Lucy Dearn has recently completed an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award project with the Sheffield Performer and Audience Research Centre (SPARC) at the University of Sheffield under the supervision of Professor Stephanie Pitts. She has been working in partnership with chamber music promoter Music in the Round to conduct research with classical music audiences across South Yorkshire. Her research investigates community formation around a concert series and the views of younger people often underrepresented in the regular makeup of audiences.

Jonathan Gross is based in the Department of Culture, Media and Creative Industries at King’s College London, working on the Get Creative Research Project as part of the BBC-led Get Creative campaign. He previously worked on collaborative research projects at the Universities of Leeds and Liverpool, and at the Sheffield Performer and Audience Research Centre. His PhD was an ethnography of audiences at the BBC Proms, which he completed at The London Consortium.

Sarah Price is a postdoctoral research associate on the Sheffield Performer and Audience Research Centre’s new project, Understanding Audiences for the Contemporary Arts. Prior to this, she was a postdoctoral researcher at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance and completed an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award project with SPARC and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Her research interests are in audience development, the value of cultural experiences for individuals who engage with the arts, and the role of academic research within the commercial arts industry.

Stephanie Pitts is Professor of Music Education and currently Head of Music at the University of Sheffield and Director of the Sheffield Performer and Audience Research Centre. She has research interests in life-long musical engagement, including amateur musical performance and live music listening. She is the author of Valuing Musical Participation (Ashgate, 2005), Chances and Choices: Exploring the Impact of Music Education (Oxford, 2012) and, with Karen Burland, a jointly edited book on audience experience, Coughing and Clapping (Ashgate, 2014).

Abstract

Drawing on studies with audiences in three different cities and across multiple genres, this chapter considers the contribution of empirical research to understanding the experience of live music listening. We evaluate the potential of qualitative research tools ranging from life history interviews to art-informed visual methods, and present some of the findings from our recent work, which highlights the interconnectedness of the personal, social and musical elements of listening experience. Conclusions are drawn about the usefulness of these approaches for arts organisations, academic researchers and audience members themselves.

Introduction

Understanding how and why people listen is a central aim of the Listening Experience Database (LED) project, which has taken a mainly archival approach to documenting experiences with live music across a wide range of settings and centuries. Interpreting the call for evidence from ‘any historical period’ to include ‘now’, the work of Sheffield Performer and Audience Research Centre makes a distinctive contribution to LED by considering how orchestral concerts, chamber music and contemporary classical music are experienced by their audiences, by asking: who attends and who does not?; how is live listening experienced musically, personally and socially?; and what are the challenges for researchers in understanding what people do when they listen?

Research with today’s audiences, rather than their historical counterparts, brings some advantages in being able to ask people about their motivations and experiences. However, other challenges are the same across the decades and centuries, most notably in the difficulties for audience members of finding the language to explain and evaluate their listening experiences. Audience research takes many forms1 and has shown in recent years an increasing awareness of the limitations of talk-based, retrospective reporting of the live arts experience, turning to visual methods,2 digital technology3 and social media4 in the attempt to capture the immediate impact of being in an audience. The longer-term impact of concert listening is of significance too, and life history approaches that take account of past arts experience and learning are also contributing to the debate.5 Understanding audience experience has obvious benefits for arts organisations, for whom the additional insight on how and why their audiences attend is of value in increasing access, growing and sustaining audiences, and building community. For academic research, greater understanding of how music intersects with people’s lives is also valuable, bringing fresh perspectives on cultural engagement, social interaction and ‘ways of listening’.6

In this chapter, we draw on our ongoing collaborations with Birmingham Contemporary Music Group (BCMG), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO) and Music in the Round (MitR), using empirical findings to explore the varieties of listening experiences among regular audiences and new attenders in those settings. We show how, through the use of a range of qualitative methods, researchers can investigate the hopes, anxieties and expectations that today’s audiences bring to the concert hall, and we consider the usefulness of eliciting and understanding these perspectives, as a way of enriching and sustaining audience experience. Each section of the chapter focuses on one of our recent studies, indicating the methods we have employed to study live listening experiences in the concert hall today, and illustrating the kinds of insight that these approaches can help generate.

Beyond language: the ‘Write-Draw-Tell’ method

When making empirical enquiries into classical music audiences, it is vital to question how such an ephemeral listening experience may come to be understood by researchers. In recent years, there has been a move from the demographic segmentation of audiences towards a deeper understanding of their lived experience, which prompts the need for a further investigation into how current methodological toolkits may be advanced in this field.

Empirical studies have begun to explore classical music audiences using quantitative methods, underpinned by a theoretical framework which investigates experience and is not limited to demographics.7 These studies questioned audience members before and after the event; however, participants were not able to reflect on the experience as it was happening. Other studies that consider classical music audiences have used more qualitative, talk-based research methods.8 Nevertheless, despite a growing body of data gathered with audiences, current qualitative methods used in this field are not without limitations and could be developed further.

A key consideration when using talk-based methods with audiences is the frequency with which commercial organisations request demographic information and ‘audience feedback’. This may result in greater familiarity with such research questions and standardisation of responses, resulting in a risk that participants may have become over-‘sociologised’ in qualitative methods.9 Another issue highlighted in the field is the way participants are often asked to reflect retrospectively, away from the listening experience, and therefore can be ‘influenced by partial memory, cognitive filters such as selective memory and peer pressure’.10 It could be the case, therefore, that researchers are not able to ‘entirely rely on oral or written accounts of the audience’s experience to provide a whole picture of this experience’.11 Finally, the level of literacy and technical language available to audience members when describing an arts experience, particularly when researching with newcomers or younger attenders, can greatly affect individuals’ confidence and ability to respond to the questions they are asked.

Lucy Dearn’s research at Music in the Round has focused on developing new methods for understanding the audience experience. Considering the issues outlined above, Dearn has applied a method termed ‘Write-Draw-Tell’ to the study of listening experiences of regular and new audiences. This method translates well across varying age ranges and attendance levels, is unfamiliar, sanctions participants to give an instant response simultaneously with their listening and allows participants to use some form of non-verbal response when describing the concert experience.

The art-informed creative method ‘Write-Draw’ has its origins in children’s health education.12 The method was developed to allow children to feel a greater sense of involvement and ownership in research investigating their use of health services. The method is based on provoking a written and drawn response to a research question. Later developments of this method have also introduced a ‘Tell’ phase, which encourages participants to explain the verbal and visual elements they have produced becoming a metaphor for discussion, often about sensitive or conceptual topics.13

The use of creative methods to study arts audiences is not without precedent; ethnomusicology and more recent applications in audience studies have used verbal or visual elements.14 Matthew Reason uses drawing and discussion-based methods when investigating primary school children’s experience of live theatre,15 and the development of a non-verbal methodological toolkit has been used with art gallery visitors in research by Lisa Baxter et al. 16 Bonita Kolb’s study investigating young people’s first attendance of a classical music concert also uses some visual activities as part of the pre- and post-concert focus groups.17 However, in Kolb and Baxter’s research these visual artefacts are not analysed as part of their studies and are used solely as a stimulus for discussion. Hence, the application of an arts-informed method like Write-Draw-Tell to classical music audiences, particularly simultaneously with the performance, is a new addition to the methodological toolkit currently used with arts audiences.

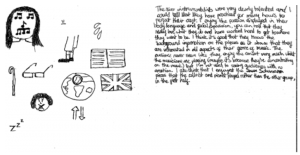

Presented below are two brief examples of the data collected using the Write-Draw-Tell method with newcomers under the age of 25 and regular audience members. The first response is by a 15-year-old female of Black Caribbean ethnic origin who is new to classical music concert attendance.

The written response suggests this newcomer was lacking visual clues from other audience members as to how to listen and react to this type of music. A strong sense of ‘still and silent listening’18 was shown through the drawn responses, signifying that for this participant the idea of not being able to communicate with others during the concert was uncomfortable or confusing. A sense of alienation is also seen through this Write-Draw card. Firstly, a disparity between the age of this listener and the age of others in the audience is highlighted. Ideas of nationality are also present, with a strong sense of British nationalism seen through the drawn response, despite the programme for this concert not including any British composers. During the ‘Tell’ phase the participant was not sure why she had drawn these symbols, stating: ‘I don’t really listen to this type of music; I just thought it was really British’.

The second example is representative of the responses of regular audience members.

Many of the drawn responses by adult members were far more fluid than the fragmented replies from under 25s. They also relied more heavily on literal representations of the players, rather than abstract or metaphorical drawings. The written side often included musical terms but was also used by regular audience members to give feedback to the arts organisation, for example, the programming choices of the arts organisation, seen through the statement that Ligeti is ‘not really chamber music’ according to this audience member.

Although the application of this method to the study of classical music audiences yielded new insights, in particular an instant non-verbal response to concerts, it also brought its own challenges: firstly, distraction and an alteration of the arts experience; secondly, a degree of participant reluctance to make use of the method; and thirdly, the lack of established analytical frameworks to use when handling visual data.

Beyond the present: the life history approach

Among the many methodological challenges that face the study of listening, perhaps the most intractable is the problem of how to study experiences that are ‘beyond’ language. As the previous section illustrated, the innovative use of drawing techniques suggests new possibilities here. More conventionally, it is of course possible to study listening through the laboratory methods of experimental psychology. But as Clarke, Dibben and Pitts point out, one of the major drawbacks of experimental approaches is their disregard for the (often highly consequential) social environments in which musical listening takes place.19

As previous studies have shown, the value of even the most rarefied and seemingly ‘interior’ modes of listening – such as the still and silent attention of the classical concert hall – need to be understood within the contexts of everyday life.20 In studying the individual or personal value of concert hall listening today, we need to examine this value within both synchronic and diachronic contexts. In other words, we need to address both the immediate social environments in which the listening takes place, and the accumulated experience and attitudes developed over the course of each listener’s lifetime – aspects of biography that constitute key contexts to the value that audiences’ listening experiences have for them.

These points can be illustrated through a recent research project conducted by Jonathan Gross and Stephanie Pitts in collaboration with a range of organisations presenting contemporary arts in Birmingham. Our work in Birmingham was initiated by the marketing manager of Birmingham Contemporary Music Group (BCMG), Tim Rushby, seeking to know if there are current and potential cross-overs between audiences for ‘contemporary’ arts across art form (contemporary craft, dance, music, theatre and visual arts).21 In order to address this overarching issue, Gross and Pitts established a series of research questions concerning the experiences audiences have of the contemporary arts: these focused on routes into the contemporary arts, facilitative conditions for audience engagement, and cross-arts experiences of access and engagement.

To address these questions, Gross and Pitts made use of a combination of ethnography, an ‘audience exchange’ method of group conversation, and a biographical or life-history approach to semi-structured interviews. Ethnography, or participant observation, is the anthropological method of studying a practice or people through spending time with them and joining in. This is a particularly valuable way of examining the synchronic contexts of listening. For example, we were able to attend BCMG concerts and rehearsals with members of the audience, speak with them in the immediate surroundings of the musical event, and invite them to reflect informally on their present experiences, while observing audience behaviours and the uses made of the auditorium and foyer spaces.

Our second method, the audience exchange, involved research participants signing up to attend a performance or exhibition at a venue (or art form) they would not typically go to. In groups of between six and ten, we attended the performance or exhibition together, and then had a semi-structured conversation about our experiences of the show.22 Audience exchange participants spoke often of the usefulness of these conversations for enriching their experience of the live arts event, allowing them to hear other people’s responses to sometimes challenging or confusing work, and to explore their own responses by considering and articulating them in the group discussion. Within the subsequent 2015/16 and 2016/17 seasons, BCMG have programmed audience exchange conversations after four of their concerts, each chaired by Jonathan Gross. BCMG’s decision to respond to the research project in this way indicates the potential value of the audience exchange method not only as a way of more fully understanding listening experiences, but as an enjoyable activity embedded within the creative programme of arts organisation on an ongoing basis.

Beyond the group setting of the audience exchange method, the one-to-one life-history interview provides a particularly powerful opportunity to dig deeper into audience experience. Life-history interviews have been employed within sociology since the 1930s,23 and yet, despite the recent ‘biographical turn’ observed in the social sciences,24 there is still little use of this type of interview method to study audiences. One important reason for this may be the fact that conducting interviews in this way is time intensive (for interviewer and interviewee); it produces very rich qualitative data that requires complex and time-consuming analysis; and requires particular research expertise and resources that many arts and cultural organisations do not have at their disposal. But, as our work with BCMG shows, the use of life-history interviews has the potential not only to illuminate the personal value of listening experiences, but to thereby help inform how musical institutions might develop new and deeper relationships with their audiences.

The specific version of semi-structured interviews that Gross has developed in his work with audiences is carefully designed to address the value of listening experiences within the biographical contexts of each interviewee. A combination of very open questions (such as ‘tell me about the last concert you went to’) and very targeted questions (‘how did you hear about this concert?’) provide opportunities for interviewees to articulate their listening experiences in their own terms, while ensuring that the conversations address specific points of interest for the research. Opportunities are also provided to answer questions more than once (‘is there anything else you’d like to tell me about the last concert you went to?’). This allows participants to think out loud and so provides opportunities – and a sense of permission – to go beyond the most readily available vocabulary. This can result in a richer, more personal account of listening experiences and their value to individuals, thereby addressing (at least partially) some of the challenges of mediating listening experiences through language, noted as a limitation in earlier research.

Another distinguishing feature of Jonathan Gross’s approach to interviewing is the use of an explicitly biographical framework, which, again, combines very open and more targeted questions: giving interviewees the opportunity to articulate their listening experiences – and the value of these – in relation to any other part of their life they choose to, including work, family, friendship, education or any other aspect of everyday life. Questions include, for example, ‘how have your interests changed over the course of your life?’, ‘tell me about your school’ and ‘what jobs have you done?’ These are asked alongside more targeted questions, such as ‘when did you first attend a concert?’ and ‘how has your concert going changed over the course of your life?’

To give just some indication of the kinds of findings this approach can generate, we offer the example of Dave (not his real name), a teacher in his 40s and a regular audience member at BCMG. Dave explains that his principal passion is twentieth-century classical music. He first became interested when hearing a piece on television as a child, and then sought out more by listening to BBC Radio 3. Teaching himself about music in this way, he first started going to orchestral concerts as a teenager, and was always very comfortable attending on his own or with others. Since that time, he has listened to a large amount of twentieth- and twenty-first century classical music. Dave normally attends several performances each week, and at times this can be as many as five events – spanning contemporary music, opera, dance and film. He explains the central place that attending live contemporary arts has for him, saying ‘this is what I do’.

Dave describes missing the sense of ‘difficulty’ he first experienced when listening to contemporary classical music as a child. He liked that difficulty – and the pleasures he found in struggling with strange and new ‘sound worlds’. He no longer experiences difficulty in this same way – but continues to take great pleasure in the ephemerality of the new music he is hearing. In combination with his employment as a teacher, attending the contemporary arts is how Dave lives his everyday life. He describes the experience of attending midweek, having just seen a brilliant performance, sitting waiting for the post-show talk to begin, and thinking to himself ‘this is the life’. Attending the contemporary arts is a central activity for Dave, and a key source of enjoyment and satisfaction. He particularly enjoys opportunities to attend pre- and post-concert talks, and to feel ‘part of that world’.

Dave’s example illustrates the capacity of this approach to open up the value of listening experiences within the broad contexts of people’s lives. If musical experience is well-recognised to be enmeshed with biographical memory,25 there is much more scope to investigate the ways in which the complexities of our lives are active within the present of listening and its value.

Beyond the individual: qualitative interviews and social experience

The qualitative methods employed by SPARC researchers in these projects offer a deep understanding of an individual’s engagement with classical music. The data produced by these methods is often highly complex and can even contradict itself. This can be difficult to reconcile with research conducted within the arts industry.26 Commercial research is heavily reliant on quantitative data, both collected through questionnaires and data gathered from ticket sales transactions. Although there is a long history of qualitative focus groups in market research, they are often conducted to address specific business decisions, and are rarely as open-ended and exploratory as the research conducted by the SPARC team.27

In her doctoral research at the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Sarah Price has conducted semi-structured interviews with audiences at a range of different concerts and across various levels of engagement. These interviews aimed to understand how audiences choose the concerts they attend and their experience in the concert hall, and asked them to reflect on how they perceived themselves as listeners. Price has also worked closely with the marketing team to analyse their extensive customer database and ticket sales history. She has had first-hand experience in how in-depth qualitative methods can complement quantitative data analysis in helping arts organisations better understand their audiences.

One way in which qualitative methods go beyond the reach of booking data is in understanding the role of companions. Ticket transactions data only captures information about the person who physically bought the tickets, the ‘initiator’ in Alan Brown’s model.28 This leaves a ‘ghost audience’ with whom arts organisations have no contact, despite the potential for them to be regular, highly-engaged attenders. Price’s interviews at the CBSO draw attention not only to the variety of companions that initiators bring to concerts, but also the many ways in which these companions can influence their choice of concert. Whether an audience member regularly attends with the same person, has an occasional companion, or attends alone, can be as important as aesthetic factors for selecting a concert to attend.

Regular companions

Some interviewees had a companion with whom they regularly attended concerts. This was often married couples who regularly attended with their husband or wife, though there were examples of friends and family members being regular companions. Yvonne29 is a regular CBSO attender who always goes to concerts with her husband. They have been attending CBSO’s core classical concerts since Yvonne retired a few years ago. Yvonne’s husband is rather more conservative in his musical tastes and therefore she admits to ‘manoeuvring the paperwork’ to hear music she likes. During the interview, Yvonne realised that the CBSO were playing Britten’s War Requiem at the BBC Proms that same evening:

Yvonne: Oh it’s today! Don’t remind me! I did want to go because it was… we went to Coventry to hear the War Requiem and I was just blown away by it but you see [her husband] wasn’t that keen and I thought ‘he’s not going to like going down to hear it again’. And we probably would have had to book a hotel when we got back as well so it would have turned into an expensive trip but I would have liked to have done it. Perhaps next year.

Yvonne was clearly disappointed not to be going. Having been ‘blown away’ by the Requiem the first time, she was keen to see it again. Her husband, however, was not impressed and therefore she assumed that he would not want to travel to London to hear it again.

Yvonne and her husband are classic examples of Brown’s ‘initiators’ and ‘responders’.30 Yvonne, the initiator, finds concerts to attend and pitches them to her husband, the responder. Developing Brown’s model, Dearn and Price have shown through their combined research data that initiators are often more adventurous in their musical tastes than responders, but that responders’ conservatism can mean they have the final say.31 Yvonne pushes her husband outside his comfort zone by taking him to concerts that he would not ordinarily want to attend. However, in always wanting to attend with her husband, Yvonne limits herself to concerts she can persuade him to attend and on some occasions, as with the War Requiem, misses out.

While Yvonne’s complete attendance history is recorded on the CBSO customer database, the organisation has no record of her husband’s attendance, despite him regularly going to CBSO concerts. In addition, bookings data cannot capture the effect of their different tastes on their choice of concerts. Qualitative investigation is necessary to expose the impact of socialising on concert selection.

Occasional companions

Audiences who are willing to go alone or who have a variety of companions are of course less likely to miss out because of the tastes of companions. However, the desire to share concerts with friends and family means that companions still influence their concert choice. Nicola is a very frequent attender, going to around 40 CBSO concerts a year and more besides at other organisations. She is more than happy to go alone, but tries to find concerts that her friends would enjoy:

Nicola: I go [to concerts] with different people. Some friends won’t try much beyond Beethoven and Mozart (oh, how they do miss out!) and some will try everything and anything, if they’re available to do so. Some only like Friday Night Classics too. Some will only go to CBSO or other symphony orchestras; others prefer chamber music. Some will only go to the opera in concert ones. So, since I love lots, it is about finding the right person for each particular concert – and sometimes nagging them to try something outside their comfort zones.

Nicola ‘loves lots’ of different types of classical music and so is able to find concerts to suit the tastes of a number of friends. Like Yvonne, Nicola is an initiator. She has broader tastes than her responders and consequently tries to push her companions to try new things. Unlike Yvonne, however, Nicola is willing to attend alone and therefore is not restricted by the tastes of her companions. Finding concerts for companions is Nicola’s way of sharing the concert experience. Most participants looked for opportunities to share concerts with companions and would only attend alone when no-one was available or interested. Despite the sacrifices being made for companions, no participants said that they would rather attend alone. Attending with other people seems to add social value to a concert which can be more important than the aesthetic engagement.

Attending alone

The small number of participants who frequently attended concerts alone reported talking to other audience members. Trevor is a long-term subscriber at the CBSO. He talks to ‘all sorts of people’ at concerts and describes concerts as a ‘social event’. Trevor’s subscription allows him to sit in the same seat for every concert and consequently he has become friends with attenders in the surrounding seats:

Trevor: There’s a guy that sits next to me on my left and he’s extremely knowledgeable about music. […] He’s enhanced my knowledge of music quite a lot. […] He’s very good at explaining what’s happening, you know. […] I know he’s a very keen Bruckner fan, and if it’s a Bruckner symphony, he’ll tell me all about it. I don’t read the programme [because] he’ll tell me all about it.

Over many years of attendance, Trevor has become friends with other audience members. The value of friendships and ‘like-mindedness’ to creating a sense of audience community has also been found in research at Music in the Round by Stephanie Pitts and Chris Spencer.32 As Ruth, another CBSO audience member, described it: ‘I’m not very good at chit-chat [but] when you’re meeting people here, you know you’ve got something in common to talk about’. Because these friendships are based on a mutual interest, they can also be a source of learning about classical music. Trevor will draw on his neighbour’s knowledge of Bruckner rather than buying a concert programme. The conversations he has with his fellow audience members shape the way he listens to the music. Therefore, whether or not these social interactions influence his concert choice, they certainly impact on his concert experience.

At the end of the interview, Trevor expressed how much he had enjoyed taking part in the research:

Trevor: It’s lovely to talk to someone about classical music! Because I’m afraid in the circles that I mix in, so very few … I’ve got nobody to talk to! […] There is nobody else, it’s sad! And that’s why I think socially, here, it’s good to be able to talk.

Despite regularly talking to other audience members at concerts, Trevor still wishes he was able to have more conversations about classical music. His comment highlights how much audiences want to talk about what they have heard. The real value of socialising, and the reason why audiences are willing to compromise on their choice of concerts in order to bring companions, is that it allows attenders to discuss and reflect on their concert experiences.

Semi-structured interviews offer new insight into how the social context of listening influences concert selection. Talking to participants for around thirty minutes each allowed them time to consider all the factors that went into their decision to attend. In addition, as in Jonathan Gross’s life-history interviews, participants were asked about their route into classical music attendance, whether they participate in music, and their engagement with other cultural events. Throughout the conversation, participants would return to the question of ‘how do you decide which concerts to attend?’ They provided examples to prove their points, clarified earlier responses, and described anomalies in their decision making. Yvonne, Nicola and Trevor’s comments begin to reveal the complexities of the decision to attend and the importance of social interactions in shaping concert attendance.

Conclusion

Our illustrations of work with audiences at Music in the Round (MitR), Birmingham Contemporary Music Group (BCMG), and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO) have highlighted the diversity of empirical methods used within the Sheffield Performer and Audience Research Centre to explore the personal, social and musical value of live arts listening. In each of our studies, our chosen methods involve exploring ‘listening experience’ in its many facets – from the decision to attend a particular event, the ways of listening and engaging in the moment, and the process of articulating and reflecting on that event and its relationship to other aspects of the listener’s life. No single method achieves a perfect understanding of the listening experience, but by employing and exploring different methods, and by encouraging in all of them a reflexive approach, in which the listeners themselves grapple with the challenges of articulating and interrogating their responses, we come closer to having a sense of what it means to listen as part of an audience.

The research presented by each of the four authors in this chapter involves close collaboration with arts organisations. Dearn and Price’s three-year associations with MitR and CBSO, respectively, have each been enabled through AHRC collaborative doctoral awards; while Gross and Pitts’ work with BCMG came about through an invitation from BCMG to extend Pitts’ past work with classical music audiences to the different contexts of attenders at contemporary arts events. Such close associations are mutually valuable to arts organisations and researchers, bridging some the historical divides between commercial and academic research,33 and prioritising research questions that can not only increase understanding of audience experience, but also affect positive change. We have been fortunate in that our partner organisations have shared our interests in the complexities of audience experience, not looking for the quick answers of how to increase ticket sales or repeat attendance (though those suggestions have been welcome, where we have found them), but instead welcoming the insight that rich, qualitative research can offer on how and why newcomers and regular attenders are drawn to live listening and encouraged to return.

Our headline findings show that the personal, social and musical aspects of concert listening experiences are inextricably linked – and this has implications for the potential value of qualitative research methods of the kinds presented in this chapter. Even when it comes to deeply personal or private listening experiences, the opportunity to reflect on these through conversation (including conversations initiated by researchers) helps to embed, articulate and understand the experience in ways that have the potential to influence research participants’ future patterns of engagement and experience, including, potentially, an expanded receptiveness to a wider range of musical activities and experiences. In turn, these conversations can inform the future development of organisational practice – suggesting new ways in which musical institutions can respond to how the personal value of concert listening can be enabled, thereby developing relationships with audiences, contributing to and building new, valuable listening experiences through innovative concert practices.

We have aimed in this chapter to show the value of empirical methods for understanding listening experience, and have welcomed the opportunity to set this alongside the archival approaches of the Listening Experience Database to prompt interdisciplinary discussion of the ways in which listeners talk, write and think about their live arts engagement. There is scope for the questions at the forefront of our research to be applied to the historical evidence of the LED: analysis, for example, of the topics addressed by Samuel Pepys as he wrote his diary entries on the cultural life of seventeenth-century London would demonstrate that the effects of venue, the presence of other listeners and the expectations drawn from prior arts engagement have shaped audience experience over many centuries. Empirical research with arts organisations offers the chance for an understanding of audience experience to shape the cultural life of future generations, and will need to remain responsive to changes in technology, private listening habits and educational change. Through the use of multiple, flexible research methods, understanding of the many factors involved in listening experience can continue to grow, and with it the ability for researchers and arts organisations alike to articulate the value of live listening in the contemporary world.

Select bibliography

Baxter, Lisa. ‘From luxury to necessity: the changing role of qualitative research in the arts’, in O’Reilly, Daragh and Kerrigan, Finola (eds) Marketing the Arts: A Fresh Approach. Abingdon: Routledge, 2010, pp. 121–140.

Burland, Karen and Pitts, Stephanie (eds). Coughing and Clapping: Investigating Audience Experience. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014.

Dearn, Lucy, K. and Price, Sarah M. ‘Sharing music: social and communal aspects of concert-going’, Networking Knowledge, 9(2), 2016, pp. 1–20.

Gross, Jonathan and Pitts, Stephanie. ‘Audiences for the contemporary arts: exploring varieties of participation across art forms in Birmingham, UK’, Participations, 13(1), 2016, pp. 4–23, http://www.participations.org/Volume%2013/Issue%201/2.pdf, accessed 9 April 2017.

Price, Sarah M. ‘Academic and commercial research: bridging the gap’, Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 12(2), 2015, pp. 168–173, http://www.participations.org/Volume%2012/Issue%202/9.pdf, accessed 9 April 2017.

Radbourne, Jennifer, Glow, Hilary and Johanson, Katya (eds). The Audience Experience: A Critical Analysis of Audiences in the Performing Arts. Bristol: Intellect, 2013.

You must be logged in to post a comment.