent listening in India

At the performances of North Indian classical music I attended in Delhi, Mumbai and Pune, audience members displayed a range of embodied listening practices, including noisy, active listening and still, silent listening. These different practices, however, do not have equal value.

Noisy, active listening has a privileged position at performances of North Indian classical music. It is valued by musicians and listeners alike. As Martin Clayton and Laura Leante have shown, listeners’ gestural and audible contributions are integral to North Indian classical performances. For example, Clayton writes that:

it appears to be more productive to see the performance as an event constituted by all its participants, rather than to see the audience as the ‘context’ for the musicians’ performance.10

This co-production is a source of value for performers and listeners. Musicians value the instant feedback they get from the most active listeners, which allows them to gauge how their performances are going, helping them to decide what and for how long to perform. Some musicians also told me that a responsive audience can help them to perform at their best. Expert music-lovers expressed great pride in the fact that their contributions are crucial to a successful performance.

Conspicuous, noisy listening also serves important social functions. Responding to music with gestures and comments can be a way for listeners to perform the high-status, prestigious, classed identity of the rasika, or music connoisseur, as I discuss elsewhere.11 Being a rasika is often associated with having musical expertise; and so many musicians and listeners take an active audience as a sign that that audience is knowledgeable. For example, the music organiser Raj told me that a knowledgeable audience would usually be ‘a little more responsive than the non-knowing audience’. He said that when there is ‘an audience which knows what is happening’ and ‘approves of what is happening’, that that ‘[generates] a little more positivity into it’. And, as well as implying musical expertise, responding audibly and visibly to music also has positive ethical connotations, evoking generosity, sincerity and patience. Many associate this behaviour with a past Golden Age of North Indian classical music.12

On the other hand, many listeners see still, silent listening as a problem: they interpret it as a sign that listeners are not engaged in the performance, as evidence of an undiscerning, ignorant audience, or as a symptom of North Indian classical music’s much lamented move from small, intimate performance environments, to large, impersonal concert halls.

For example, Radha, a lifelong music-lover, told me that the best kind of audience is an ‘appreciative audience’. She compared this with audiences who do not appear to be listening to the performance, who, she said, made her feel ‘sad’. Likewise, Sunny, another very keen music-lover, compared the ‘very good’ audiences he remembered in Calcutta in the 1970s, who were very active, with an audience he had recently seen on the television:

I remember this guy, this nice guy […] – in Calcutta I used to go to these concerts – it was a guy sitting and he would just go absolutely like he was having an epileptic fit almost: his reaction to the music [was] like that. And talking about listening like that, it’s really funny: I was watching some classical music concert on TV the other day, recently, and when they’re panning the audience, […] the singer is doing his best, he is singing, it wasn’t bad, but the audience, my goodness! People looked like, Jesus, is this a depression? Everybody looked like the last thing they enjoyed was music.

For Sunny, then, not responding to music is a sign of a lack of enjoyment. He makes clear that the music here was good and that the singer was not at fault. Rather, these immobile listeners themselves must be to blame. The implication is that they are deficient as listeners, unable to discern good music from bad.

There are various practical reasons why listeners might not participate in active, noisy listening. Newcomers and audiences outside India may simply not be familiar with these conventional ways of responding to music. Audience members may feel uninspired, or not in the mood to respond conspicuously during a performance; or they might find it difficult to engage with an uncommunicative musician. Many listeners believe that it is more difficult to interact with musicians in a large concert hall than in a small, intimate environment. And certain parts of the music seem to invite responses more than others. (As John Napier, Martin Clayton and Laura Leante have documented, interaction between performers and audiences is often fairly limited at the start of a performance, but intensifies as the performance continues.)13

Active, audible listening practices are also distributed (unevenly) according to social hierarchies. Brian Silver, for example, has considered how the different social status of audience members in influences their behaviour at performances. Social status, in this context, is determined by a variety of factors, including age, gender, whether one is a patron or ‘honored guest’ and, importantly, musical expertise. Silver notes that it is the audience members with the highest social status who tend to sit closest to the musician during the performance and it is with them that musicians interact the most.14 Similarly, Leante has described how both status and the ‘expected degree of freedom of interaction with the performers’ are ‘directly proportional to the proximity to the stage’.15 As Clayton and Leante have shown, social hierarchies at performances of North Indian classical music are both spatialised (that is, distributed unevenly in the performance space) and also embodied (made manifest in the different embodied demeanours of that individuals present).16

This spatialised, embodied social hierarchy is sustained in part through social policing. For example, Brian Silver describes how soloists might ‘deliver a lecture’ during a performance to ‘presumptuous’ junior musicians who are ‘too vocal in their praise’ of a performance ‘in an attempt to attraction’.17 Similarly, the music-lover and amateur performer Ravi told me that, although he would not generally ‘be bothered about judging other listeners’, he does disapprove of those who ‘[make] a nuisance of themselves’ by being ‘too loud’. Daniel Neuman has also discussed the risks for non-experts of participating in noisy, active listening in this context: ‘inappropriately timed responses’ can reveal a person’s musical ‘naivete’.18 In each of these cases, an individual’s audible responses to music expose them to criticism (and moral judgement) from musicians or other listeners. Elsewhere, I have discussed other examples of the ways extrovert listening behaviours are policed at performances of North Indian classical music: I show how the social boundaries around these listening practices reproduce social hierarchies within the music world (especially around levels of expertise) and also broader class distinctions.19 Although participating in noisy, active listening affords unique pleasures and offers the promise of social rewards (especially for the most high-status listeners), it also carries risks.

The different kinds of listening behaviours evident at performances of North Indian classical music are thoroughly implicated in social hierarchies and questions of value. In this context, musicians and music-lovers typically view still, silent listening in a negative light, often interpreting it as a sign of ignorant or unengaged listeners. However, there are various reasons (including social policing) why some listeners might nevertheless adopt still, silent listening practices at performances of North Indian classical music. In the next section, I will consider how individual listeners inhabit this generally devalued mode of embodied listening.

How listeners make sense of still, silent listening

How do still, silent listeners make sense of their listening experiences? In contrast with most music-lovers’ frequent celebrations of extrovert listening practices, a minority of the music-lovers I interviewed invested still, silent listening with positive significance. They included some very expert listeners and patrons, with a high status in the music world. These listeners understood still, silent listening not as inexpert or inattentive, but rather as a legitimate and valuable way of engaging with music. In this section, I shall explore how these listeners craft this minority position, drawing on the discursive resources available to them in order to negotiate with the dominant position on listening still and silently to North Indian classical music. I shall show how, for certain listeners, listening in this way is what Gross calls a ‘mode of using music’: a pattern of behaviour which people can take up and employ, according to their own individual needs.

Shivika, a prominent music organiser, made the case for still, silent listening by drawing attention to the negative side of noisy, active listening. She said:

A person like me, I will not say ‘Ah, ah, ah, ah!’ I don’t want to attract attention to myself. I may say a subtle ‘Vāh!’ [Wow!] or ‘Ah!’ […] But there are some people: ‘Are vāh! Are kyā!’ You have seen [it]. So sometimes people also do a lot of theatrics.

She interpreted these ‘theatrics’ as a sign that audience members want to show off, asserting their superiority over others. As she put it:

Some people, meaning connoisseurs, they want to let other people know, ‘Here is what I understand.’ You know that person has come on the sam [the first beat of the metrical cycle] and I understood. And if you have not understood … It is not only very innocent appreciation, genuine appreciation of good but is also, ‘Oh, that happened and I knew it; I understood it; I understand it.’

Here, Shivika highlights a negative aspect of the fact that noisy, active listening can be a performance of expertise: this exposes the more extrovert listeners to the accusation that they are not being ‘genuine’. For Shivika, listening quietly is not a sign of ignorance or inattentiveness, but part of how she is able to take a principled stance about enjoying music in a genuine way and not showing off. In Gross’ terms, listening in a restrained way is a means by which Shivika cultivates a version of herself that is ‘genuine’ or authentic.

Similarly, the music patron and connoisseur Arun told me that in the ideal kinds of performances, with a small number of expert listeners, noisy, active listening can be unnecessary:

So, within a […] space of ten or fifteen listeners, and the artist who is really doing a magnificent job, something great is happening. And you know something great is happening because you have had a history with the same artist and you have had a history with the same music, a history with the same rag, even a history with most fabulous accompaniment coming together, you know, collaboratively. [It’s] an ambiance. You have friends, an artist is coming: it takes a lot of things for something really, really great to happen. When it’s happening, you’re part of it. You’re happy to be part of it and you are silent, my dear.

He described his experience of listening silently at a small house concert as a ‘reverie’ and an ‘inner purge’, and said, ‘If something magnificent is going on, […] it transcends vāh vāhs and all that.’ Here, Arun reverses the usual formulation, in which interaction between musician and audience is associated primarily with intimate performance environments; for him, silence is the ultimate sign of musical enjoyment in such contexts.

At another point in our conversation, he compared this with his experiences of western classical music:

Sometimes when the going is good, […] you’re just caught up in the sheer magic of the music and you’d rather keep [your eyes] closed, like sometimes when you’re listening to great Bach, even on headphones, you keep your eyes closed. Or Chopin.

One might speculate that it is in part his engagement with western classical music which caused him to adopt this embodied demeanour (which is normative in the context of western classical listening) in relation to Indian classical music.

Meanwhile, where he did discuss the advantages of noisy, active listening, he framed this in pragmatic terms, telling me that he might praise a tabla player out loud if they appear to be taking over the performance with too much virtuosity, to ‘cajole’ them into being more ‘sedate’. Like Shivika, Arun too understands still, silent listening as a more genuine engagement with music than the more conspicuous, extrovert embodied mode. For him, listening silently is what happens when one is ‘caught up in the sheer magic of music’; responding audibly to music, on the other hand, is only necessary as a way of manipulating certain musicians into holding back, lest they mar the performance.

Another theme that came up in a number of my interviews was the idea that getting people to close their eyes could be a good way of enticing newcomers to North Indian classical music. As well as the fact that non-experts are subject to social policing when they engage in extrovert listening, getting people to close their eyes is often used as a strategy to encourage beginners to engage with the music.

Chirag, a prominent listener and music organiser, described a listening session he had organised, featuring the renowned santur player Shivkumar Sharma:

See I give an example of Pandit Shivkumar Sharma. He had come for a lecture demonstration in the afternoon. We used to have this thing on Saturday afternoon, soon after college, so that students, before they go home, they could get a taste of this music. […] And he said, ‘Now I am going to play an ālāp. And an ālāp, it’s a gradual development of the ālāp, without any percussion instrument. But I will request the whole audience to close your eyes and listen.’ After those ten or twenty minutes, the ālāp, then he would say, pick up someone, a young lady, ‘What did you feel while listening?’ Somebody would say, ‘I could hear waters gushing from a river, or from the mountains.’ Somebody would say, ‘I am seeing the image of some god.’ Somebody would say, ‘I feel saddened.’ The effect of music on different people at the same time! […] And [this was] how he created an audience.

According to this anecdote, an extremely famous North Indian classical musician asks an audience of non-experts to close their eyes as a way of fostering engagement with the music. Since non-experts are liable to face social policing for engaging in noisy, active listening, this makes sense; but by telling this story, Chirag also invested this mode of listening with positive significance, as something which can improve listeners’ engagement with music. This anecdote served to validate this as a legitimate mode of listening.

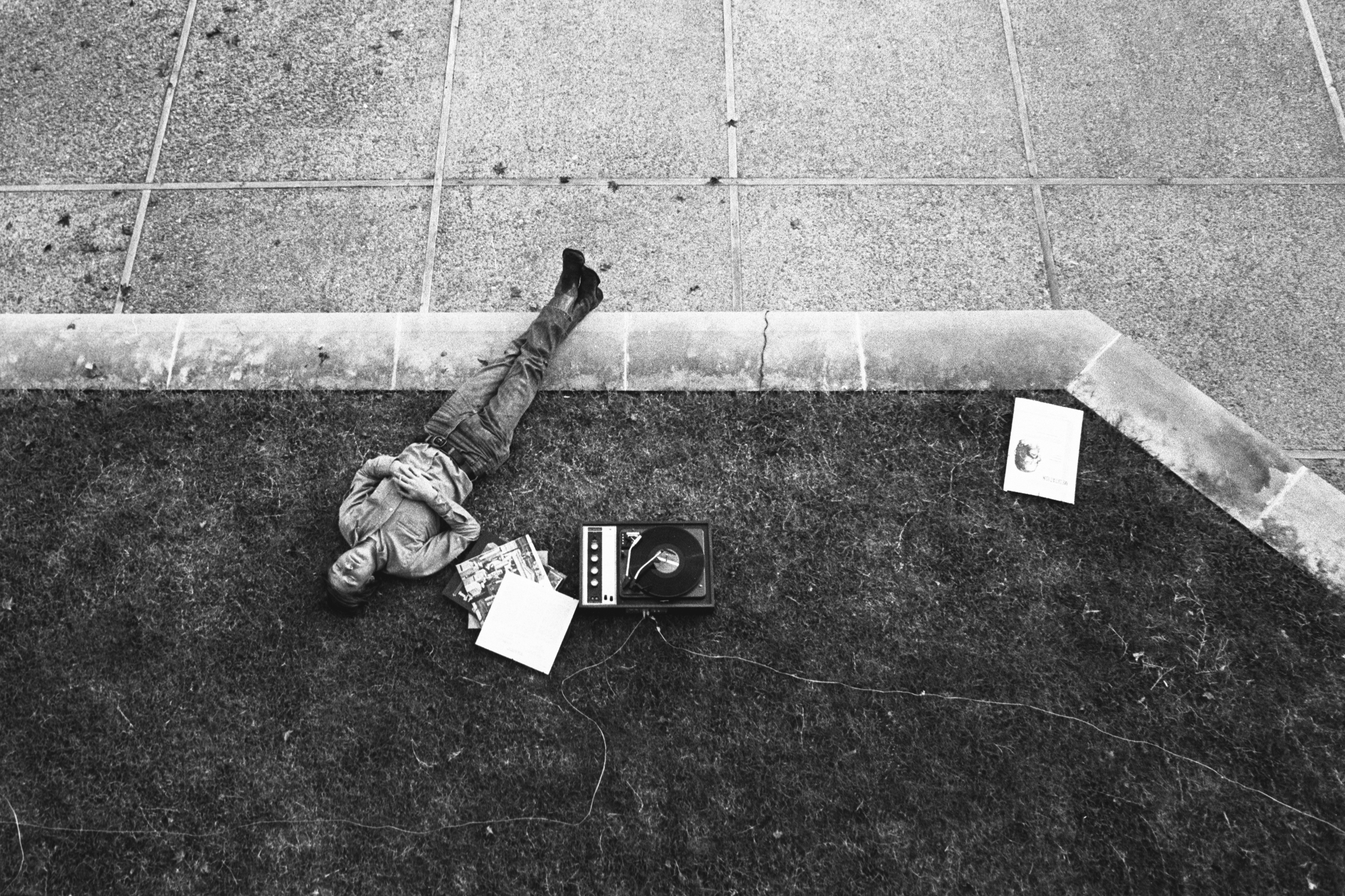

Note here also how the mechanism of closing one’s eyes produced various statements that sit within a broader discourse of spirituality in North Indian classical music, such as the listener who is reported to have said that they saw ‘the image of some god’ on hearing this music. This was typical of a broader trend. Ideas about spirituality or meditation came up frequently when listeners made the case for still, silent listening. A discourse of spirituality informed Arun’s description of listening to music (above), in which he described it as an ‘inner purge’. Similarly, it also coloured this description of still and silent listening by Shekhar, a record collector. He told me:

Well when I am listening in a concert, by default I am not allowed to even look at the other person nor speak. So usually I will sit in yogic posture, eyes closed. Because I will enjoy myself. And even if somebody is making a comment, I will feel offended.

Another prominent organiser, Neeraj, also used the language of spirituality when he described his embodied engagement with a particular instrument:

If I listen to a flute, of a certain particular person, I go into a trance. But the same raga if it is played on sitar, my responses are totally different. […] Vocal music, my responses are totally different. I’d hardly do any vāh vāh and ah ah for the flute. […] After time, people think that I am asleep, but I am not. I go into a trance. I enjoy each and every note. […] I may just nod, ‘Aha!’ like this, to myself, because my eyes are closed.

In each of these cases, listeners drew on a shared set of ideas about music as an inner, spiritual experience in order to craft their own discursive stances on still, silent listening practices.

Thus for certain listeners, listening still and silently goes beyond simply not participating in the noisy, active listening that characterises the tradition. Rather, they find their own ways of understanding and representing their listening in a positive light. For some, listening in this way is tied to ideas about being genuine or authentic, while for others it signifies spirituality or a way for newcomers to engage with North Indian classical music. In the next section, I will consider what broader ideological work is being done through these individual discursive negotiations on ways of listening.

Embodying discourse and ideology

What is the relationship between embodied ways of listening to North Indian classical music, the individual ways in which listeners make sense of their listening experiences, and the broader discursive landscape of the tradition? My discussions with listeners about still, silent listening revealed how shared sets of ideas have emerged around a generally devalued mode of listening to North Indian classical music. Listeners individually mobilise the discursive resources available to them in order to invest their embodied ways of listening with positive significance; however, although each listener I spoke with crafted their own, unique position, certain themes came up repeatedly.

Most often, still, silent listeners understood their own listening in terms of spirituality and meditation. Such ideas are an important part of the discursive landscape of North Indian classical music.20 (They have also been central to western appropriations of North Indian classical music.)21

A similar discourse on spirituality is a common lens through which North Indian classical musicians and listeners understand musicians’ embodied demeanour in performance. John Napier has described how performers commonly start their performances with a ‘closed-eyed, self-contained demeanour’, before gradually becoming more animated and interacting more with their audiences. He writes that this ‘self-contained’ embodied stance gives the impression of ‘drawing on the subconscious’, linking this with ‘the long-standing association of Indian performance with an almost meditative act’.22

As Napier observed, some musicians I interviewed also drew a link between closing one’s eyes and meditation. For example, the singer Urvashi described how ‘when I reach that state of meditative level of consciousness in my music, then once in a while I might just shut my eyes and go in deep within’.

Meghna, an amateur singer, too, told me that:

You get into a different zone, so even when you are performing you really don’t pay attention to the audience beyond a point, or at least I don’t. You get into a zone which is much more about you, the music and the higher self. It’s like a very, a very sort of self-contained space. […] When you are listening as well you enter that level of space. It’s very similar in a way. It’s not a self-conscious space at all. […] It’s very meditative and it’s very – it really takes you into a different realm.

This was in tune with her other comments about North Indian classical music. Throughout our discussion, she emphasised the spiritual dimensions of North Indian classical music, saying that for her music is a source ‘of beauty, of something that comes closest to a spiritual experience’. Thus there are parallels between the ways certain listeners understand still, silent listening as a spiritual or meditative act and a wider discourse on embodied spirituality, typically applied to musicians.

Moreover, this discourse on the embodied spirituality of musicians is itself one side of a discursive binary surrounding North Indian classical music, in which ways of understanding of music as spiritual compete with courtly associations. Daniel Neuman has discussed the semiotics of different performance styles adopted by musicians. He compares what he calls a courtly (or darbār) model of performance with a devotional (or bhakti) model, and notes some of the implications this has in terms of performers’ stage behaviour and dress. He further suggests that these ‘represent the bipolar traditions of music as a way for and a way of life’ and ‘continue a fundamental ambivalence in the meaning of musicianship’ in North Indian classical music.23 Likewise, in Brian Silver’s book chapter ‘The Adab of musicians’, he describes what he calls two ‘behavioural models’ available to musicians: the ‘simple man’ and the ‘courtly man’. In his description, while the ‘simple man’ pursues music as an expression of spirituality, the ‘courtly man’ cultivates an aristocratic musical demeanour.24 These different embodied demeanours are the traces of different (but frequently overlapping) imagined histories for North Indian classical music: while some musicians and listeners link contemporary North Indian classical music primarily to its Mughal, courtly past, others prefer to emphasise pre-Mughal musical practice, hearing music primarily in terms of Hindu spirituality.25

I would suggest that the models of listening behaviour I have discussed here are indicative of that same discursive binary, between courtly and spiritual understandings of music. While extrovert listening practices tend to be associated with past courtly patronage, courtly etiquette and elite, expert connoisseurship, still, silent listening is more often aligned with ideas about spirituality and the universality of musical expression. Ways of listening are thus implicated in wider conceptual frameworks for understanding music. They are shaped by competing ways of understanding music. Moreover, these two kinds of embodied listening are an important way in which these discourses are internalised, performed and reproduced.

As well as a discourse of spirituality, attitudes to the embodied aspects of listening also intersect with other discourses, too. Recall how, in Chirag’s anecdote (above), a spiritual interpretation of music was aligned with ideas about making the tradition accessible to newcomers. This in turn resonates with a broader ideology of the universalism of North Indian classical music. This ideology circulates through discussions about the extent to which expertise and musical knowledge are necessary for someone to be a ‘good’ listener of North Indian classical music. While some musicians and listeners believe that experts make the best audiences for North Indian classical music, others think that the tradition is, and ought to be, accessible to everyone. Thus celebrating still, silent listening can support a particular ideological position on musical universality.

In linking ideas about spirituality with ideas about musical universality, Chirag makes a common discursive move. Note how Urvashi also uses the idea of spirituality in order to support her view that musical knowledge is not necessary for someone to have a legitimate musical experience. She described a concert she had given at which:

Everybody in the audience had tears in their eyes. […] I sang […] a beautiful composition on Shiva [a Hindu deity]. And it was Shivaratri [a Hindu festival associated with Shiva]. So it’s like everybody said, ‘We literally felt we could see Shiva sitting there in meditation.’ They all had that kind of spiritual experience – for a spiritual experience, you don’t need to know which is which svar [note].

This stance is in line with Urvashi’s personal career trajectory. She is a performer who has had a successful international career, performing frequently outside of India. For Urvashi, highlighting the spirituality of still, silent listening is a means of legitimising the way in which many of her audiences engage with North Indian classical music. She also, by extension, validates her own position as someone who performs to such audiences and the broader idea that North Indian classical music should be for everybody, not just the experts.

Thus, in each of the cases I have discussed in this chapter, listeners form their positions on listening by drawing in their own way on the shared discursive resources available to them. These, in turn, intersect with and reproduce broader musical ideologies. In this context, embodiment, discourse and musical experience are thoroughly interrelated.

Conclusion

With this chapter, I have discussed some of the social meanings of embodied ways of listening to music. I identified two contrasting modes of listening to North Indian classical music and explored some of the ways contemporary listeners make sense of their own embodied listening behaviours. I showed how certain listeners have negotiated with the normative model of listening in this tradition, imbuing still, silent listening with positive significance. And I considered ways in which attitudes to listening intersect with and reproduce broader discourses and musical ideologies.

This work highlights how discourse and musical ideologies can be variously embodied in, and reproduced through, listeners’ ways of attending to music in performance. Ways of listening to live performances are shaped by broader sets of ideas about music and musicians. As a result, the choices individuals make about how to attend to music are deeply meaningful. By listening to music in particular ways, listeners take a position within competing discourses on music, with implications in terms of prestige and social status.

Ways of listening are not ideologically neutral. Individuals understand and employ listening practices in highly personal ways, specific to their own unique circumstances and agendas; but embodied listening practices are also implicated in broader discursive negotiations. Embodied ways of listening are thus deeply personal, while they also have the power to sustain collective musical ideologies.

Select bibliography

Alaghband-Zadeh, Chloe. ‘Listening to North Indian classical music: how embodied ways of listening perform imagined histories and social class’, Ethnomusicology 61, no. 2, 2017 (forthcoming).

Clayton, Martin. ‘Time, gesture and attention in a Khyāl performance’, Asian Music 38, no. 2, 2007, pp. 71–96, doi:10.1353/amu.2007.0032, accessed 10 March 2017.

Clayton, Martin and Leante, Laura. ‘Role, status and hierarchy in the performance of North Indian classical music’, Ethnomusicology Forum 24, no. 3, 2015, pp. 414–442, doi:10.1080/17411912.2015.1091272, accessed 10 March 2017.

Gross, Jonathan. ‘Concert going in everyday life: an ethnography of still and silent listening at the BBC Proms’, PhD dissertation. Birkbeck College, University of London, 2012.

Johnson, James H. Listening in Paris: A Cultural History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Neuman, Daniel Moses. The Life of Music in North India: The Organization of an Artistic Tradition. New Delhi: Manohar, 1990.

Plourde, Lorraine. ‘Disciplined listening in Tokyo: Onkyō and non-intentional sounds’, Ethnomusicology 52, no. 2, 2008, pp. 270–295.

Silver, Brian. ‘On the Adab of musicians’ in Moral Conduct and Authority: The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam, ed. Barbara Daly Metcalf, pp. 315–329. Berkeley; London: University of California Press, 1984.