Robert Fraser is Professor Emeritus of English in The Open University, having previously taught at the Universities of London, Cambridge and Leeds, and at the University of Cape Coast in Ghana. He is a performed playwright, and has published over twenty books, several of them on the literature of Africa. In his youth he was a chorister at Winchester Cathedral, and he subsequently studied Harmony, Counterpoint and Composition at Morley College in London. He has had several of his compositions performed, and for three years was a Co-investigator of The Listening Experience Database (LED).

Abstract

One of the salient factors in the musical history of the late twentieth century was a radical relocation of the multiple distinction between listening, performing and composing. A personal encounter with Steve Reich in Ghana in the summer of 1970 acquainted the author with one aspect of this shift. Reich was in Africa to study the drumming traditions of the Ewe people, whose music had been the subject of an influential monograph by the ethnomusicologist A. M. Jones (1889–1980). The following year saw the first performance in New York of Reich’s work Drumming for nine percussionists and two sopranos. Through a comparison of Jones’ field recordings with his and Reich’s transcriptions, and an analysis of the score and successive recordings of Drumming, I examine the processes of Reich’s listening, and the ways in which he absorbed and transformed certain elements in African music. After a brief look at works by Georgio Ligeti influenced by Africa and Reich, I conclude with some remarks about the ramifications of this revolution for recent musical history.

Introduction

The tripartite, yet complementary, relationship in Western art music between composer, performer and listener depends upon a comparatively stable understanding of these terms and agencies. Of course, the distinctions have never been absolute. All composers listen, to their own work as well as that of others, and so do all performers: to themselves and, in an orchestra or other ensemble, to those around them. When running through a piece of music in my mind – the activity sometimes known as ‘chant intérieure’ or ‘haunting’1 – I could be said in some sense to be performing it; if I alter it in the least (say, by misremembering it) I could also be said to be acting as a part-composer.

There are, however, limitations to these elisions. In a classical concert hall the audience occupies the stalls, boxes and galleries and, in so doing, identifies itself as a body of passive listeners. Interventions by them are for the most part unwelcome, except by means of the ritualistic response of applause and, even then, the etiquette surrounding such expressions of approval – its timing, length and disposal within an individual piece (should we clap between movements?) – has shifted over time, and has been the subject of sometimes heated debate. Expressions of disapproval are not encouraged, nor are bouts of coughing and the accidental sounding of mobile phones, against which dire strictures are habitually announced before each concert. The temporary lifting of some of these restrictions, for example at the Last Night of the Proms, is remarkable for its rarity; indeed, the euphoria greeting that annual exception in the British music calendar may well be the expression of relief at the relaxation of otherwise sacrosanct rules.

Correspondingly, the term ‘orchestra’ derives from the ancient Greek word for the space in which the action of the drama took place; its occupation by a group of musicians identifies them as an active body of performers. If, at the end of the performance, the composer steps forward and takes a bow, he or she is thereby identified as the intellectual progenitor of the music just heard.

In his chapter on listening practice in the English provinces during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, David Rowland has called our attention to important exceptions to this rule. Drawing on the word of James Johnson and others, he has noted the gradual emergence at the time of what Johnson has termed ‘absorbed’, as distinct from ‘inattentive’ listening. That said, it remains a fact that, by the beginning of the twentieth century, audience members were by and large assumed to be passive recipients of a pre-composed piece. Yet medieval music had not operated in this way, and neither does most folk music. Most significantly for our purposes here, a thoroughgoing revolution in the dynamic between our three classic capacities since the late 1960s has transformed our expectations of certain kinds of musical event. In the closing decades of the twentieth century the boundaries between composing, performance and listening moved dramatically, invading one another as seldom before. As a result, in musicological parlance, the traditional verbs ‘to compose’, ‘to perform’ and ‘to listen’ have lost ground before the comprehensive gerund ‘musicking’.2 Within this fundamental re-orientation are ranged a set of subservient changes. The making and reception of music have over the last half century opened out in several directions at once. Improvised music, which learned much technically from jazz, and musical minimalism are just two of these trajectories. As we shall soon see, they are not entirely consistent with one another.

In the chapter that follows, I identify one of these seminal shifts at a certain moment in time, of which I was an accidental witness: not as composer, performer or primarily as listener (though I have been all three), but as discussant. I begin with an anecdote or moment of recall – a testimony involving Steve Reich, Africa and drumming, then pass on to consider the implications of that instant in time before turning to certain facets of Reich’s influence. I end by returning to the aesthetic and musicological considerations with which I began.

1970: Ex Africa Semper Aliquid Novi

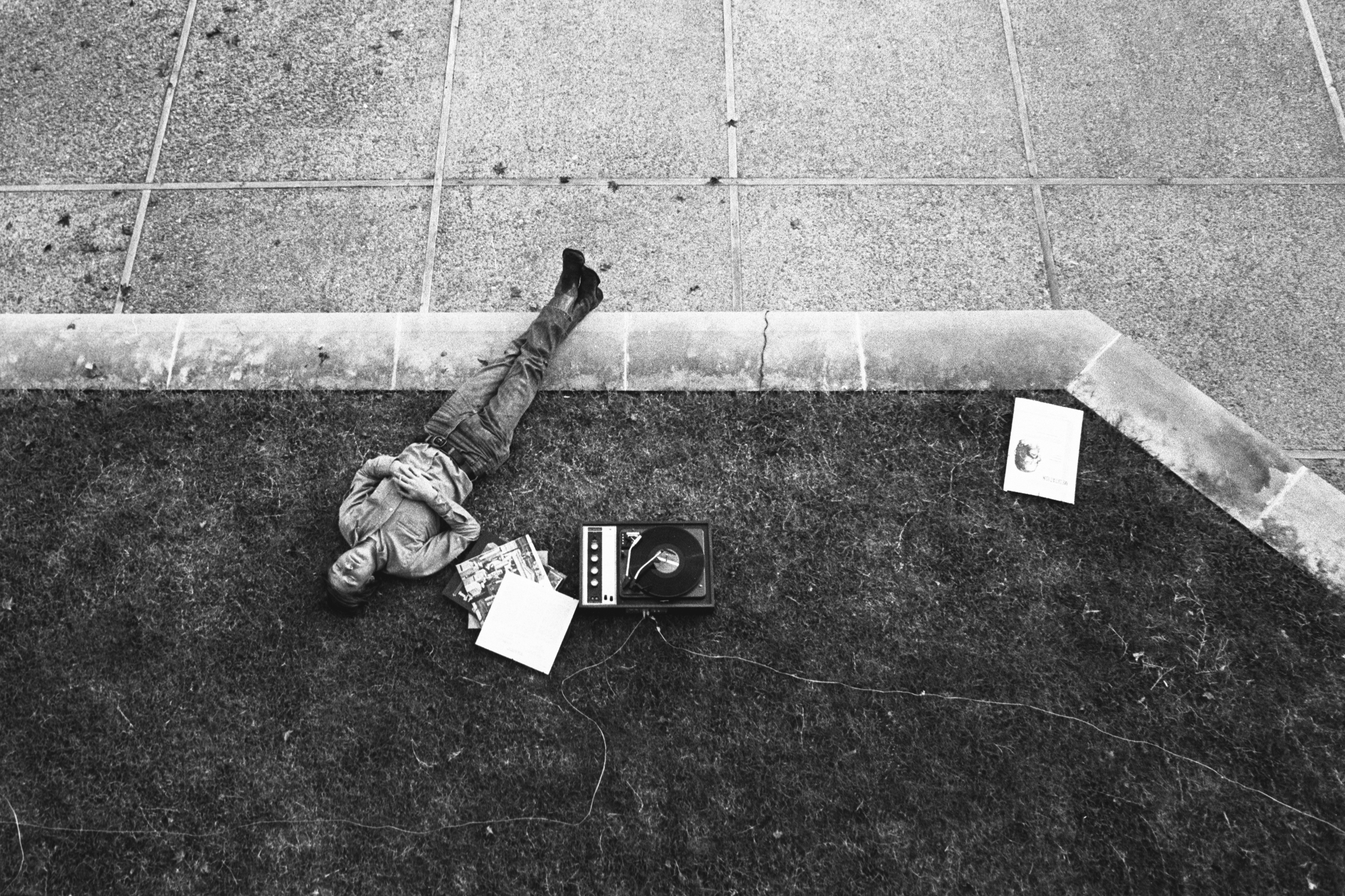

It was a solitary August for me: the dead vast and middle of the long vocation at the end of the first year of my first job, lecturing at a small, recently-founded university college by the seaside in Ghana. So one afternoon I climbed into my second-hand Volkswagen Beetle and drove the 100 odd miles down the coast to the swankier national university, situated at Legon, about seven miles to the North of the capital, Accra. That evening I entered its staff club, empty save for a lone figure, an American in his late 30s wearing a baseball cap, and hunched over his beer by the bar. I approached and asked how he was. Rather queasy, he told me. I asked him what he did, and he told me he was a musician. Then he asked me how I was spending the hols. I told him that I had formed a drama group of young people in the housing estate where I lived near Cape Coast to perform Vulture, Vulture, a ‘Rhythm Play’ by the local playwright Efua Sutherland,3 for which purpose I had acquired a goat skin from the village butcher, and had it shaved and stretched on a wooden rectangle by the neighbourhood carpenter to create a frame drum that, 47 years later, I still possess. That’s interesting, he said, because he was in Africa to study drumming, so for two hours we drank and ranged in conversation over his specialism, music, and mine, poetry. He seemed very interested in the rhythms of both. After six or seven beers, I rose to my feet and said ‘It has been a great pleasure, but I must go now. My name is Robert Fraser.’ ‘Mine’, he replied, extending his hand, ‘is Steve Reich.’

I had no idea that I was talking to a world-famous composer, for the perfectly good reason that he wasn’t. In 1970 few music lovers had heard of Reich beyond a tiny Manhattan avant-garde. This situation didn’t last for long. His queaziness was malaria; after a further couple of weeks he returned to New York, where the following year he created Drumming, first performed at the Museum of Modern Art on 3 December 1971. It is a work that, by Reich’s own admission, draws on his listening and studying in Ghana. It is the connection between the listening and the studying, and the subsequent composition and performance, that I am concerned with here, and the first step is to recognise that all of these relate to a very particular local tradition.

A. M. Jones, as ethnomusicologist and influence

The Ewe people, about six million strong, straddle the border between eastern Ghana and the neighbouring territory of Togo. It was at the feet of an Ewe master drummer, Gideon Alorwoyie, Master Drummer of the Ghana National Dance Ensemble, that Reich had come to study. No wonder he seemed interested in affinities between poetry and music, since the Ewe scarcely distinguish between them: one single word ‘heno’ serving for both their singers and their poets. The most distinguished cantor of the period was Vinoko Akpalu (1878–1974), then 92, of whom several of my own students were keen admirers, and who always performed with a drumming ensemble. Two decades previously, his art and those of his fellow recitalists had been studied by the British missionary and ethnomusicologist Arthur Morris Jones (1889–1980), who had brought out a two-volume account of his researches, entitled Studies in African Music in 1959, ‘addressed in the first place to musicians’.4 Eleven years later, ethnomusicology was yet to enter the American conservatoire to any significant extent. There were important exceptions since, as Philip Glass remarks in his 2015 memoir Words Without Music, Jones’ book had been in the library of the Julliard School in the mid-1960s, when both he and Reich had studied there.5

Jones is obviously a pivotal figure in the story, so it is as well to spend a while thinking about his ideas. A seminal figure in the history of African musicology, his conceptions – his ways of thinking about the rhythmic dimension in music in particular – have spread way beyond that regional field. Born in 1889, he was an Oxford theology graduate who, after ordination, had taken a teaching diploma and then spent 29 years as a teacher and missionary in what is now Zambia, 21 of them (1929–50) as Principal of St Mark’s College, Mapanza.6 On resigning from this post he had taken up a lectureship in African music at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in the University of London, from which he had retired in 1966. It was in London that Jones seriously applied himself to the study of Ghanaian percussive music, with the assistance of the Ewe drummer Desmond K. Tay.

In 1959, the same year as the publication of his book, Jones had recorded a series of programmes for the BBC Transcription Service, in which he had set out, perhaps for the first time, an all-embracing African musicology.7 In melody he had noted the prevalence of fourths, and in harmony the habit of organum. Rhythm, though, was the core of the tradition. To account for it, he had already coined the term ‘cross-rhythm’, now a stock in trade of musical analysis but then quite new: a phenomenon which he had carefully distinguished from mere syncopation.8 African music, he asserted, possessed an ‘intoxicating rhythmic harmony’, demanding to hear and very hard to transcribe. Its salient quality was that, in African rhythmic polyphony, the down-beats of the various parts did not coincide. Instead, they played against one another, obliging the listener’s mind to work on several levels simultaneously. Such effects were the rule; percussive coincidence, when and where it occurred, was an incidental effect of no structural significance. ‘With Western music’, he had generalised in his book, ‘deliberate synchrony is the norm from which our music develops…If our suggestion has any truth, then the African also uses synchrony of pattern, but in a much more subtle way. His norm is the cross-rhythm, and the synchrony is derivative.’9 The result, he concluded, ‘is a principle which our Western musicians are yet to exploit.’ Was this an invitation?

Making sense of cross-rhythms

Jones’ book abounds in transcriptions of Ewe music set out in full score. In 1971 he was 82, and had long retired from teaching at SOAS where, in the year of the composition of Drumming, Reich visited him. It seems fairly likely that, on this occasion, Jones played some of his recordings back to him; they are now kept in the National Sound Archive in the British Library. If we want to understand the way Reich heard African music, we have to bear in mind the transcriptions in Jones’ book, his original recordings and Reich’s own exposure during those brief weeks when I met him.

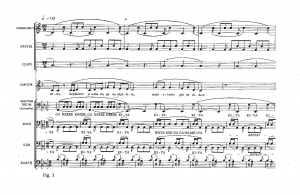

Here is a transcription of the Ewe Nyayito funeral dance from Jones’ Studies in African Music, as reproduced from my own book West African Poetry of 1986.10

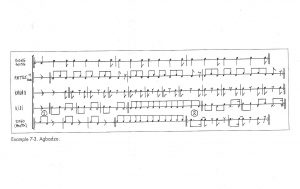

And here for comparison is Reich’s own transcription of the Ewe Agbaza dance, first published in 1972.11

It is quite evident, even at a glance, that the line-up of percussion is very similar, and that neither have uniform bar-lines because, as Reich himself remarks, Ewe music has no unitary down-beats, consisting as it does of the superimposition of self-generated, individual drum patterns.

The challenge of transcription

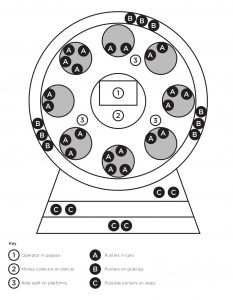

At first hearing, both Jones and Reich manifestly experienced some difficulty making sense of these elaborate superimpositions. Instead of recording the whole ensemble in the first place, Jones had started by asking each of the drummers to perform their motifs as a single line, working from simple repetitive to more complex patterns, and gradually combining several strands together so as to recreate an integrated composition. The way in which he did this was to get each performer to record the individual pattern allotted to his part onto a moving roll of paper that was electronically marked each time the musician tapped one of his metal pencils onto a sensitised plate. In an essay of 1972, Reich is very clear about the method involved:

As Dr Jones tapped out the bell pattern, an Ewe master drummer would tap out one of the drum parts, and both patterns would be recorded in accurate graph form on the moving paper. This was then transferred to conventional notation.12

The superimposition of the notated parts produced the full score, as reproduced in Figure 1 above. Jones’ method had been additive and analytic, building up the total sound picture from its barest elements. Here, from one of his recordings, is a snippet from one line of the Agbaza dance, later transcribed by Reich.13 The opening, for gong gong then sogo drum, may remind those of you who know of Reich’s Drumming; the rest is vividly reminiscent of his work Clapping Music of the following year.

In the ensemble that results from the combination of several such lines, all of the sonorities – drumming, clapping and singing – are superimposed. The first difference to note between Reich’s work and this African paradigm is that in the first three movements of Reich’s Drumming, the sonorities are separated out. The instruments featured in the first movement are tuned bongos; in the second movement these give way to marimbas, whose repeated patterns and tuning are imitated by monosyllables intoned by two sopranos; in the third these give way to glockenspiels, which, in turn, are imitated by the players whistling. In the fourth and final movement, all of these resources come together. In each movement, simple reiterated patterns are rendered more complex as additional players join in at short intervals from the basic pulse.

Reich’s Drumming and Africa

If you listen to the excerpts from Reich with Jones’ field recordings in mind, it is clear that, in one respect, Reich is adopting an equivalent approach. Drumming is a dramatic work, but it is also a cleanly analytical one, which derives at least some of its bearings from Jones’ research methods, or something very much like them. A player enters and sets up a basic pulse consisting of a twelve-quaver phrase, eleven of the twelve beats being rests. After repeating the phrase between three and six times, he fills in one of the rests, thus amplifying the pattern. After repeating the new pattern, he fills in a third quaver and then a fourth, before being joined by a second percussionist, who in turn is joined by a third. There is an intellectual fascination in the way in which the complexity of sound gradually builds up from these basic cells to form a whole rhythmic soundscape. Like Jones, Reich clearly wants us to experience each component element in isolation before we tackle the combined effect, to attend to the rhythms before we confront their combination. He is studying the rhythms as well as listening to them, with the result that parts of the work have the air of being a sort of demonstration of how sophisticated effects derive from simpler ones.

In assessing this effect, it is useful to bear in mind the principles that Reich had already set out two years before visiting Ghana in a personal manifesto written in San Francisco in 1968, Music as a Gradual Process, in which his preference for explicit musical procedures is very clear. ‘I am interested,’ he had written, ‘in perceptible processes. I want to be able to hear the process happening through the sounding music.’ And again, ‘To facilitate closely detailed listening as musical process should happen extremely gradually.’

The listener as performer

What is especially remarkable in both of these statements is the extent to which Reich places the listeners themselves in pole position. For Reich, the music happens in order to enable the listening, or rather a special sort of concentrated, analytical listening. For Reich, it seems, the music or musicking in which he is interested properly occurs only when it is listened to.

Theoretically, perhaps, a CD or record player playing a movement from Beethoven’s Eroica symphony in an empty room might be said to be delivering the music. Even with nobody around to attend to it, the symphonic movement might conceivable be said to have happened. The same could never be said of a CD player enunciating Drumming to an empty space.

Reich had always been quite happy with automatic and impersonal elements in a performance. He is even prepared to subordinate the contribution of live performers to the presence of tapes, just so long as the listener is conscious, animate and alert. As he himself put the matter in 1968:

As to whether a musical process is realised through live human performance or some electro-magnetic means is not finally the main issue. One of the most beautiful concerts I even heard consisted of four composers playing their tapes in a dark hall. (The tape is interesting when it’s an interesting tape.)

The operative verb in this declaration is ‘heard’: only a listener can find a tape interesting. (Is Beethoven interesting in himself?) Thus what advertises itself as a charter for an objective musical aesthetic comes to depend in the last resort on a kind of induced and structured subjectivity. If a listener happens to find Beethoven boring so, one might claim, the music itself is untouched. The same could never be claimed for Reich. A process can never be interesting in itself, but only if a listener finds it to be so. Listening, therefore, is a creative act and so, it might be said, is musical analysis.

Yet this analytical approach, in line with ethnomusicological theory and pedagogic practice, sets up a very different set of expectations from those underlying actual African performance. As Ali Momeni has observed in a study of Reich’s use of polyrhythms, ‘There is a disparity between the complexity of the rhythmic material in traditional African music and the single rhythmic cell present in Reich’.14 Just as other forms of minimalist music endeavour to build and recreate traditional harmonic and melodic effects from the ground up, educating the human ear to hear again and more appreciatively what over the centuries it has learned to take for granted, whether in melody or harmony, so Drumming strips down and rearticulates the basic materials out of which the tapestry of rhythmic polyphony is woven, in order to show us what goes into the mix. It is a sort of defamiliarisation technique which places strict demands on the audience, precisely by depriving them of the props and clichés that support lazy listening.

Listening, in our turn, we may be reminded of the fact that, prior to concentrating on music, Reich had been a philosophy student at Columbia, where he wrote a dissertation on Wittgenstein. Just as Wittgenstein had been interested in the procedures involved in various language games, so Reich had become fascinated by the workings of what you might call percussive sound games. Remember the second paragraph of Philosophical Investigations: ‘That philosophical notion of meaning is at home in a primitive idea of the way language functions. But one might instead say that it is the idea of a language more primitive than ours.’15 Just as Wittgenstein had endeavoured to dig down to the deepest roots of meaning, so Reich is attempting to uncover the most essential roots of rhythm. The problem is that, in Africa, the roots are far from being simple.

Reich’s debt to Africa

So what did Reich learn from Africa and what, just as importantly, did he resist? To appreciate both questions, it might be helpful to note that Reich seems to have arrived in Africa with a strong and individual sense of the sort of input that he did, or did not, require. So much was clear from our absorbing conversation, and it had already been spelled out for all to see in Music as a Gradual Process. First, he had already set certain conditions for composition as a determining process. He had also driven a gulf between his own approach and, on the one hand, the sort of improvisational music associated in America with the name of John Cage and, on the other hand, the serial technique cultivated in Europe by the Second Viennese School. His objections to both were founded on the fact that, while both deployed processes in their own sense of the term, in both instances the procedures involved were invisible or inaudible or, as he himself put it, ‘compositional ones that could not be heard when the music was played.’ Implicit in his critique is the further reservation that improvisation à la Cage is dependent on a sort of arbitrariness in which Reich was and is simply not interested. ‘One can’t improvise in a musical process,’ he had declared emphatically in 1968. ‘The concepts are mutually exclusive.’ Reich is interested in the inexorable working out of structured and audible ideas: the aleatoric has never been his thing.

More can be elicited about Reich’s predisposition immediately prior to his listening experiences in Accra from an interview with Michael Nyman, recorded in London in July 1970 while in transit to Ghana. Here Reich studiously avoids any reference to the now cliché term ‘minimalism’ (originally borrowed from art criticism), preferring his own term ‘pulse music’. Describing his earlier experiments with tape recorders, he explained how he had let tapes drift out of synchrony with one another to produce a kind of syncopation through delay. The resulting repetitions as the tapes disjointedly echoed one another had given rise to a technique of ‘phasing’ or what, in a beautifully modulated phrase, he called ‘a surrealist rondo with all kind of elements recurring’. The resulting work seemed to him to require, not simply new ways of composing and performing, but a fresh take on listening as well:

You listen to developmental music, and you can’t just stay with it, or you can’t stay with it once you’ve seen the way you can say with something else. I’m interested in a process where you can get on right at the beginning and literally rest on, uninterrupted, from beginning to end. Focusing on the musical process makes possible a shift in attention away from he and she and you and me, outward towards it.16

The required listening attitude has something in common with what nowadays is sometimes known as ‘trancing’.17 Eventually, though, Reich told Nyman he had come to feel ‘like a mad scientist trapped in a lab’. What he felt to be missing was the element of live performance: ‘I was aching to do some instrumental music.’ It was at this stage that he had decided to go to Ghana.

The very last intention Reich had in his mind, however, was to replicate the style and set-up of African music:

What I don’t want to do is to go and buy a bunch of exotic-looking drums and set up an Afrikanische Musik in New York City. In fact what I think is going to happen more and more is that composers will study non-western music seriously so that it will have a natural and organic influence on their music.18

Reich’s approach to African music was thus what, in a different context, the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins once described as a compulsion to ‘admire and do otherwise’.19 Through the activity of listening, Reich would convert this music into something completely his own.

Those pre-conditions granted, and given that a certain amount of controlled improvisation is essential to Ewe drum music, Reich’s debt to Africa is clear in at least two respects. Firstly, he convinced himself that a large-scale work made up of mostly percussive means could be built from quite elementary structures. Secondly, he seems to have copied the idea of a cuing technique, according to which one performer starts a new set of riffs, and invites the others to follow. According to Jones, this is an important element in Ewe ensembles, where the Master Drummer initiates each new stage of the proceedings. Reich was soon to rediscover a similar approach in Balinese Gamelan music, on which he was soon to write, and which Jones had been convinced had infiltrated African music at some point in the past.20

Africa, Reich and phasing

Apart from this, Reich seems to have assimilated lessons that he was already primed to learn. Much can be gleaned about the sound world of Drumming by examining the score. When he first prepared the work between the fall of 1970 and the following autumn, Reich jotted down his ideas in a series of notebooks, before teaching the piece to his fellow performers. Only after the premiere did he reduce the music to a pen and ink score, which circulated in manuscript for 40 years before Reich requested the Chicago-based composer Marc Mellits to rationalise the transcription.21 The result is a 79-page score set out in two-stave systems, with a uniform time signature of 3/2 or 6/4, and a key signature of five sharps. The apparent regularity serves as a guide or clue to what, in other respects, is quite a flexible mode of delivery. Since each pattern may be repeated between two and eight times (with permissible parameters being indicated in each case above the upper stave), the piece lasts between 55 and 75 minutes. Despite this, by Reich’s own admission, ‘there is one basic rhythmic pattern for all of Drumming which governs pitch, phase position and timbre’. The audible variations are caused by a scripted instruction that successive performers should delay slightly the beginning of each phrase. The phasing that results is quite in line with Reich’s practice in earlier works such as It’s Gonna Rain, in which two tapes are allowed to drift out of sync with one another and then to merge again, the difference being that in the new work these conditions are met by instructing the percussionists gradually to fall out of step. Listen to this snippet from the first movement of Drumming,22 where the phasing technique is easy to detect.

In the score there is a footnoted instruction to the effect that, in the first movement for example, the second drummer to enter should gradually accelerate his strokes so that, by the end of bar 20, he is a full crotchet ahead. Yet, after gradually parting company, in all movements the parts are designed eventually to realign and coincide. In Jones’ terminology, therefore, ‘synchrony’ is still ‘the norm’, since the rhythmic interest of the whole piece consists in listening to the parts as they sever company, and then join up again. Reich was to adopt an exaggerated form of the same procedure in Clapping Music where, as he explains, one performer remains fixed:

repeating the same basic pattern throughout, while the second moves abruptly, after a number of repeats, from unison to one beat ahead, and so on, until he is back in unison with the first performer. The basic difference between these sudden changes and the gradual changes of phase in other pieces is that, when phasing, one can hear the same pattern moving away from itself with the downbeats of both parts separating further and further apart, while the sudden changes create the sensation of a series of variations of two different patterns with their downbeats coinciding.23

Thus expounded, it is clear that what Reich achieves in all of these early works is a compromise between the synchronicity Jones had thought characteristic of the western tradition and the rhythmic polyphony and density he had discovered among the Ewe and other sub-Saharan African peoples. There is, however, in Africa no precise equivalent for the processes of addition, elimination and substitution (beats for rests, and vice versa) that Reich employs.

Ligeti and Reich

The very year in which Clapping Music was first performed, the Hungarian composer Gyorgy Ligeti (1923–2006) was in residence in Stanford, where he discovered an early recording of the work and an LP of Its gonna rain in the college library. The following year, he returned to Berlin, where he met Reich and heard a performance of Drumming. At the time he was writing Clocks and Clouds, featuring a wispy ostinato pattern akin to the humming of bees passed on from high cellos to flutes and thence to clarinets, Holst-like female voices and bells. It was a work avowedly ‘heavily influenced by Reich’. Soon he had embarked on an African adventure of his own as the echoing, hollaing polyphonic choral music of the Aka pygmies furnished him with a slightly schizophrenic listening experience caused by the repetition of its rhythmic cells and the asymmetry of the cells themselves.

At the time, Ligeti was in revolt against a two-fold tyranny: the Soviet totalitarianism still reigning supreme in his native Hungary and the artistic dictatorship of the Second Viennese School, more especially Anton Webern by whose work he had once been entranced. He was drastically in need of alternative modes of liberty. What seems to have attracted him to African music, just it had attracted Reich, was a combination of discipline with freedom. In the music of the Aka pygmies, for example, he had discovered a set of procedures that operated on two levels: the macro-level of its overall structure; and the micro-level occupied by individual performers free to devise their own rhythms, the separate patterns being reconciled at the level of the ensemble-performed piece.

In Ligeti’s own words:

Gradually through repeated listening I became aware of this music’s paradoxical nature: the patterns performed by the individual musicians are quite different from those that result from their combination. In fact the ensemble’s super-pattern is itself not played and exists only as an illusory outline, I also began to sense a strong inner tension between the relentlessness of the constant, never-changing pulse with the absolute symmetry of the formal architecture on the one hand and the asymmetrical internal divisions of the patterns on the other. What we can witness in this music in a wonderful combination of order and disorder which in turn merges together to form a sense of order at a higher level.24

Ligeti also suspected that these tendencies reflected some of the guiding principles of the Balkan folk music he had grown up listening to during his youth in Romania.

The legacy

There had thus been a sort of procession of influence: Ligeti listening to Reich listening to Africa, then listening to a different region of the continent with ears, in turn, trained by Reich. The response of both composers was partly dictated by their respective backgrounds: Reich by his earlier experiments with recorded tape, Ligeti by modernist practice overlying his own regional folkloric inheritance. If we pan out, I would suggest what we are observing is a kind of partition within modernism, stemming in Ligeti’s case from the two schools to which he had previously been exposed: the experimental Darmstadt School taking its cue from Shoenberg and the folkloric, regionally-based approach of his countrymen Bartok and Kodaly. It is no coincidence that by the 1980s western music gave the strong impression of looking forwards and backwards at the same time, so that by the century’s end the contemporary scene was dominated by this Janus-like stylistic face.

Nevertheless, it is clear that, just as Reich had taken what he wished from African music and then integrated it into his own practice, so Ligeti had taken what he wanted both from Reich and from Africa. Personally, he seems to have baulked at the idea of music as process. Wary as he seems to have been of all manner of imposed or necessary order, Ligeti was far more open to the idea of improvisation than was Reich. In a sense, both men were fleeing different varieties of orthodoxy associated with the mainstream avant-garde: Reich fleeing implicit invisible or inaudible structures, and Ligeti the inexorability of explicit form. Supposedly akin, both in their revolt against Darmstadt and all its works and in their shared attraction to the African paradigm, they ended as complementary opposites.

For both of them, however, the formal requirements of their art came to be fulfilled at the level of perception and reception as much as composition and performance. Structure is what is heard as much as – if not more than – what is intended.

Conclusion

What is undeniable is that in 1970 I had accidentally witnessed the stirring of a development that was to pay rich dividends in the musical history of the following half century, a period during which ‘world music’ came to be accepted as a field of inquiry and endeavour, and barriers between national musical traditions gradually broke down. The consequences of this mutually informed mode of listening, and the opening up of perspectives that ensued, has proved rewarding for all of us.

A further question arises as to how far the regional African musical traditions on which Reich and Ligeti drew were generically characteristic of the continent as a whole, though the thinking of both composers does seems to have been in step with Jones’ ideas as to a holistic African musical aesthetic, with rhythm as its bedrock. Finally, however, this question is far less important than might appear. In 1970 the Reich whom I met was in search, not of a local musical tradition as such, but of a formal indigeneity common to all cultures. The meeting between African and American that then occurred (with its side-occurrences in the music of Eastern Europe and Indonesia) has been but one facet of a far broader entente, with implications for listeners everywhere. As Reich himself emphatically stated in 1968, ‘All music is ethnic music.’

What the comparisons drawn together in this chapter further suggest is that, beginning in the late twentieth century, listening became an activity taking place at more than one level. Rules and departures from rules, pulse and the departure from pulse, perfection and incidental imperfection came to coincide in the listener’s ear. Impression superseded expression as the criterion of gainliness and value. The post-Romantic ideal of personal originality gave way before an aesthetic of communal appreciation. The listener assumed an active role, emancipated from passivity into collaboration.

Select bibliography

Fraser, Robert. West African Poetry: A Critical History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Glass, Philip. Words Without Music: A Memoir. London: Faber and Faber, 2015.

Jones, A. M. Studies in African Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Jones, A. M. Africa and Indonesia: The Evidence of the Xylophone and Other Musical and Cultural Factors. Leiden: Brill, 1964.

Reich, Steve. Writings on Music 1965–2000, edited with an introduction by Paul Hillier. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Reich, Steve. Drumming: For Percussion Ensemble. New York: Hendon Music; London: Boosey and Hawkes, 2011.

You must be logged in to post a comment.