Simon Brown is a Research Associate at the Royal College of Music working on the Listening Experience Database (LED) project, an Associate Lecturer with The Open University, and teaches Music Technology, Sound and Audio Theory at the Confetti Institute of Creative Technologies, which is part of Nottingham Trent University. He has recently submitted his PhD in Music at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire on Benjamin Britten’s performance annotations in his Mozart scores.

Abstract

The advent of social media is one of the iconoclastic events in communication. The content is opinionated and often (apparently) trivial and imitative, and is therefore regarded by many as ephemeral. But where people might once have written a letter or kept a private diary to record their response to a piece of music, many are now turning to social media to share their thoughts and opinions about what they have experienced in a more immediate and open forum.

Different social media platforms offer different types of evidence. Whilst some enable the listener to engage and interact with the music more directly (such as YouTube and SoundCloud), other platforms allow the user simply to leave their own response or to engage in a discussion with other listeners (such as on Twitter, Facebook or a discussion forum), but there is a multitude of other data that is often connected to these responses. One of the challenges is to identify source data (for example, based on specific hashtags or surrounding an event) and to build a collection of that data for further analysis.

This chapter will address how we might develop a methodology for the mining and analysis of social media as primary source material for responses to music. It will consider the impact these various social media platforms might have on the way the listening experience is being captured.

Introduction

One of the objectives of the Listening Experience Database (LED) project is to develop a methodology for the mining and analysis of social media as primary source material for responses to music. The challenges are to identify source data (for example, based on specific hashtags, music or events) and to build a collection of that data from sources such as blogs, Twitter and other social media platforms for further analysis. Developing a methodology will offer a means of understanding what is potentially a rich primary source for people’s listening experiences.

Before considering how listening experiences might be captured via such platforms, it is worth considering the factors to be considered in approaching this type of source material. Due to the large volume of material available from any given platform, the first consideration is to define what, precisely, is to be examined in order to provide a manageable focus for the study. For instance, we might decide to investigate comments or online conversations surrounding an artist, performer or composer; alternatively, we might focus on the musical work such as a song, album, or a specific performance or recording; or we could choose to focus on a particular venue, location, event or topic. All of these will inevitably yield different results and there will often be overlaps between many of them, but any one of them offers a starting point, at least, for this large dataset.

The challenge here is to filter these accounts sufficiently to avoid large amounts of ‘noise’ or semantically poor results, and to focus the search on accounts of experiences that support the research questions or topics being addressed. In this chapter my research questions are twofold: firstly, how might we mine and subsequently analyse evidence of people’s responses to live music on social media platforms; and secondly, how useful is social media data as a primary source for listening experiences? There is an incongruity here, in the sense that on the one hand the material is ‘born-digital’, 1[1] According to the website of the National Archives (see <a href="http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/manage-information/digital-records-transfer/what-are-born-digital-records">http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/manage-information/digital-records-transfer/what-are-born-digital-records</a>, accessed 3 November 2018), ‘born-digital records are records that have been natively created in digital format (rather than digitised from paper records)’. Examples include email, Word or Google documents and any text that is created in an online environment, such as blogs, Tweets or Facebook posts. making it easier to mine and analyse (particularly in comparison with older texts that might need to undergo a digitisation process); but on the other hand, its quality as evidence might be questioned, as it is often ephemeral, imitative and therefore regarded by some as trivial.

Microblogging

For the purpose of this chapter, I will focus on microblogs. According to Kaplan and Haenlein (2011), a microblog is commonly understood as being typically smaller than a traditional blog (in terms of both content and file size), ‘allow[ing] users to exchange small elements of content such as short sentences, individual images, or video links’. 2[2] See Kaplan and Haenlein, 2011, p. 106 It is worth considering the elements of a microblog, and in this chapter I shall focus on two of the most commonly used platforms, Twitter and Facebook, because of the wealth of data that can be extracted from them. 3[3] It should be noted that Twitter currently allows its data to be interrogated through an API (Application Programming Interface) in a way that Facebook does not, thus making the extraction and manipulation of the data for further analysis much easier. But many of the elements that make up a Tweet are consistent across other social media platforms.

In any given Tweet there will be several elements, or what I shall refer to as dimensions, including: the text, a URL to external content, mentions of other Twitter users or accounts using the ‘@’ symbol, and hashtags that are often used to exemplify the emotion or sentiment being expressed or to alert other members of the Twitter community to a particular topic or item of interest. These dimensions that form the content of a Tweet can (and usually do) occur in any order.

In 2017, Twitter increased the number of characters that are permitted in each Tweet from 140 to 280. For the purpose of analysing listening experiences, we might assume that focusing on the textual evidence within a microblog would yield the most interesting results, and that longer microblogs might be more informative, as more text might provide more information, but this is not necessarily the case. According to Twitter CEO, Jack Dorsey, ‘the expanded tweet length hasn’t actually changed the length of messages people are sending out—but it has led to more engagement’. 4[4] See Kastrenakes, ‘Twitter says people are tweeting more, but not longer, with 280-character limit’ in <em>The Verge</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.theverge.com/2018/2/8/16990308/twitter-280-character-tweet-length">https://www.theverge.com/2018/2/8/16990308/twitter-280-character-tweet-length</a>, accessed 10 September 2018. By ‘engagement’, Dorsey is presumably referring to the fact that, during the pilot at least, people who were able to Tweet with the longer character count found they received more Likes, Retweets and @mentions, but also gained more followers and spent more time on Twitter. Twitter published further evidence of this in a series of blog posts. 5[5] See Rosen, ‘Tweeting Made Easier’, <em>Twitter.com</em> [Online], <a href="https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/product/2017/tweetingmadeeasier.html">https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/product/2017/tweetingmadeeasier.html</a>, accessed 10 September 2018. Furthermore, due to the still relatively tight restrictions on Twitter’s character count, there is an argument that Tweets tend to be highly relevant, with a focused use of language.

Social media posts are often rich in personal listening accounts, but some are more informative than others. So how might we differentiate between them? How might we deal with spam or uninformative microblogs, where a person writes a string of words such as ‘love love love’, for instance, which will have an impact on the analysis of term frequency? There is evidence that the order in which the dimensions (as described above) are presented in a microblog matters and is connected with the informativeness or relevance. 6[6] See Perez and Joemon, 2015, p. 214. Whilst not strictly relevant to this study, it is possible to map the order of these dimensions as they occur from the start to the end of the Tweet (for instance: (1) text, (2) mention(s), (3) URL(s) and (4) hashtag(s), or any combination of these dimensions). Examining the order of these dimensions can assist in finding more informative microblogs during searches or when filtering the live stream. There is also an issue about repetitiveness in Tweets, particularly where people Retweet one another’s posts, which can affect the results and often ceases to be informative.

There are several platforms available that allow the interaction with Twitter data, including online tools that capture or monitor the live stream, and both free and paid-for services are now commonplace. Depending on the requirements, many offer a similar feature, that is, the ability to capture large portions of data given a specific search criterion.

Methodology for the mining of social media data

The Chorus Software Suite was developed by Dr Timothy Cribbin at the Department of Computer Science, Brunel University, and Professor Julie Barnett and Dr Phillip Brooker at the Department of Psychology, University of Bath. 7[7] For a detailed explanation of the software suite’s functionality, see the documentation provided by the Chorus Project Team, <a href="http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/support/">http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/support</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

Chorus Tweet-Catcher (Desktop Edition)

The Chorus package comprises two distinct programs. Firstly, Tweet-Catcher uses the Twitter API and allows users to mine the Twitter archive for relevant data in two distinct ways. According to Brooker, this can either be achieved by:

topical keywords appearing in Twitter conversations (i.e. semantically-driven data) or by identifying a network of Twitter users and following their daily ‘Twitter lives’ (i.e. user-driven data). 8[8] P. Brooker (2013) ‘Chorus: Twitter Data Capture and Visual Analytics for Social Science’, <em>Digital Methods as Mainstream Methodology</em> [Online], <a href="https://digitalmethodsnmi.wordpress.com/2013/04/11/chorus-twitter-data-capture-and-visual-analytics-for-social-science">https://digitalmethodsnmi.wordpress.com/2013/04/11/chorus-twitter-data-capture-and-visual-analytics-for-social-science</a><u>, </u>accessed 10 September 2018.

Depending on the search criteria, the results of this facility can provide large datasets that are rich in detail and include various metadata associated with either the Tweet or Twitter user.

Some of the metadata fields tend to be more populated than others (as highlighted in the User Manual by the Chorus Project Team, the GeoCordinates, for instance, are rarely disclosed by the Twitter user and are therefore usually blank, and the sentiment analysis score relies on the user of the software suite having Java installed, otherwise it will result in a score of zero). What is useful, for the purposes of collating and analysing listening experiences, is that it enables us to scale the dataset up or down. In other words, the software allows the user to ‘drill’ down into individual or small collections of microblogs over a very short time span, but also to see how these fit within the wider context of relevant Twitter conversations that surround them.

Chorus-TV (TweetVis)

The second component of the Chorus Suite is Chorus-TV (or TweetVis).

As Brooker suggests, the visual analytics approach is highly relevant to our aims, ‘enabling exploratory analysis of social media data in an intuitive and user-friendly fashion’. 9[9] P. Brooker (2013) ‘Chorus: Twitter Data Capture and Visual Analytics for Social Science’, <em>Digital Methods as Mainstream Methodology</em> [Online], <a href="https://digitalmethodsnmi.wordpress.com/2013/04/11/chorus-twitter-data-capture-and-visual-analytics-for-social-science/">https://digitalmethodsnmi.wordpress.com/2013/04/11/chorus-twitter-data-capture-and-visual-analytics-for-social-science/</a><u>, </u>accessed 10 September 2018. The results of the mining process feed back in to the methodology in an iterative way, allowing the user to explore what the data reveals, rather than approaching it with a specific research question in mind.

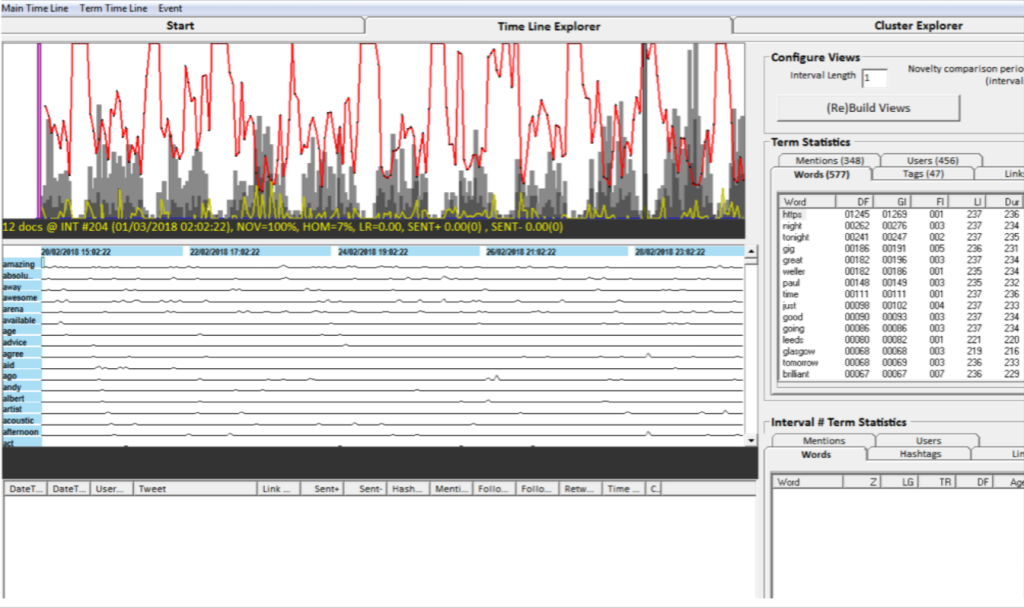

It is not necessary to go into a detailed explanation of what each facility of the software does 10[10] As mentioned above, interested readers might consult the online documentation available at: <a href="http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/support">http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/support</a>. but the Time-Line view essentially provides the high-level narrative of Twitter activity over the course of the study period. With reference to the figure above, the features that are of most interest here are as follows:

- The two grey bar-charts detail the tweet count (light grey) and tweet-with-link (URL) count (dark grey) for each interval.

- Each of the grey bars represents an hour’s worth of Twitter activity for the search term.

- Each interval (column) can be thought of as a ‘super-tweet’ wherein the value of each cell represents the proportion of tweets in that interval containing that term.

- The red and yellow line graphs represent novelty and homogeneity measures respectively, showing shifts in topic over time. Hence, each point on the red line is a measure of the dissimilarity in word frequency profile between that interval and other surrounding intervals. Similarly, each point on the yellow line is a measure of the similarity in word frequency profile between that interval and other surrounding intervals. 11[11] For reasons of both clarity and accuracy the following are taken verbatim from the Chorus TweetVis User Manual, <a href="http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/manuals/Chorus-TV_usermanual.pdf">http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/manuals/Chorus-TV_usermanual.pdf</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

The Term Statistics window on the right-hand side lists various term frequencies such as words, hashtags and usernames amongst others:

- DF refers to Document Frequency, or the number of Tweets in which the term appears.

- GI refers to Global Incidence, or the total number of times the term appears within the dataset.

- FI refers to First Interval, or the first interval in which the term appears.

- LI refers to Last Interval, or the last interval in which the term appears.

- Dur refers to Duration, or the difference between the first and last intervals in which the term appears.

Using the Chorus software to capture a dataset, which is focused on a Twitter username or hashtag (or both), the Time-Line view and Term Statistics window assist in the exploration of what the dataset reveals. This can include analysis of how the Twitter activity evolves over time, and/or word frequency and term statistics as outlined above. For the purpose of this chapter, the software enabled the study of how listeners responded on Twitter to a series of live performances by a well-established musician.

Case-study: paulwellerHQ

In order to demonstrate the application of the Chorus software, I shall use the English singer/songwriter and musician, Paul Weller (b. 1958), who first came to prominence with the punk rock/mod revival band, The Jam, between 1976 and 1982 and The Style Council between 1983 and 1989, before establishing his solo career in 1991. The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, Weller is an international artist with a fan-base of over 145,000 followers on Twitter and over 467,000 Likes on Facebook. This affords the opportunity to work with different scales of data should we wish, from the individual microblog to larger datasets of word lists using n-grams, and so on; but, also, it allows us to examine a sample of online primary source material for responses to the music of a specific musician, during a live event at a specific venue, across a short time frame. By the beginning of 2018, Weller was coming to the end of an extensive world tour that took in Australia, Japan, Canada and the United States, Europe and many cities throughout the UK. In order to provide a more detailed analysis of the evidence I shall focus on the last leg of this tour, with his performances in Leeds, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, Glasgow, and Nottingham in particular.

Firstly, as a point of comparison to the social media data that I shall later refer to, it is useful to consider the only published review of the concert on 27 February 2018, from the Nottingham Evening Post. It discusses Weller’s history, the set list, his persona on stage and some audience reaction, but overall it is not particularly enthusiastic:

As arena shows go, the roof remains on. But Weller holds attention throughout. Seldom addressing the crowd, he speaks most when signing-off to thank them for listening and for supporting him and his music for the past 40 years. 12[12] See A. Afford (2018) ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, <em>Nottingham Evening Post</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section">https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

It concludes that:

His career is actually more of an art installation. And he’s in his ‘unmade bed’ phase. By definition it’s not for everyone. But it remains interesting. Different to the point of challenging. And more than anything; king-sized. 13[13] See A. Afford (2018) ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, <em>Nottingham Evening Post</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section">https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

There are two reactions to this article in the comments section of the Evening Post website. The first reads:

Average at best shud [sic] stick to smaller venues to create a better atmosphere. Unlike noel gallagher who’s plying [sic] there soon who really blows the roof off. can’t wait. [sic] 14[14] See lindsey806 (2018) ‘Comments’ in Andy Afford’s ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, <em>Nottingham Evening Post</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section">https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

The mention of Noel Gallagher (the singer/songwriter from the band Oasis) is interesting as the comment comes a day after an increase in Twitter conversations following an attack on Weller by Noel’s brother, Liam Gallagher, as reported in the Evening Standard. 15[15] See E. Powell (2018) ‘What a k***’: Liam Gallagher slated by Paul Weller fans after scathing Twitter tirade’ in <em>Evening Standard</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.standard.co.uk/showbiz/celebrity-news/what-a-k-liam-gallagher-slated-by-paul-weller-fans-after-scathingtwitter-tirade-a3778886.html">https://www.standard.co.uk/showbiz/celebrity-news/what-a-k-liam-gallagher-slated-by-paul-weller-fans-after-scathingtwitter-tirade-a3778886.html</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

The controversy, amongst some of Weller’s Twitter fans at least, was that he would be supporting Noel Gallagher at the 2018 Downs Festival in Bristol. Weller fans took to Twitter to express their anger at Noel Gallagher being given the headline slot. In fact, the relationship between Weller and Noel Gallagher, as documented in a recent interview with NME, 16[16] See A. Trendell (2018) ‘Paul Weller on why he’s such a huge fan of Noel Gallagher’ in <em>NME</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.nme.com/news/music/paul-weller-hes-huge-fan-noel-gallagher-2250288">https://www.nme.com/news/music/paul-weller-hes-huge-fan-noel-gallagher-2250288</a>, accessed 10 September 2018. is one of mutual admiration and ongoing collaboration.

The second comment on the Evening Post article is more favourable:

Weller was on top form, problem is too many turn up just wanting to hear Jam songs and not interested in what Weller is doing at present. Go see Foxton if its Jam songs only you want to hear. For me after first seeing Weller in 83, last night was him sounding better than he ever has. 17[17] See Jimbob1969 (2018) ‘Comments’ in Andy Afford’s ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, <em>Nottingham Evening Post </em>[Online], <a href="https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section">https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section</a>, accessed 10 September 2018.

The mention of ‘Foxton’ relates to the bassist, Bruce Foxton, of The Jam, and it implies that there may have been a sense of negativity amongst some members of the audience wanting to hear more of Weller’s repertoire from his earlier years with The Jam. Further evidence of this will be found in the audience’s testimony.

Twitter data/comments

Using the Chorus software, a search was performed for Tweets from 20 February to 2 March 2018 that mention ‘paulwellerHQ’. This captured both the hashtag ‘#paulwellerHQ’ and Weller’s official Twitter account, ‘@paulwellerHQ’. This date range enables us to view the Twitter conversation during the days before and after this leg of the tour. It is interesting to capture listening experiences during the concert and to compare these in the days immediately before and after the event, so that we can understand how the content of the Tweets evolves. The search returned 4,705 results. This might sound like a substantial dataset but having removed the Retweets (2,160), which rarely contain anything of additional value in terms of listening experiences, it resulted in a dataset of 2,545 tweets. Of course, many of these were not related to the live concerts within the UK but were part of a wider community of Twitter users discussing Weller in more general terms. Returning briefly to the Term Statistics window in the figure above, it is apparent that some of the highest word frequencies amongst the dataset at a specific time include Weller’s name (as expected), the cities where he is currently performing, as well as adjectives such as ‘great’, ‘good’ and ‘brilliant’. The Term Statistics window also enables the data to be sorted by frequency of mentions, users, hashtags or links (URLs).

The concert at Nottingham Arena began at 19:30 with support by The Strypes and there is evidence that people took to Twitter to share the fact that they were at the event; we can see several comments where people were ‘waiting for the main man’ or ‘perfect Tuesday evening. [Nottingham] Motorpoint [Arena] to see @paulwellerHQ’. Others address their message directly to Weller, for example, ‘On our way to see you later. [sic] Also really looking forward to seeing @TheStrypes again too! Top night in prospect’.

From approximately 20:00 to 21:00 (during the start of Weller’s performance), there are no Tweets that relate specifically to the concert, with the frequency increasing as the night proceeds. This raises the question as to whether this is normal behaviour at a concert; as the artist begins their set, are people more inclined to focus on the performance (ignoring their smartphones), but turn their focus to recording their experience (or at the very least, sharing the fact that they are there, witnessing it live) as the gig progresses?

There is evidence of this if we look at the next interval of data from 21:00 to 22:00. At 21:15 there is the first recorded reaction, which simply reads ‘great show with @paulwellerHQ’ and the next at 21:41 reads ‘Paul’s on fire tonight, brilliant night in Nottingham’. But at 21:50 there is a noticeable change in the style of Tweets as people begin to include other hashtags or images. For instance, one listener writes ‘An evening with Paul Weller @chris[…] @paulwellerHQ @nottinghamarena #WellerLive’ and includes a photo of the tour programme. From the Twitter usernames, it is apparent that the listener is tagging their relative but also Weller’s Twitter account (despite the fact they have already mentioned him by name in the text). By including Weller’s Twitter username and the hashtag ‘#WellerLive’, which the artist often uses himself when discussing live shows over Twitter, they are both reaching out to the artist (presumably in the hope that Weller will at least see their response at some stage, or perhaps even respond directly to them, which incidentally, he is known to do quite frequently) but also highlighting to the rest of the Twitter community that they are in attendance. They also include the ‘@nottinghamarena’ Twitter account as a means to highlight where they are at that particular time, but also (presumably) to widen their reach to other followers or to the arena itself, which is likely to have many more followers than the individual currently has (at the time of writing, in March 2018, the listener has just 20 followers as opposed to the Arena’s 106,000).

As the concert draws to a close, there are a few more Tweets, such as at 22:29: ‘Awesome!! Nothing else to say!! @paulwellerHQ @BENGORDELIER Nottingham rocked!!! Thank you!!’, which includes a photo of the performers. Ben Gordelier is Weller’s drummer on the tour, and the fact that listeners can have this level of connectivity beyond Weller himself, with individual performers within the band is further testament to the immediacy (and, arguably, part of the attraction) of Twitter. Before the advent of social media, listeners at such events have rarely had this level of connectivity with the performers. Likewise, performers have rarely been in a position to receive such immediate and raw feedback on such a large scale.

Weller ends the concert with one of his best known hits from The Jam era, which is acknowledged in a Tweet at [22:53] ‘Town called Malice @paulwellerHQ @nottinghamarena #Class’ along with a video of the performance taken on their phone. The remaining Tweets from that evening all share the same positive sentiment and there is an increase in activity as people continue to record their experience immediately after the concert, including:

[23:09] @paulwellerHQ on top form in Notts. English Rose was my pick.

[23:21] What an amazing night watching the @paulwellerHQ band – got a wonderful programme with shit hot photographs and husband done some filming – thankyou very much

[23:30] Great night at @paulwellerHQ with the wifey

[23:50] Words cannot describe the performance by @paulwellerHQ at the @nottinghamarena tonight but phenomenal comes close! What a night! #PaulWeller #Notts #gigs #livemusic #singersongwriter

[23:54] Weller tonight in Nottingham #Legend @paulwellerHQ @HannahKCWeller [Hannah Weller is the musician’s wife]

[23:55] @paulwellerHQ just got home from Paul Weller Notts gig me and my son loved it thank you

What is striking about these is just how consistent the positive sentiment is. In comparison to the review from the Nottingham Evening Post critic (and the subsequent comment left by the Noel Gallagher fan, who is not entirely explicit as to whether they even attended the concert themselves or whether they are just offering their opinion), there is evidence that some of the audience appear to prefer Weller’s older (and therefore, presumably, more familiar) material. This is apparent from the mention of some of Weller’s more popular songs throughout the Tweets. But there does not appear to be any negative sentiment being expressed via these Tweets that replicate the critic’s suggestion that the ‘roof remain[ed] on’. 18[18] See A. Afford (2018) ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, <em>Nottingham Evening Post</em> [Online], <a href="https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section">https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section</a>, accessed 10 September 2018. Of course, these listening accounts might simply be evidence of a captive audience of Weller fans who were bound to be positive. But it might also suggest evidence that the professional critic’s view is not necessarily the same as the fan/listener experience.

Of further interest is the behavioural pattern that emerged from the Nottingham concert, which is replicated across the other three dates in Leeds, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne and Glasgow. The Twitter conversations begin with the anticipation of the show (as we might expect), but are then followed by silence (or very little Twitter activity) during the start of the performance, followed by an increase in Tweets and an expansion of the hashtags, usernames, posted photos and videos that are included in the Tweets. This trend continues into the next day although the inclusion of hashtags and relevant mentions of geographic Twitter accounts (such as @nottinghamarena) tends to trail off, which potentially highlights the importance of the time-sensitive content within the medium that people are using. Indeed, one of the attractions of posting a Tweet is that it allows users to divulge where they are at any given time (as reflected by the inclusion of geographic accounts or particular events with the use of a hashtag). In other words, it enables listeners to demonstrate the immediacy of their connection with the music – it is a way of declaring that they are actually there, listening to it live. But as time passes, the inclusion of such geographic accounts and hashtags is seemingly less relevant to users and is therefore often omitted. So how does this compare with experiences recorded on Facebook?

Facebook data/comments

One of the issues with collating microblogs of listening experiences from Facebook is that users can restrict who can see their posts. Depending on their privacy settings, this often means that only the people that they are connected with can see what they have posted. Therefore we should be cautious about drawing any firm conclusions from the data as we might only be relying on a small subset rather than the whole picture. That said, there are similarities to what was observed on Twitter in terms of the type of evidence being recorded throughout the different stages of the event.

As with Twitter, there are the usual posts before the performance written in anticipation of the event, where people are posting status updates describing how they are waiting for Weller to appear, or showing that they are at the concert by tagging the venue in their post. With regards to the Nottingham date, of the 33 posts that were visible, only five were posted during the concert, the majority (eighteen) were posted prior to the event, either late in the afternoon or immediately before (many mentioning having a meal or drinks prior to attending the concert), ten were posted either immediately after the gig had ended or the following day, and some of the discussions continued over the ensuing couple of days.

The five comments recorded on Facebook whilst the Nottingham concert took place offer little in terms of textual evidence. The first was posted at 20:34 and is a photograph of Weller and his band taken from within the crowd, accompanied by the brief statement ‘The arena Sir Paul Weller’ and the listener had tagged Weller in their post.

At 20:50 one listener is ‘feeling fabulous at Motorpoint Arena’ and states:

Here again this time for the legend that is Paul Weller xxx amazeballs.

As we saw with Twitter, the listener has tagged the venue here (commonly known as a ‘check-in’ on Facebook, as this records the user’s history of places they have frequented), which is further evidence of listeners demonstrating the immediacy of their connection with the music by acknowledging they were there. This is followed by another listener’s post at 20:52, observing ‘Motorpoint arena packed for paul weller’ (and again, the artist has been tagged). The next post tells us more about the listener’s levels of intoxication, rather than their listening experience. At 21:04 they write:

Me, kitchen Dave and Paul Weller [tagged] getting pissed!

In this post, the listener has chosen to comment on the Facebook event, which already has Weller and the venue tagged, but the listener has subsequently tagged Weller a second time within their text. And the final post at 21:42 is another photograph/selfie with their partner (presumably), and they simply tag Weller in it.

The comments that follow, after the concert has ended, appear to provide slightly more detail as people engage in more of a conversation. One listener writes immediately after the concert:

Well…Paul Weller [tagged] was epic!!

Once in a lifetime experience. Bloody smashed it lad

In response, one of his ‘friends’ comments the day after:

He’s hit n miss [sic] I think, sometimes he’s class and sometimes he looks like he can’t be arsed!

The original listener responds:

He was on it the other night though, you missed a good set mate. The new stuff not that fussed with but the classics.

This listener finishes their comment with the ‘OK Hand’ emoji. ![]()

And finally, posted the morning after the gig, another listener writes:

Blown away by Paul Weller [tagged] and his amazing musicians fabulous concert real talent![]()

![]()

In response to someone’s comment that:

You are never disappointed with a Weller concert hope he played some of your faves x

the original listener replies:

He did Graham but the whole concert was fantastic ![]()

As before, this listener relies on emojis to express their experience.

It is apparent that these conversations appear to be about expressing emotion and how the music made the listeners feel (hence their reliance on using emojis). They are not talking about the music in itself. Perhaps we could even venture to say that these people might lack the musical language to do that. But it is absolutely about the experience they have had and central to that is the sense that social media allows them to create a community of people around and including Weller himself, who they feel able to refer to familiarly as ‘lad’, as well as referring to each other as ‘mate’ and by first name (Graham) (even though they may never have met each other). It is a useful illustration of ‘ordinary listeners’ articulating their responses and validating each others’ responses in the process.

Conclusion

So what do these accounts of listening experiences from Twitter and Facebook reveal? The fact that some people shared their experience by posting on social media is evidence that the occasion was significant to them, or at least had some impact on them (whether the sentiment was positive or negative). It is difficult to say at this stage, without further analysis across a larger dataset, whether the textual evidence posted to Facebook is sufficient to provide us with any meaningful insights into the listening experiences; other than the listener during the Nottingham concert who described themselves as ‘feeling fabulous’, and the conversations that followed immediately after the concert and into the next day, they are all, perhaps surprisingly, even more succinct than many of the Twitter posts. But this does provide some circumstantial evidence that Tweets tend to be a relevant source, with a more focused use of language. There appeared to be a more consistent use of the dimensions within a Tweet than those found on Facebook; in addition to a more succinct usage of text, listeners would be more consistent in incorporating user names (@mentions), hashtags, URLs, photos and videos. It also reveals a couple of other characteristics of Facebook users: firstly, all of the listeners seem to be content with simply stating that they are attending the concert; and secondly, every listener (at this concert, at least) ensures they tag Weller’s Facebook page in their posts.

There is some evidence on both Twitter and Facebook that listeners wanted to hear more of Weller’s hits from The Jam era. Some would simply Tweet song titles to Weller’s account, which is curious – do they believe he might be checking his phone/Twitter account during the concert, or is it merely a means to provide the artist with feedback with the hope of influencing future performances? This was not replicated on Facebook but there is an underlying sentiment from at least a couple of listeners that they were keen to hear the ‘classics’ as opposed to Weller’s more recent material.

It proved much easier to capture this evidence from Twitter than Facebook. This is partly due to the restrictions enforced by Facebook that prevent the interrogation of their data without paying for the privilege, but also because the content of Facebook posts is not made readily available to the same extent as is currently the case with Twitter. Facebook users can also restrict their accounts via their security settings, which means that search results are often affected, as not all comments are visible. It is highly likely that more experiences were posted via Facebook than were visible to this study simply because users restricted their accounts so that only their network of ‘friends’ could see their posts. The fact that Twitter currently allows anyone to mine and subsequently analyse their data via an API means that it is a useful primary source for gathering people’s listening experiences. The Chorus Software Suite proved invaluable for this purpose. The functionality of the software means that further analysis is also possible on either term or word frequency. It enables the user to track how the Twitter conversation evolves over time, either by user or topic. The most useful features for the purpose of this study were: the ability to extract all of the Tweets that used a specific username or hashtag (in the first instance); the subsequent ordering of this data by date and time; and the ability to focus on small segments of the data in order to extract them and to compare them with the wider Twitter conversation. As stated, there are other tools available (both free and paid-for services) for this type of endeavour.

It would also be useful to compare the type of evidence captured on Facebook and Twitter with other social media platforms. For instance, YouTube affords users the ability to comment on videos of specific performances (and both published and unpublished versions of songs and/or concerts). This might allow for a more thorough investigation as the performance itself can be analysed to see how these comments compare to each other, as well as to any published reviews and the analyst’s own interpretation. Similarly, SoundCloud enables its users to leave a comment on precise points within a track that has been uploaded to their platform. This gives users the potential ability to leave more precise feedback (although a preliminary study has revealed that many of these comments are very short – usually just a couple of words – and therefore might be of limited use). Nevertheless, different social media platforms offer different perspectives on how listeners record their experiences.

Of course, this was just one small group of listeners that appeared to consist of mainly longstanding (and therefore presumably loyal) fans of Weller. Therefore, it is only representative of what is probably a similar demographic of people, whose usage of social media is likely to be quite different to that of other Twitter users (for instance, much younger generations with differing musical tastes). Therefore it would be interesting to see how these results compare across other Twitter users and different genres of music. The fact that the behaviour of Twitter users appears to be consistent across each of the four concerts in Leeds, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, Glasgow and Nottingham was of most significance. People followed a similar pattern of sharing their excitement in anticipation of the concert, followed by little to no activity on Twitter during the start of the concert, followed by an increase in Twitter activity and an expansion of the dimensions that continued the following day, albeit with a reduction in geographic or time-specific dimensions (such as including the event or venue). The reduction in posts being curated during the start of the concert was not replicated on Facebook, although the other behavioural patterns were. At the most simplistic level, this behaviour might suggest that listeners are most engaged with the performance during the start of the concert, with attention levels waning as time progresses, as evidenced by their decision to use their smartphones. Of course, this is not necessarily indicative of a negative response (indeed the evidence provided here suggests otherwise) but merely that listeners wish to record, capture and/or share their experience as the performance proceeds.

The fact that the content of microblogs can be opinionated and often (apparently) trivial and imitative, and is therefore regarded by many as ephemeral can be a reason why we might be reluctant to draw on it as a primary source material. However, if we look beyond the sentiment being expressed and use this in parallel with other forms of knowledge that can be extracted from the data, it can reveal useful insights into people’s behaviours and the way they record their listening experiences.

Select bibliography

Afford, A. ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, Nottingham Evening Post [Online], 2018, https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section, accessed 10 September 2018.

Brooker, P. ‘Chorus: Twitter Data Capture and Visual Analytics for Social Science’, Digital Methods as Mainstream Methodology [Online], 2013, https://digitalmethodsnmi.wordpress.com/2013/04/11/chorus-twitter-data-capture-and-visual-analytics-for-social-science, accessed 10 September 2018.

Brooker, P. ‘User Manuals’, The Chorus Project [Online], 2013, http://chorusanalytics.co.uk/support, accessed 10 September 2018.

Jimbob1969. ‘Comments’ in Andy Afford’s ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, Nottingham Evening Post [Online], 2018, https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section, accessed 10 September 2018.

Kastrenakes, J. ‘Twitter says people are tweeting more, but not longer, with 280-character limit’ in The Verge [Online], 2018, https://www.theverge.com/2018/2/8/16990308/twitter-280-character-tweet-length, accessed 10 September 2018.

lindsey806. ‘Comments’ in Andy Afford’s ‘Paul Weller is ‘interesting but not for everyone’ at Nottingham’s Motorpoint Arena – review and photos’, Nottingham Evening Post [Online], 2018, https://www.nottinghampost.com/whats-on/music-nightlife/paul-weller-interesting-not-everyone-1274359#comments-section, accessed 10 September 2018.

Perez, J. A. R. and Joemon, M. J. ‘On Microblog Dimensionality and Informativeness: Exploiting Microblogs’ Structure and Dimensions for Ad-Hoc Retrieval’ in Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on The Theory of Information Retrieval, 2015, DOI: doi>10.1145/2808194.2809466 pp. 211-220, accessed 10 September 2018.

Powell, E. ‘What a k***’: Liam Gallagher slated by Paul Weller fans after scathing Twitter tirade’ in Evening Standard [Online], 2018, https://www.standard.co.uk/showbiz/celebrity-news/what-a-k-liam-gallagher-slated-by-paul-weller-fans-after-scathingtwitter-tirade-a3778886.html, accessed 10 September 2018.

Rosen, A. ‘Tweeting Made Easier’, Twitter.com [Online], 2017, https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/product/2017/tweetingmadeeasier.html, accessed 10 September 2018.

The National Archives. Born-digital records and metadata [Online], 2018, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/manage-information/digital-records-transfer/what-are-born-digital-records, accessed 3 November 2018.

Trendell, A. ‘Paul Weller on why he’s such a huge fan of Noel Gallagher’ in NME [Online], 2018, https://www.nme.com/news/music/paul-weller-hes-huge-fan-noel-gallagher-2250288, accessed 10 September 2018.

Please leave a comment or share via social media by clicking on the icons.

View the online publication details 19[19] <em>The Experience of Listening to Music: Methodologies, Identities, Histories</em> has been Open Access funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC), grant AH/J013986/1, https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019 The collection has been peer reviewed, edited by David Rowland and Helen Barlow, and subsequently prepared for online publication by the Knowledge Media Institute (KMi) of The Open University. Published by: The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA. Copyright © The Open University. First published: July 2019. ISBN: 9781473028647. PDFs displaying some of the content from the online collection are available from <a href="https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019/getting-the-best-from-this-website/">https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019/getting-the-best-from-this-website/</a> You can experience the online publication as it was originally designed at <a href="https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019">https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019</a> View copyright information relating to the publication here: <a href="https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019/copyright">https://ledbooks.org/proceedings2019/copyright</a>

Download: #areyoulistening: mining social media to collate people’s listening experiences